Conversations with Maya: Paul Modrich

Paul Modrich, James B. Duke Professor of Biochemistry, Duke University Medical Center

Maya Ajmera, President & CEO of the Society for Science and Publisher of Science News, chatted with Paul Modrich, James B. Duke Professor of Biochemistry at Duke University Medical Center, ahead of his retirement. Modrich won the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 2015 and participated in the 1964 Science Talent Search and the 1964 National Science Fair, today called the International Science and Engineering Fair.

Paul, you are an alum of both the 1964 Science Talent Search and the National Science Fair. How did those competitions impact your life?

As a teenager, I was interested in the possibility of a career in science, but I really had no idea how realistic that was. I think it’s fair to say that the opportunity to attend the National Science Fair and compete in the Science Talent Search were truly great opportunities for me. Those competitions suggested that a career in science might actually be a real possibility for me. I also think the competitions had a lot to do with my getting into MIT as an undergraduate.

Your beginnings in science may seem atypical to some. You grew up in a small town in New Mexico where there was only one biology teacher, your dad. What inspired your interest in science?

I was always fascinated by science as a boy. When you grow up in a rural area, nature is right there. It’s right in your face and for me, often quite moving. I still feel that same thing every time I return to New Mexico.

Who were some of your early mentors and how did they inspire or influence your career in science?

My parents, of course, consistently encouraged my curiosity about science. My father was a great biology teacher. He influenced not only me, but a number of others from my high school who went on to pursue careers in biology or medicine, which is unusual for a small town like mine.

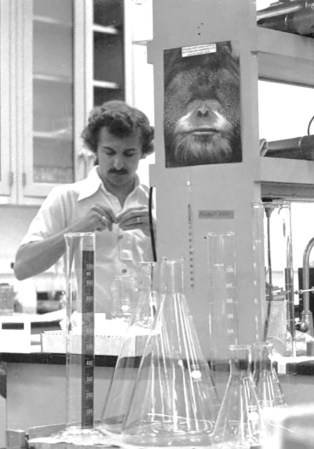

Salvador Luria, one of the fathers of molecular biology, was my academic adviser at MIT. He was an excellent teacher who took great interest in his advisees. I’m convinced he had a lot to do with getting me into Stanford University’s graduate school. I had the privilege of doing my graduate work in Bob Lehman’s laboratory, where I studied an enzyme called DNA ligase that can seal a break in a DNA strand. Then I did my postdoc with Charles Richardson at Harvard Medical School, working on DNA replication. Bob and Charles are both among the world’s greatest DNA biochemists, but they’re also wonderful people. I learned how to do science working in their laboratories, where they allowed me a great deal of freedom in my choice of experimental pursuits. I regard working with them as highlights of my career.

You’ve described yourself as an experimentalist. What do you mean by this and how does it characterize your approach to research?

When I write a grant application, I frame the problem in terms of: This is what we know, these are the unanswered questions and this is how we’ll address those questions experimentally. A well-designed experiment can give you the truth. The physicist Richard Feynman wrote, “The ultimate test of knowledge is experiment. Experiment is the sole judge of scientific ‘truth.’ ”

You received the Nobel prize in chemistry in 2015 for your discoveries concerning the mechanisms of DNA repair. What was it like to get the call?

I never actually got the call. My wife and I were at our cabin in New Hampshire, and when we returned to North Carolina, our answering machine was full of calls from Stockholm. I actually learned about the honor from a former postdoc, who left a voicemail on my cell phone. It was a shock but also a wonderful surprise.

How would you describe the impact of your work on human health as well as advancing your field?

There are multiple pathways of DNA repair. We worked in an area called mismatch repair, and what mismatch repair does is correct rare errors that occur when a chromosome is copied. During DNA replication, the two strands of the DNA helix separate, and two new strands are synthesized using the separated parental strands as templates. The enzymes responsible for synthesis of these new strands are extremely accurate, typically making about one mistake for every million to 10 million bases copied. But cells have a lot of DNA. A human cell contains 6 billion base pairs, so even with one error in a million or one error in 10 million, you still get a lot of mistakes. Those mistakes, which otherwise would become mutations, are corrected by mismatch repair.

We established basic features of how this pathway works, initially in the bacterium E. coli and then in human cells. During our work on the human pathway, we demonstrated that it is defective in cancer cells from patients with Lynch syndrome, one of the most common forms of hereditary cancer. We also showed that the pathway is defective in certain sporadic cancers where one of the mismatch repair genes turns out to be epigenetically silenced.

A few years ago, you met with then Vice President Joe Biden as part of the Cancer Moonshot initiative. Are there policies or institutional supports you think would be particularly impactful in supporting researchers addressing large interdisciplinary challenges?

That is something of great interest. The National Institutes of Health, as you know, is the primary funder of biomedical science in this country and has a history of promoting large interdisciplinary research, especially in areas that target certain diseases, like cancer. That is certainly appropriate given NIH’s health-related focus, but I would like to speak to an alternate view: that the establishment of large, targeted programs must not occur at the expense of smaller basic science research projects initiated by individual investigators. Such research is important because much of what we know about the fundamental nature of cell and organ function have been derived from the pursuit of basic science questions in a small science format. Many of the most valuable technologies available to modern biomedical science — genome sequencing and the polymerase chain reaction for example — emerged from basic science discoveries made by individual investigators.

What advice do you have for young people just starting college or their careers?

For college students who are considering the possibility of a research career, a good way to determine if this is the kind of life for you is to find a laboratory where you might work 10 to 15 hours a week, and maybe over the summer as well. For someone who is beginning their career as an academic scientist, I would suggest choosing a problem that they regard as important but highly undeveloped and then pursue that problem in great depth. Avoid the temptation to jump around in ways that contribute only incrementally to problem areas that have been largely developed by others.

What books inspired you when you were young?

When I was a teenager, I was very fond of science fiction. In college, I read every book that John Steinbeck wrote. He’s still my favorite author.

There are so many challenges in the world today. What keeps you up at night?

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, of course, and the pandemic, although hopefully that’s abating. I’m also troubled by the recent balkanization of politics in the United States and the apparent disappearance of compromise as a political tool in our Congress.

I also worry about the environmental, social and economic impacts of global warming and am particularly concerned that an underlying primary problem is not being publicly discussed at all. We talk about carbon emissions, but that’s not the only problem. Another problem is the size of the global population.

Although there’s not uniform agreement, people like former Harvard University sociobiologist Edward O. Wilson have estimated that Earth’s carrying capacity is about 9 billion people. We’re almost there. I personally regard this as a very serious problem, but it’s one that appears to be on the mind of only a few scientists, when in fact it should be of concern to us all, especially policy makers.