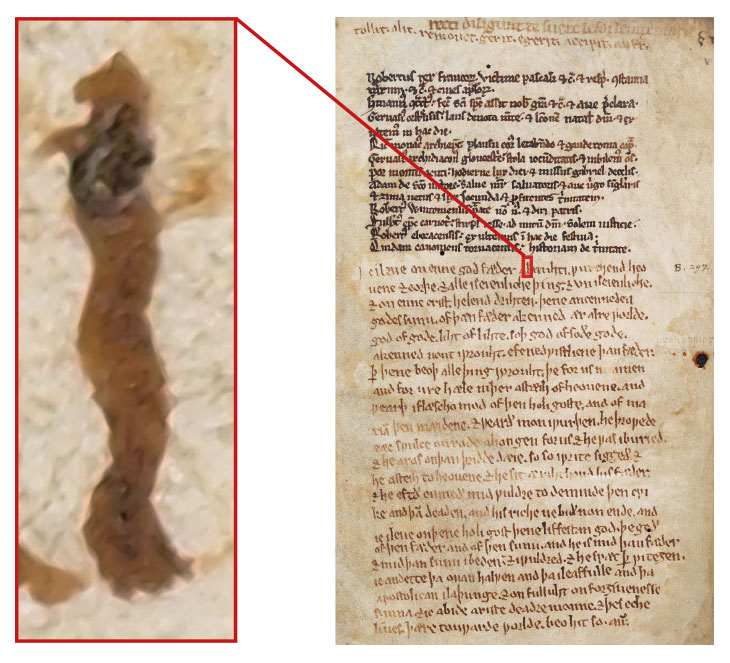

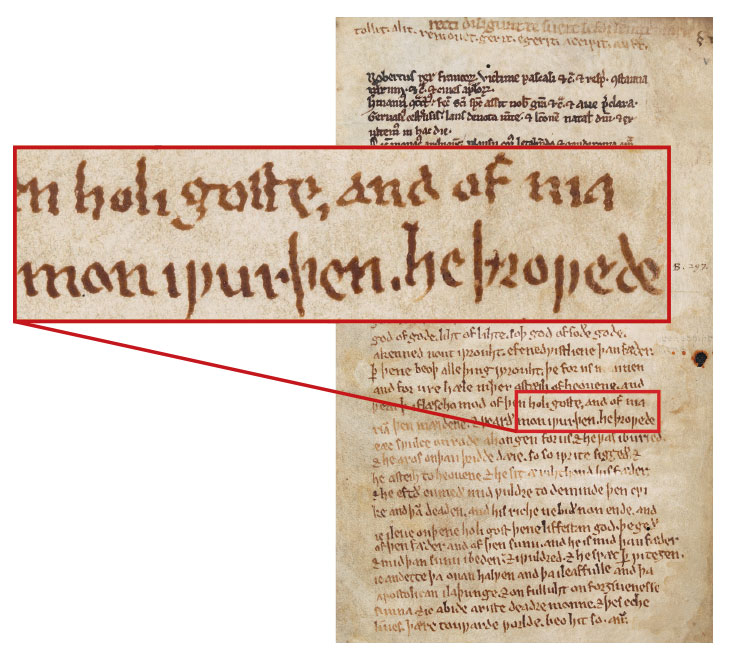

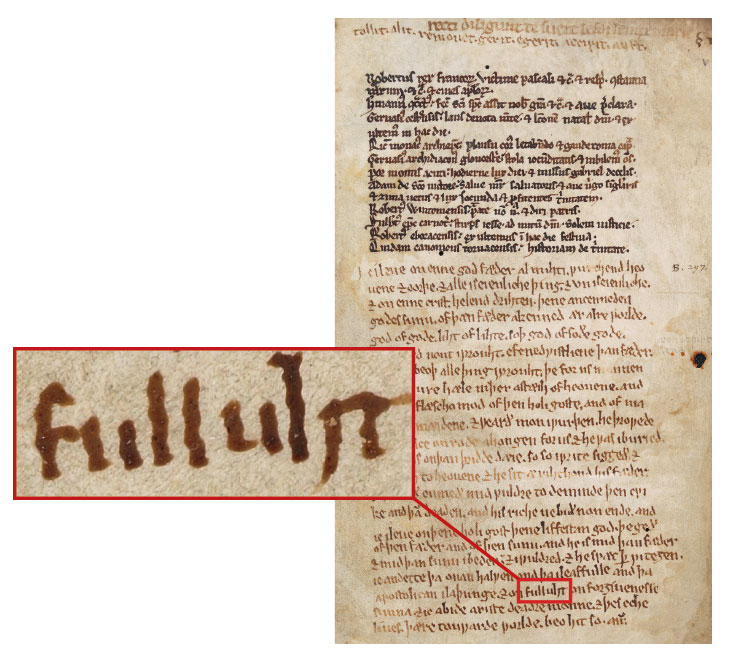

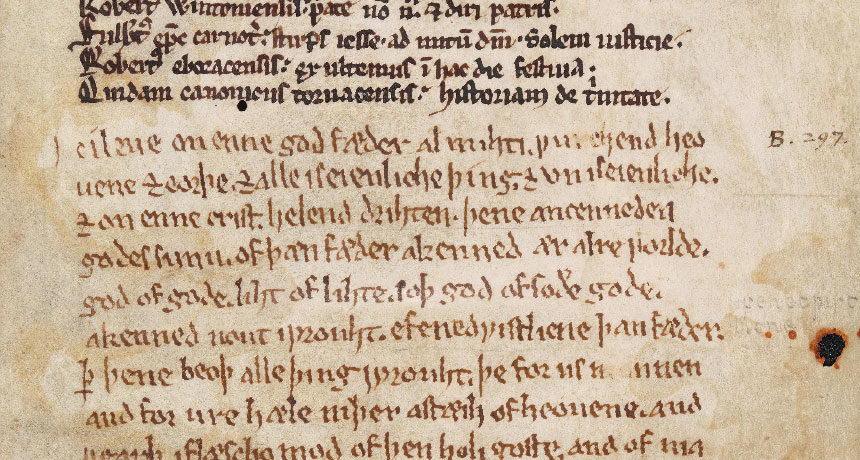

Neurological condition probably caused medieval scribe’s shaky handwriting

Manuscript analysis suggests 13th century writer had essential tremor

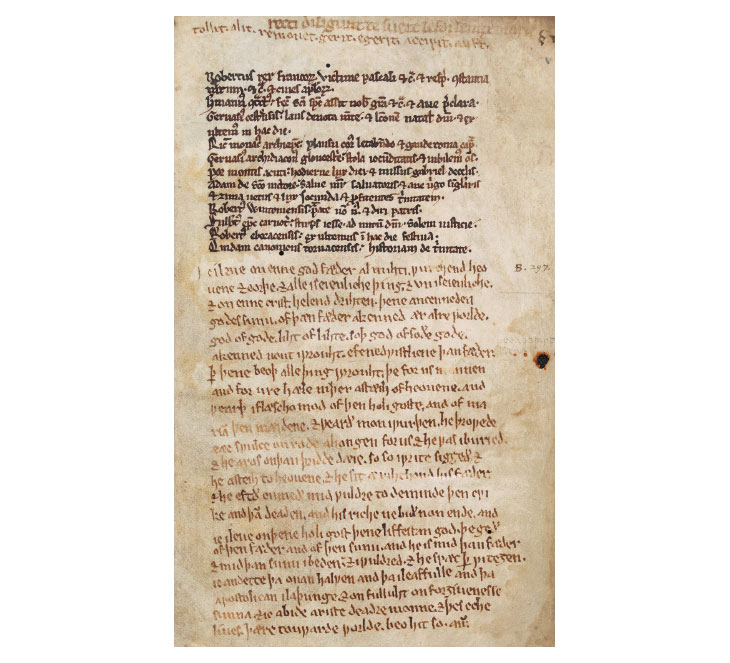

SHAKY SCRIPT An anonymous 13th century scribe with an unsteady hand wrote manuscripts including this early Middle English version of the Nicene Creed. Scientists now suspect the writer had a neurological condition called essential tremor.

Bodleian Library/Univ. of Oxford 2015, Ms. Junius 121, Fol. Vi Recto