View video footage of the sun’s activity at the bottom of this article.

There’s plenty new on the sun, both inside and out, a recently launched solar observatory has discovered.

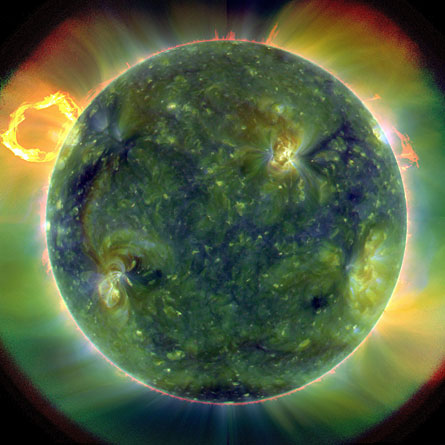

After staring at the sun for only a few weeks, NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory has already recorded the interplay between a small sunspot on the solar surface and disturbances high in the sun’s outer atmosphere. It has also made the first high-definition recording of a solar eruption over a broad range of ultraviolet wavelengths.

An ultimate goal of the observatory is to better predict and understand the origin of giant eruptions, called coronal mass ejections, in the sun’s outer atmosphere. When directed at Earth, these billion-ton parcels of magnetized gas can disrupt electrical power grids and satellites.

Unlike several other solar observatories that are orbiting Earth, Solar Dynamics looks at the full disk of the sun in high resolution, taking images as often as every 1.25 seconds over a wide spectrum of wavelengths. These include pictures tracking the tangle of magnetic fields that drive solar activity and the roiling motion of gases that reveal the pattern of acoustic waves reverberating beneath the solar surface.

On April 21 NASA released some of the first images recorded by the craft. The observatory was launched February 11 and is expected to collect data for five years.

“The idea is to observe all of the sun all of the time, so you can see what happened before an important event occurs” says Philip Scherrer of Stanford University, lead scientist on the observatory’s helioseismic and magnetic imager. “We haven’t been able to do that before.”

“You can’t just look at one part of the sun” if you want to understand the forces that drive solar eruptions, says Dean Pesnell, project scientist for the observatory at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

On March 30 the observatory captured one of those eruptions as it lifted off the sun’s visible surface. Images reveal that the disturbance contains a twist in its magnetic field, a feature that some solar physicists believe is necessary to initiate a solar eruption.

Observations of the sun’s magnetic field before the eruption should settle the ongoing debate about whether the twist is necessary to initiate the eruption, says solar physicist Spiro Antiochos of NASA–Goddard.

A key advance, he adds, is the observatory’s ability to simultaneously observe both the magnetic field at the sun’s visible surface and the detailed structure of its outer atmosphere, or corona, at several temperatures.

Images of the corona and the solar surface taken April 8 show disturbances in the corona around the time that a small, roughly Earth-sized sunspot disappeared. It’s likely that the magnetic field from the sunspot drove the activity in the corona, scientists say.

“It’s surprising that something so insubstantial, just a small pore,” could be the culprit, says Alan Title of Lockheed Martin’s Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory in Palo Alto, Calif., and lead scientist for the observatory’s atmospheric imaging assembly.

“After building this craft for eight years and finally getting it into the sky,” says Pesnell, “it’s just performing beautifully.”

This movie shows two events captured by the Solar Dynamics Observatory. The first is a prominence that erupted March 30, followed by a solar flare that was released by the sun April 8.

Credit: NASA, AIA/SDO