‘Big Chicken’ chronicles the public health dangers of using antibiotics in farming

Efforts to raise bigger birds unwittingly spawned drug resistance in bacteria

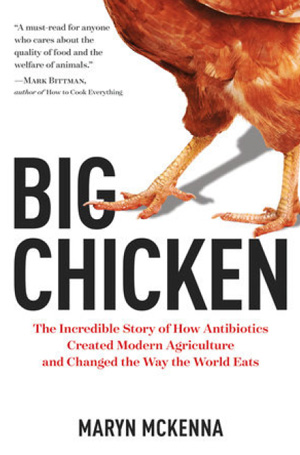

COOPED UP Thanks in large part to antibiotics, chicken production has become heavily industrialized, as detailed in a new book.

Slavko Sereda/Shutterstock

Big Chicken

Big Chicken

Maryn McKenna

National Geographic, $27

Journalist Maryn McKenna opens Big Chicken by teasing our taste buds with a description of the succulent roasted chickens she bought at an open-air market in Paris. The birds tasted nothing like the bland, uniform chicken offered at U.S. grocery stores. This meat had an earthy, lush, animal flavor. From this tantalizing oh-so-European tableau, McKenna hits us with a sickening contrast — scientists chasing outbreaks of drug-resistant Salmonella infections in humans, and ailing chickens living in crowded conditions and never seeing the light of day.

Antibiotics are at the root of both nightmares, McKenna argues. She draws clear connections between several dramatic foodborne outbreaks and the industrialization of chicken production, made possible, in large part, by the heavy use of the drugs. That reliance on antibiotics has also spurred the rise of drug-resistant bacteria. In fact, the overuse of antibiotics in livestock is a bigger driver of resistance than the overuse of antibiotics in people.

Farmers began using the drugs after studies in the 1940s showed that antibiotics boosted muscle mass. For chickens, that meant the birds got bigger and grew faster with less feed. Today, a meat chicken weighs twice what it did 70 years ago at slaughter and reaches that weight in half the time. Once farmers saw opportunity for growth and packed more birds into barns, the drugs took on a new role: to protect crowded animals from illness.

McKenna weaves in real people’s stories with clearly explained scientific details and regulatory history. If this story has a villain, it’s Thomas Jukes, whose noble goal was to feed the world with cheap protein. In the ’50s, Jukes was a researcher at Lederle Laboratories, one of the first manufacturers of antibiotics. He did some of the early studies testing the drugs as growth promoters. He saw signs that bacteria were developing resistance, but he saw no risk to the chickens, McKenna writes. Jukes railed against efforts in the ’70s to regulate antibiotic use in livestock and, up until he died in 1999, refused to acknowledge any downsides.

In addition to profiling farmers who embraced industrialization, McKenna introduces those who have turned their backs on antibiotics. These farmers, including many in the United States, have learned to raise drug-free chickens, mainly by going back to the old ways — letting chickens roam free, day and night, pecking at grubs in the ground. Some farms in the Netherlands even manage to raise industrial numbers of chickens without propping them up with antibiotics.

McKenna’s story almost has a happy ending. In 2014, the fast-food restaurant Chick-fil-A announced it would, within five years, stop serving chicken raised with antibiotics. Chicken producers, as well as McDonald’s, Subway, Costco and Walmart, followed suit.

But we’re not out of the woods yet, McKenna warns. She likens antibiotic resistance to climate change, calling it “an overwhelming threat, created over decades by millions of individual decisions and reinforced by the actions of industries.” The book might not make you give up chicken, but you may be more likely to look for sustainably raised birds to put on the dinner table.

Buy Big Chicken from Amazon.com. Science News is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. Please see our FAQ for more details.