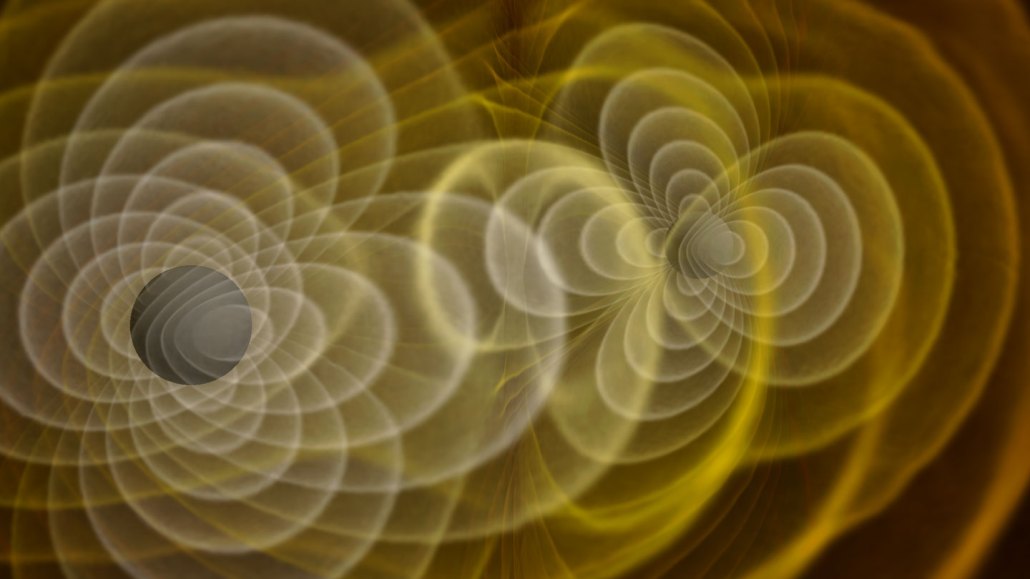

The convergence of two black holes will send gravitational waves rippling through space (illustrated). If moving predominately in a single direction, those waves can shoot the newly unified black hole into space at high speed.

C. Henze/NASA

The convergence of two black holes will send gravitational waves rippling through space (illustrated). If moving predominately in a single direction, those waves can shoot the newly unified black hole into space at high speed.

C. Henze/NASA