A new nuclear imaging prototype detects tumors’ faint glow

Doctors could someday use Cerenkov light to detect cancer

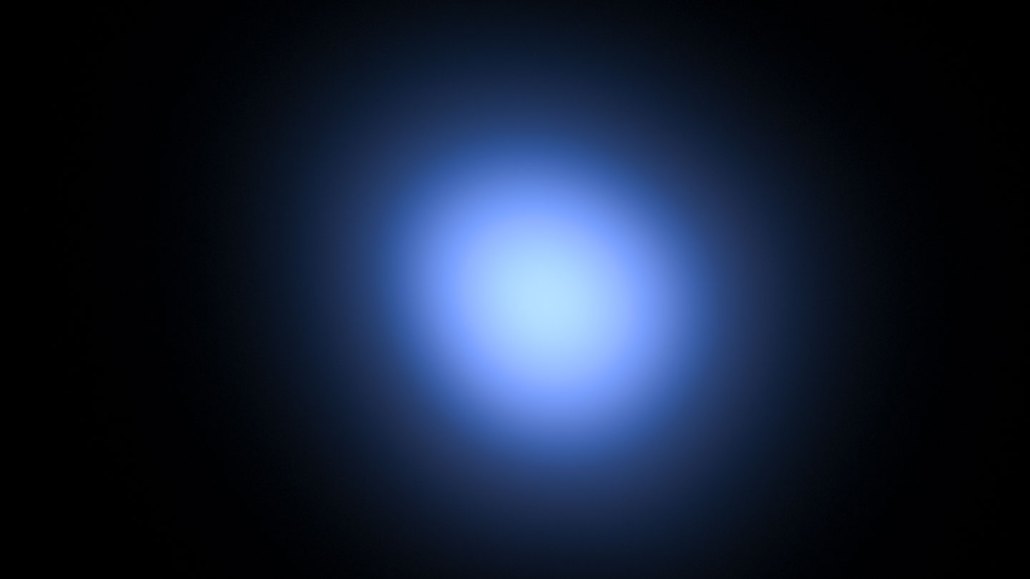

Cerenkov light, generated by high-speed particles traveling faster than light through a material, emits a blue glow. The light can be used to image a variety of cancers, new research shows.

Baac3nes/Moment/Getty Images Plus