Here’s how an overdose shuts down your body.

U.S. deaths from opioid overdoses are mounting with breathtaking speed. These powerful drugs — including heroin, morphine and fentanyl — can relieve pain and evoke intense feelings of pleasure.

But the same drugs, whether prescribed by a doctor or bought on the street, can quickly turn deadly by simultaneously messing with crucial systems in the body.

Among the many rapid effects that opioids have on the body, one is particularly lethal: Breathing is restricted.

“Opioids kill people by slowing the rate of breathing and the depth of breathing,” says medical toxicologist and emergency physician Andrew Stolbach of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Breathing delivers fresh oxygen to the body’s cells and eliminates carbon dioxide. Opioids can interfere with that life-sustaining process in multiple, dangerous ways.

Here’s how opioids kill.

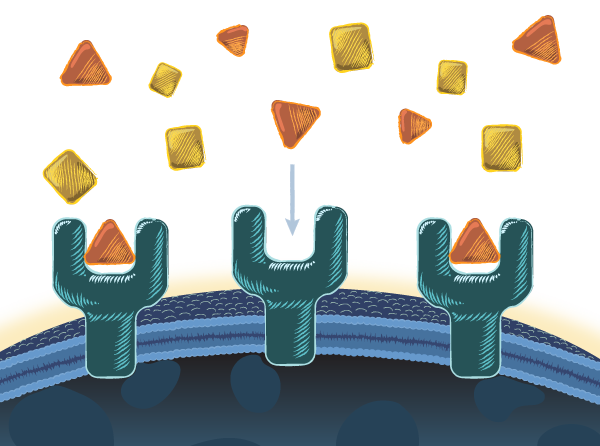

In the brain stem, regions called the medulla and the pons control the depth and rate of breathing. Both are loaded with opioid receptors — proteins that sit on the surface of cells and grab onto opioids.

Upon activating, the receptors change the behavior of cells in ways that can slow or even stop breathing.

Opioid receptors have also been found in areas of the brain that regulate voluntary breathing — when you feel the need to take in a deep swallow of air, you do it.

So, opioids might depress breathing by working directly on areas of the brain outside the brain stem.

The brain stem and certain other parts of the brain are particularly rich in the receptors that attach to opioids. When the connection is made between opioids and these receptors, the cell reacts. The effects vary depending on the cell’s location. Opioid receptors are found in tissues, organs and muscles throughout the body.

Sensing small increases in CO2, the carotid body, a small cluster of cells in the neck, spurs big increases in breathing to remove excess CO2 and keep a person out of trouble.

But opioids dampen these sensors and silence the body’s CO2 warning system. Emergency signals to increase breathing go unsent.

One of the telltale signs of opioid overdose is frothy fluid around the nose and mouth and fluid in the lungs, called pulmonary edema.

It’s not clear how opioids trigger this, but filled with fluid, the lungs can’t oxygenate blood very well, and a person may slip further into respiratory trouble.

A fast-acting injection of the opioid fentanyl can cause the diaphragm and other muscles in the chest to seize up, leading to what’s called “wooden chest syndrome” (SN: 9/3/16, p. 14).

Opioids also affect other parts of the body.

Opioid receptors exist throughout the body, so the drugs can cause plenty of nonlethal problems, some of which can signal to medical staff that a person has recently taken opioids. A dose of opioids can…

Suppress the throat’s gag reflex. If sedated or groggy, a person might be more likely to aspirate vomit and choke, particularly when alcohol and other sedatives are used.

Cause a slight drop in blood pressure or trigger an abnormal heart rhythm.

Dilate blood vessels in the arms and legs.

Shrink the pupils to pinpoints.

Slow digestion and cause constipation and may even affect the microbes that dwell in the gut.

Blocking opioids’ dangerous effects

To treat an opioid overdose, doctors use drugs such as naloxone, often sold as Narcan. The potent opioid blocker latches onto empty opioid receptors, preventing other opioids from triggering the cell to take actions that can shut down breathing or freeze muscles.

Usually injected or inhaled, naloxone starts working in minutes and, in many cases, can reverse the overdose.

Some medical treatments for opioid addiction also target opioid receptors. Drugs including buprenorphine are known as partial agonists, which activate opioid receptors to a lesser extent than heroin and other agonists. The middling effect staves off withdrawal and keeps people from turning to the more dangerous heroin or fentanyl. But if used incorrectly, buprenorphine and other opioid-based treatments can also kill.

Deadly trends

Roughly 64,000 U.S. residents died from a drug overdose in 2016, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioids were involved in the vast majority of those deaths.

From 2015 to 2016, the number of deaths from lab-made opioids, including fentanyl and chemical kin such as carfentanil (used to tranquilize large animals), more than doubled in the United States.

Overdose deaths in 2017 are still being counted, but data through July suggest that it was also a bad year.

Hidden in these national statistics are stories of individual people. Researchers are still struggling to understand how lifestyle factors, such as prior drug use and stress, as well as genetics and other risk factors, might make people more likely to overdose on these deadly drugs.

Citations

K.T.S. Pattinson. Opioids and the control of respiration. British Journal of Anaesthesia. Vol. 100, June 2008, p. 747. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen094.

F.B. Ahmad et al. Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics, 2018.

H. Hedegaard, M. Warner and A.M. Minino. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2016. NCHS Data Brief. No. 294. December 2017.

M. Kang et al. The effect of gut microbiome on tolerance to morphine mediated antinociception in mice. Scientific Reports. February 17, 2017. doi: 10.1038/srep42658.

Overdose death rates. National Institute on Drug Abuse, September 2017.

Further reading

L. Hamers. The opioid epidemic spurs a search for new, safer painkillers. Science News. Vol. 191, June 10, 2017, p. 22.

L. Sanders. Fentanyl's death toll is rising. Science News. Vol. 190, September 3, 2016, p. 14.

Credits

Story: Laura Sanders

Illustrations: Nicolle Rager Fuller

Editor: Cori Vanchieri

Digital director: Kate Travis

Design director: Erin Otwell

Assistant art director: Chang Won Chang

UX designer/developer: Alison Buki