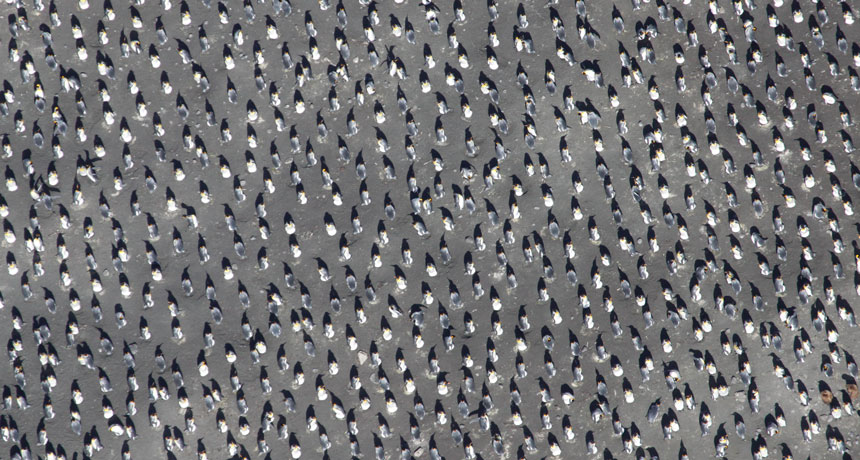

In a colony, king penguins behave like molecules in a 2-D liquid

Aerial images help show how members of this species behave in a group

PERSONAL SPACE Positions of king penguins in a breeding colony resemble molecules in a 2-D liquid, a new study finds.

French Polar Institute Paul-Émile Victor