Computer science can help abuse and trafficking survivors regain safety

Nicola Dell is exposing ways technology can be abused in intimate partner violence and human trafficking cases

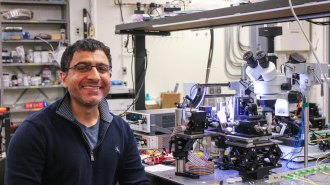

Nicola Dell, a computer and information scientist at Cornell Tech, was awarded a 2024 MacArthur Fellowship for her research on the role of technology in intimate partner violence and human trafficking.

© John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation–used with permission

As technology becomes more ingrained in daily life, domestic abusers and perpetrators of human trafficking are using it in insidious new ways that can target their victims even from a distance. That’s why Nicola Dell, a computer and information scientist at Cornell Tech, studies technology-facilitated abuse and how to stop it. Her pioneering work helps survivors of intimate partner violence and human trafficking so they can regain their personal and digital safety.

Dell’s research focuses on predicting and warding off the potential actions of attackers who can bypass many types of security precautions simply through their intimate knowledge of their targets. For instance, instead of stalking someone by following them in a car or on foot, attackers can now surreptitiously trail their target’s every move using the location tracking technologies on smartphones or other digital devices.

While it’s common for perpetrators to track, stalk, harass or even impersonate the people they intend to harm, this type of technology abuse is understudied by computer scientists. The novel challenges make it “a very interesting [research] space from a human–computer interaction perspective,” Dell says.

In 2018, Dell cofounded the Clinic to End Tech Abuse at Cornell Tech. The first of its kind, CETA offers free consultations to survivors of intimate partner violence. The center helps them uncover ways that their devices and accounts may be compromised, along with steps that they can take to improve and maintain their digital safety and privacy. Due in part to her work at CETA, Dell was awarded a 2024 MacArthur Fellowship, a five-year, $800,000 “no-strings attached” award that recognizes creativity and future research promise.

Rosanna Bellini worked for Dell as a postdoctoral researcher before becoming director of research at CETA. When she met Dell in 2019, Bellini says, “she struck me as someone who’s incredibly smart” and “whose brain works at a million miles an hour.” But Dell’s intelligence wasn’t the only trait that left an impression on Bellini, who is also a computer scientist at New York University.

“I got the sense that her interests in these areas were really authentic,” she says. “There was this element of wanting [to help people] … because it was the right thing to do.”

Stumbling into computer science

Dell was born in Zimbabwe, where she lived until she left for college. “I wasn’t someone who was writing code at age five,” she says. She didn’t start using computers until she was a teenager in the 1990s. When she was around 13 years old, “there was one computer in the library at school,” she says. At her high school, she was one of the first students to take computer science. By then, her school had enough computers for only about 10 students to take that course out of a class of around 150. “I was really lucky to be offered that as an option,” Dell says.

That class helped Dell discover her passion and aptitude for computer science, steering her to major in it at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England. “In many ways, I picked computer science because it sounded cool” and “it seemed like a reasonable thing to do at the time,” she says.

That choice would set her apart in ways that she didn’t expect. Because she went to all-girls’ schools up until then, she wasn’t aware of gender disparities in computing until she had already moved to England. Only then did she realize that she was one about a handful of women at that university pursuing a computer science major. She also discovered that there wasn’t much awareness of the gender gap or support for the women who were grappling with being among the few in the field.

“Being surrounded by a lot of men, particularly many of whom had that childhood of coding since they were small,” was difficult, Dell says. Switching majors wasn’t really an option because the British school system essentially requires that high school students choose their majors when they apply to universities. “I just remember feeling intimidated and then toughing it out.”

When she started a Ph.D. at the University of Washington in Seattle, she was interested in computer graphics and computer vision research. However, once she met her advisor, the late Gaetano Borriello, everything changed. Borriello’s focus was on how technology could help improve the lives of underserved people, and Dell realized that she was drawn toward designing technologies that can work well in low-income or low-resource environments.

Now, Dell’s guidance helps students and junior researchers from diverse backgrounds as they find their places in computer science while working on problems that have both academic and societal impacts.

“For me personally, academia was a world that I wasn’t privy to previously,” says Ian Solano-Kamaiko, a Ph.D. student in computer science at Cornell Tech. He spent several years working as an engineer before starting graduate school, where Dell is one of his two advisors.

“Pursuing a Ph.D. with the goal of remaining in academia — especially at [predominately white] elite institutions like Cornell — is an extraordinarily opaque process characterized by unspoken rules, expectations and procedures,” Solano-Kamaiko says. “It can be disorienting and difficult to navigate. In this context, Nicki has been instrumental. She has helped demystify these opaque structures, advised me on strategic approaches aligned with my career goals and has consistently advocated for me throughout my Ph.D.”

Solano-Kamaiko’s research focuses on computing in health care settings, with an emphasis on studying how personal, social and environmental factors such as where a person was born and live contribute to inequities that affect community and home health care workers. If he ever gets stuck on a problem, Dell encourages him “just to put pen to paper, just to keep putting one foot in front of the other,” he says. “There is this faith that it will all come together.”

Behind the scenes of tech-based violence research

Dell started researching how technology can be abused in intimate partner violence in 2016. She later expanded the scope of her work to include the study of technology abuse in human trafficking. In technology design, it’s typical to consider potential users for a piece of technology and how the design can best serve them, Dell says. “But we often don’t think about adversarial design — or abuseability, as we like to call it.” A totally different approach is needed “to protect you from someone who lives in the same house or who knows your children, knows their birthdates, has access to your email accounts and can open your computer while you’re in the shower,” she says.

For instance, she and her colleagues developed a new algorithm to identify apps that could be used for harassment, impersonation, fraud, information theft and concealment. “As a result of our work, the Google Play Store has already removed hundreds of apps for policy violations,” the researchers wrote in a 2020 conference proceeding.

Dell and her colleagues also created a new framework for analyzing passwordless authentication systems. In these “passkey” services, users can unlock a device with their fingerprint, a scan of their face or a PIN rather than providing a password. While these systems can be easier for legitimate users to navigate, they are also weaponized to harm at-risk users. For instance, abusers can log in to their victims’ smartphones using a known PIN and then add their own fingerprint to the device’s settings. Even if their target later changes their password, the abuser can still access the phone without permission.

Dell and her team looked at 19 passkey services in their study and found that, “In the most egregious cases, flawed implementations of major passkey-supporting services allow ongoing illicit adversarial access with no way for a victim to restore security of their account,” they write.

When Dell finds such vulnerabilities, she notifies tech companies about the issues with their products and potential fixes. “Those are differently received by different companies,” she says. “Some of it also depends on the complexity or difficulty of making changes.”

One big challenge is negotiating “the dual use nature” of technologies that have both legitimate uses and potential abuses, Dell says. Sometimes, that dual nature can be easily navigated through a few careful considerations. For instance, she and her collaborators note that parental monitoring applications that track children’s whereabouts could be abused by perpetrators of intimate partner violence to stalk adults without their knowledge. That finding comes with a clear message for tech companies, Dell says: Tracking tech should not be covert.

“If someone’s tracking your location, there should be a warning,” if there isn’t one already, Dell says. Making that change doesn’t impede the legitimate use of those applications. “Even if it’s a child, the child should know ‘Mommy can see where you are,’” she says.

Achieving balance between security and ease of use is another technology quandary. In case someone gets locked out of their account, say by entering a wrong password too many times, tech companies often offer alternative account access routes. Users can then unlock the device by answering security questions or entering an old password. While these “essentially backdoor methods” are a boon for legitimate users, Dell says, they’re also easily abused.

Dell has interviewed survivors of human trafficking and professional advocates about how technology was used to coerce and control them and how it could be used to help them recover their digital safety and security. She has also analyzed online forum entries written by alleged intimate partner abusers detailing how they have used technology to surveil survivors. That work focuses on understanding the underpinnings of abuse to guide conversations about how to stop it, Dell notes. For instance, her work involves studying how to identify crucial moments in the cycle of intimate partner violence where interventions might be safely applied to prevent or de-escalate harm to survivors.

At CETA, Dell and her team also encourage technology professionals to give back in ways that might be new to them. By opening that center, “one thing we were trying to do is create models for encouraging more pro bono tech work,” she says. Such volunteer efforts are less commonplace in tech than in other industries, such as the legal sector, she says. She has found that students and professionals yearn for those opportunities. Tech volunteers are trained on topics such as intimate partner violence, trauma-informed care and boundary setting.

The center also attracts a different type of volunteer: social workers who want to expand their technology skill sets to better understand what to look for and how to help people mitigate harms. Through those cross-disciplinary partnerships, everyone has a chance to grow their skills for helping real-world survivors of abuse continue to recover their digital safety and security.

“Anyone,” Dell says, “can be trained to make a difference.”