Genes & Cells

Microscopic murderers caught dealing poison, fighting aging with hibernation and more in this week's news

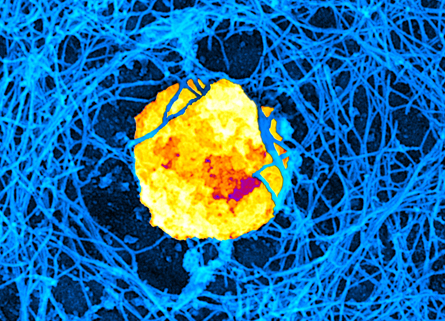

Catching a natural killer in the act

Microscopic images of disease-fighting cells may one day help treat

immune deficiency disorders. Jordan Orange of the Children’s Hospital

of Philadelphia and colleagues used a superpowerful new microscope to

watch how immune cells called natural killer cells feed a poison pill

called a lytic granule to tumors or virus-infected cells. Scientists

used to think a big hole in the middle of a dense mesh of

spaghetti-like molecules called F-actin let granules stream out of the

natural killer cell. But the new study, published online September 13

in PLoS Biology, shows that the meshwork parts just enough to

let single lytic granules pass, with F-actin helping squeeze the

granule through. People with immune deficiency disorders may have

defects that prevent lytic granules from exiting the natural killer

cell. —Tina Hesman Saey

Host genes determine how bad H5N1 infection gets

The H5N1 avian influenza virus may get its killing power from its host. It hasn’t been clear whether humans die from having lots of viruses in their lungs or from making too many inflammation-producing chemicals. Now researchers at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tenn., and Roche Pharmaceuticals in Palo Alto, Calif., have evidence from studies in mice that the victim’s own genetic makeup determines how well the virus grows in the lungs. Genetically susceptible mouse strains had more viruses in their lungs than resistant strains, the team reports online September 6 in mBio. More viruses lead to more inflammation, too. —Tina Hesman Saey

Hibernation reverses aging

Hibernating hamsters turn back the clock on at least one sign of aging. Djungarian hamsters kept in the cold go into torpor (a type of short-term hibernation) each day. During this torpor, telomeres, the protective end caps on chromosomes, grow more than those of hamsters dozing in warmth, researchers from the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna report online September 14 in Biology Letters. Telomere length is one measure of aging. Longer telomeres weren’t due to slower metabolism or decreased food intake, the researchers say. Instead, something else about torpor slows or reverses the aging process. —Tina Hesman Saey

Immune cells link brain and immune system

Scientists have found a surprising new connection between the brain and the immune system. In two papers, both published online September 15 in Science, researchers show that important immune cells called T cells make the link. In one study, Kevin Tracey of the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in Manhasset, N.Y., and international colleagues show that the vagus nerve sends signals to a subset of T cells that produce the chemical acetylcholine. Those T cells then help calm inflammation. And researchers at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada, show that strokes suppress the action of immune cells in the liver and spleen of mice, leading to weakened immune reactions. —Tina Hesman Saey