To catch a cheat

Researchers know when urine has been tainted

Drano, All laundry detergent and Arm & Hammer baking soda have become drug-addicted job applicants’ last resorts to pass urine screenings. But researchers performing lab tests are one step ahead.

Legislation allowing workplace drug testing began in 1986. During the late 1980s, 13 percent of the tests came back positive. Now, less than 4 percent show a positive result, in part because 13 states now ban the sale and distribution of drug test altering chemicals, said Amitava Dasgupta during a press conference July 28 at the annual meeting of the American Association for Clinical Chemistry.

“It is a game of cat and mouse,” said Dasgupta, a pathologist at the University of Texas Medical School at Houston. “As more companies try to achieve drug-free work environments, more people attempt to beat drug tests with additives, flushing agents and drug-free urine purchased on an increasing number of websites.” Toxicologists respond by creating new screenings to catch the cheaters, he said.

Dasgupta demonstrated how prospective employees attempt to cheat on drug tests using additives brought from home or even with expensive ones purchased on the Internet. He also showed the tests laboratory scientists use to catch these kinds of potential cheaters.

“People who abuse drugs need work,” he said. “They need money to pay for their habit, and they do anything to cheat on drug tests.”

The altering chemicals, called adulterants, disrupt the antibodies toxicologists use to identify the presence of an illicit drug in urine. A person might add a household bleach or cleanser such as Drano to cover the presence of drug use. But products like Drano change the color of the sample and also raise the pH, the measure of acidity or alkalinity. The standard pH of urine with no added substances is between 4 and 8, Dasgupta said. Drano makes a sample climb to 14, the most basic reading on the pH scale.

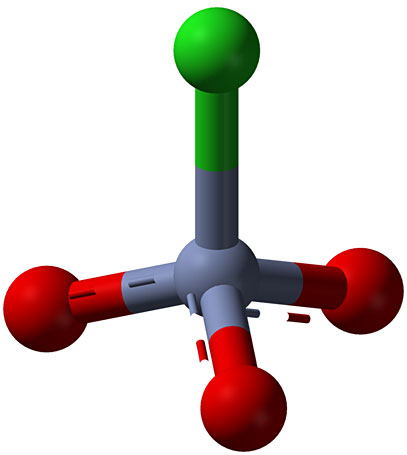

For more sophisticated approaches to cheating, drug addicts purchase fake urine or complex chemical compounds to get a negative test. These compounds, pyridinium chlorochromate and potassium nitrite, destroy the drug molecules, specifically those indicative of marijuana, Dasgupta said. But, he countered, toxicologists have simple “spot tests” that use hydrogen peroxide and other common chemicals to test for even the most complex adulterants. If the sample is tainted, it is considered invalid. The drug test is incomplete, and the prospective employee is not hired, he said.

Dasgupta said while a federal law banning the fabrication and distribution of complex adulterants should be created, nothing would prevent the companies creating the compounds from moving overseas and shipping their products back to the United States.

But, he continued, no matter the cost, keeping workplaces drug-free is important because clean environments prevent accidents and also improve productivity. The American Council for Drug Education reports that drug abusers are 33 percent less productive and 10 times as likely to miss work than employees who are sober and do not use drugs. Drug abusers are also almost four times more likely to be involved in on-the-job accidents and five times more likely to file workers compensation claims for such accidents.

“This is a very important public safety issue,” Dasgupta noted.