There could be little difference in how young salmon survive their journey down a free-flowing river versus the heavily dammed Columbia River system, says a controversial new study.

A new system for tagging small fish allows biologists to monitor young salmon migration survival in a big, undammed river for the first time, David Welch of Kintama Research Corporation in Nanaimo, Canada, and colleagues report online October 28 in PLoS Biology.

The technique also opened the way for a comparison study to check the effects of the dams.

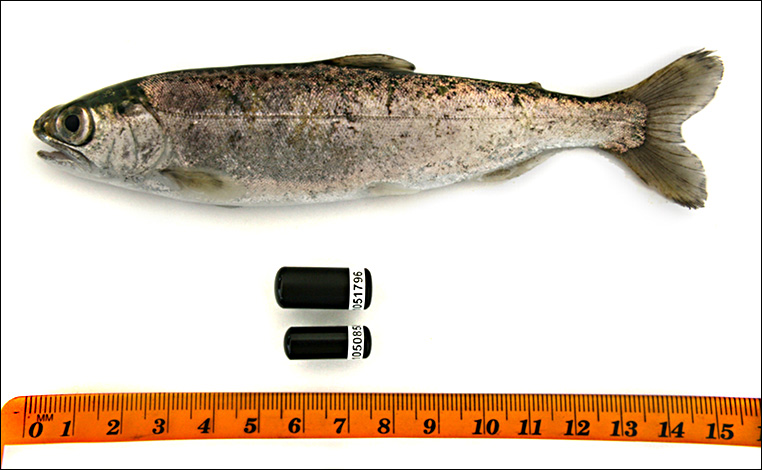

When young salmon reach roughly the size of a hot dog, they leave their upriver hatching grounds and swim hundreds of kilometers to the sea to spend several years there before journeying back upriver to spawn.

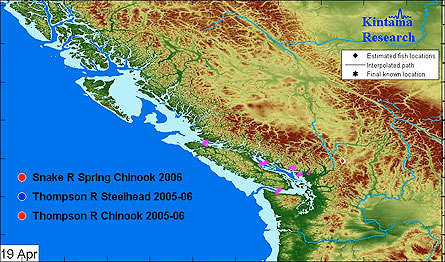

Young salmon swimming seaward down the Snake River and then the Columbia have to navigate past eight hydropower dams. Conservationists have blamed these obstacles for a large share of the shrinking salmon populations in the Pacific Northwest, and engineers have spent billions trying to make the dams less damaging to salmon.

In 2006, Welch and his colleagues used almond-sized tags plus underwater detectors in both rivers and the ocean to monitor young salmon, or smolts. Tagged hatchery Chinook, released in several tributaries of Canada’s Thompson River, swam to the Fraser River and then the Pacific without encountering a big dam.

Chinook smolts didn’t survive any better in the free-flowing Fraser system than a comparison hatchery group did on its journey through the dams in the Columbia system, of which the Snake River is a major tributary, the researchers found.

Just under a third of the Chinook survived the whole trip in both systems. In a sense, the Columbia River system may even have been less destructive despite its dams, Welch says. The smolts there had to cover 910 kilometers, more than twice the distance of the Fraser trip, but still survived in about the same proportion.

“We have discovered something none of us ever thought in our wildest dreams,” Welch says.

Just what that discovery means can be interpreted several ways. “The key message is not that dams are good for salmon,” Welch says.

In the 1960s and ’70s, “absolutely the dams were a problem,” he says. The new findings raise the question of whether as much as is possible has been fixed with dams, and it’s now time to worry about other menaces to the fish.

Or perhaps some unknown menace in the Fraser has degraded it to the level of the dammed Columbia, putting the two rivers on more equal footing for salmon. The analysis in this study focused on the river journey, so perhaps the Columbia’s dams inflict slow-acting damage that impairs or kills fish after they get out to sea.

Fisheries biologist Jack Stanford says that actually he’s not surprised and finds it plausible that survival rates turn out about the same in the two river systems. Even a decade ago salmon travel through the Columbia dam zone “was getting very good with the new bypass systems,” says Stanford, who directs the University of Montana’s Flathead Lake Biological Station.

There has been so much concern about dams that some big problems in the Columbia tend to get ignored, says Thomas Quinn, a trout and salmon ecologist at the University of Washington in Seattle. Those other problems, he says, include habitat destruction in the tributaries, overproduction in hatcheries and “cutting management too close to the bone.” So dams indeed may be paling in comparison to other troubles. He hasn’t pored over the details of the tracking in the new study, but “I do not find the results implausible,” Quinn says.

Once-mighty runs of wild salmon in the Pacific Northwest have dwindled to the point where the United States lists 13 stocks of salmon species, including some Chinook, in the Columbia system as either threatened or endangered.

Monitoring salmon populations has presented technical challenges. Earlier tags, called PITs, proved practical only in dammed rivers with chutes that funneled fish into a small space so a detector could pick up the tags at close range. Monitoring fish swimming through free-flowing water became feasible only with the new tags and detectors.

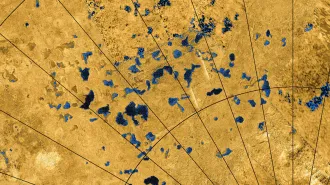

The international Census of Marine Life has deployed the new monitoring system, nicknamed POST, along the Pacific Coast from California to Alaska. Lines of detectors pick up the ping of individual ID tags going by, and research ships can download the data without having to haul up the detectors.

This new system allowed Welch and his colleagues to track the Chinook, as well as young steelhead trout, with the surgically implanted detectors. The system has even picked up two of the youngsters along the continental shelf off Alaska and could answer questions about the next big problem salmon conservationists face: What’s happening to the smolts when they get out to sea?