Physicists discovered neutrinos 70 years ago. The ghostly particles still have secrets to tell

The wily nature of the subatomic particles makes them notoriously hard to measure

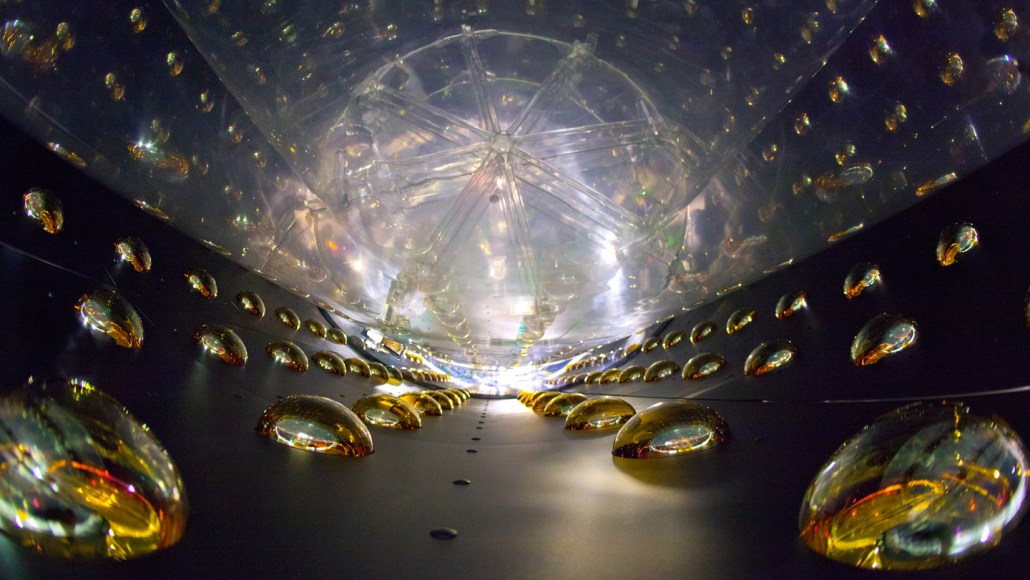

Scientists once doubted that neutrinos could ever be observed. Today, detectors around the world, including at the Daya Bay experiment in China, pick up signals of these ghostly particles.

Brookhaven National Laboratory/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

This is a human-written story voiced by AI.