Global inequity in COVID-19 vaccination is more than a moral problem

Lopsided distribution will cost lives, ding the global economy and perpetuate the pandemic

COVAX, the international initiative to vaccinate the globe more equitably, made its first shipment of vaccines on February 24 to Ghana. Here, a worker checks the shipment, which includes 600,000 doses of AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccines.

Francis Kokoroko/REUTERS

- More than 2 years ago

Read another version of this article at Science News Explores

Months before the first COVID-19 vaccine was even approved, wealthy nations scrambled to secure hundreds of millions of advance doses for their citizens. By the end of 2020, Canada bought up 338 million doses, enough to inoculate their population four times over. The United Kingdom snagged enough to cover a population three times its size. The United States reserved over 1.2 billion doses, and has already vaccinated about 14 percent of its residents.

It’s a drastically different story for less wealthy nations. As of March 4, more than 80 had yet to administer a single dose. Only 55 doses in total have been delivered among the 29 lowest-income countries, all to Guinea. Only a few sub-Saharan African countries have begun systematic immunization programs.

“The world is on the brink of a catastrophic moral failure, and the price of this failure will be paid with lives and livelihoods in the world’s poorest countries,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization, recently said.

COVAX, an international initiative tasked with ensuring more equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines, aims to redress this imbalance by securing deals that send shots to low-income countries free of charge. Despite new pledges of support from some of the wealthiest nations, COVAX is off to a slow start. Its first shipment of 600,000 shots was sent February 24, to Ghana. COVAX still needs at least $2 billion, potentially more, to meet its goal of vaccinating 20 percent of participating countries by the end of the year.

Such stark inequities don’t just raise moral questions of fairness. With vaccine demand still vastly outstripping supply, lopsided distribution could also ultimately prolong the pandemic, fuel the evolution of new, potentially vaccine-evading variants, and drag down the economies of rich and poor — and vaccinated and unvaccinated — nations alike.

“I think the leaders of rich nations have done a very poor job explaining to their citizens why it’s so important that vaccines are distributed worldwide and not just within their own nation,” says Gavin Yamey, a global public health policy expert at Duke University. “No one is safe until all of us are safe, since an outbreak anywhere can become an outbreak everywhere.”

Vaccine inequity could breed vaccine-evading variants

Here’s why a new coronavirus outbreak anywhere can become an outbreak everywhere: Viruses mutate.

It’s normal and happens by chance as a virus replicates inside a host. Most mutations are harmless, or hurt the virus itself. But every so often, a tiny genetic tweak makes the virus better at infecting hosts or dodging their immune response. The more a virus spreads, the more opportunity that one (or more likely a handful) of these tweaks could birth a new, more threatening strain.

This is already happening. In December, scientists detected a new variant, dubbed B.1.1.7 in the United Kingdom. It soon became clear that it had acquired mutations that made it more infectious (SN: 1/27/21). In just a few months, that variant has circled the globe, popping up in more than 70 countries, including the United States.

Another variant first detected in South Africa is also more transmissible — and appears to be slightly less affected by existing vaccines (SN: 1/27/21). It too has spread worldwide. Variants detected in California and New York are now raising concern too. As long as widespread viral transmission continues, new variants will emerge.

“It’s uncertain at this point whether we’re going to have to continually chase this virus and develop more vaccines,” says William Moss, the executive director of the International Vaccine Access Center at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The more the virus replicates, the more opportunity it has to evolve around existing vaccines or natural immune responses to older variants, Moss says. Large pockets of unvaccinated people can serve as incubators for new variants. The longer such pockets persist, the greater the chance of variants accumulating changes that make them more and more resistant to vaccines. Eventually, such variants might invade well-vaccinated countries that thought themselves safe.

Barely vaccinated populations might be especially fertile grounds for vaccine-evading variants, says Abraar Karan, an internal medicine physician at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. In a vaccinated individual, mutations that even slightly evade that induced immune response can get a foothold. Unless that variant completely evades vaccines, which is unlikely, its spread will be blunted by a well-vaccinated population. But if most of a region remains totally naïve to infection, that new variant could burn quickly through the largely unvaccinated population, fueling the changed virus’ spread to other regions.

In Israel, where cases have fallen after more than 40 percent of the population has received at least one vaccine dose, the health ministry has reported at least three cases of reinfection by the South African variant in non-vaccinated people. That’s a very small sample, but indicative of the threat posed by uneven vaccination rates globally.

“If we want to stop the spread we have to stop it everywhere, starting with the most vulnerable,” Karan says. “Otherwise we’re going to see continued outbreaks and suffering.”

“No economy is an island”

Protecting people from getting sick is obviously a big driver of the rush to vaccinate in wealthy nations, many of which have been hit hard by the virus. Vaccines are also seen as a way out of the largest global economic downturn since World War II, roughly a 4.4 percent dip. But an inequitable distribution of vaccines could imperil a robust and quick recovery, experts say.

If extended outbreaks, lockdowns, sickness and deaths continue in countries with less access to vaccines, all economies will suffer, says Selva Demiralp, an economist at Koç University in Istanbul. “No economy is an island,” she says, “and no economy will be fully recovered unless others are recovered, too.”

Extreme vaccine inequity could cost the global economy more than $9 trillion dollars in 2021, about half of which would come from rich nations, Demiralp and her colleagues reported January 25 in a paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research. In that scenario, wealthy nations largely vaccinate their populations by midyear, but leave poorer nations out completely.

Everybody takes a hit thanks to the interconnectedness of the global economy. The production process to build a Volkswagen or iPhone, for instance, spans continents. Disruptions to one link of that supply chain, say steel manufacturing in Turkey, ripple throughout. Today’s marketplace is global, too: Diminished demand for goods in countries saddled with coronavirus restrictions will affect the bottom line of companies headquartered in wealthy nations. “As infections rise in a country, both supply and demand can decrease,” Demiralp says.

She and her colleagues estimated these virus-induced fluctuations in supply and demand by combining a statistical model of how coronavirus spreads with vast amounts of economic data across 35 sectors in 65 countries. By tweaking the pace and extent of vaccination, the team estimated total costs to each country under different scenarios. The $9 trillion number represents extreme inequity. But less extreme gaps are still very expensive.

If rich countries vaccinate their entire populations in four months, while the lowest-income countries vaccinate half their population by the end of 2021, global gross domestic product this year will fall by between $1.8 trillion and $3.8 trillion, with rich countries losing about half of that, the team calculated.

Those costs could be averted with a much smaller investment, on the order of tens to hundreds of billions of dollars, in distributing vaccines globally. “It’s a no brainer,” Demiralp says. “It’s not an act of charity. It’s economic rationality.”

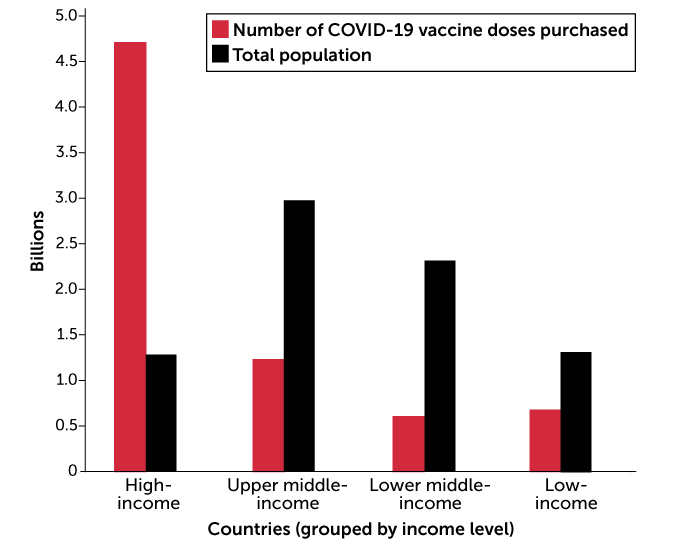

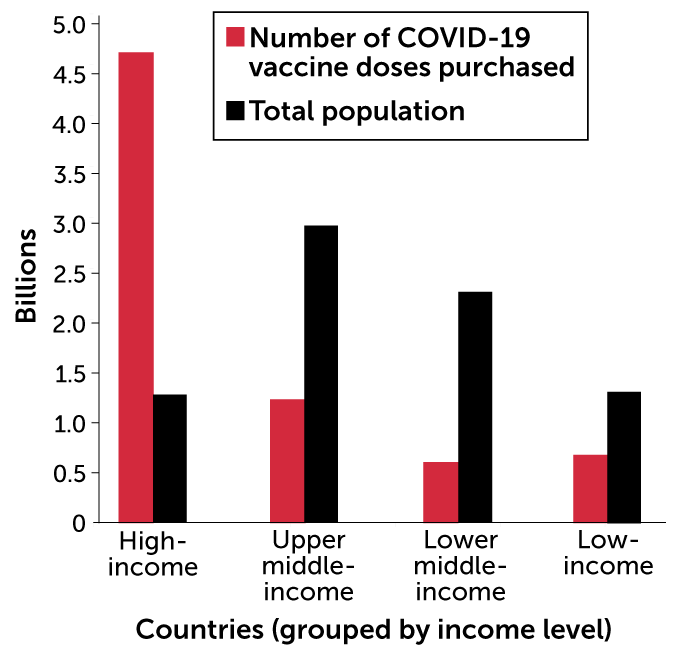

Unequal distribution

To date, high-income countries have purchased many more vaccine doses than less wealthy countries. Duke Global Health Innovation Center collated purchase data from countries in each World Bank income grouping, though not all countries in each income grouping were included in the analysis. The purchased doses are compared with the total population of countries included in each income grouping.

COVID-19 vaccine doses purchased by countries, grouped by income

Evening the playing field

COVAX is trying to even the vaccine playing field — but with limited success so far. There are a lot of hurdles, from securing scarce doses to ensuring that countries have the infrastructure to handle them. That could mean equipping some countries with more ultracold refrigerators to store vaccines (SN: 11/20/20) to revamping mass vaccination programs designed for kids to work for adults too. “Equitable distribution will take a lot more than just securing vaccines,” says Angela Shen, a public health expert at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Vaccine Education Center.

Three global public health powerhouses lead the international initiative: the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization, the World Health Organization and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. COVAX uses funds from governments and charitable organizations to buy up doses from pharmaceutical companies and distribute them to lower-income countries free of charge.

For starters, COVAX plans to distribute 330 million doses to lower-income countries in the first half of the year, enough to vaccinate, on average, 3.3 percent of each population. Meanwhile, by June many rich nations will be well on their way to vaccinating most of their populations.

All told, COVAX says it’s reserved 2.27 billion doses so far, enough to vaccinate 20 percent of the populations of 92 low-income countries by year’s end. Actually meeting that goal is contingent on raising at least $8 billion. On February 19, several countries pledged further support to COVAX, including $2 billion from the United States. Still, COVAX is billions short.

“Money is not the only challenge we face,” WHO’s Ghebreyesus said in a Feb. 22 news briefing. Deals between wealthy nations and pharmaceutical companies threaten to gobble up global vaccine supply, reducing COVAX’s access. “If there are no vaccines to buy, money is irrelevant.”

Sign up for our newsletter

We summarize the week's scientific breakthroughs every Thursday.

People getting vaccinated, in any country, is something to be celebrated, says Yamey, of Duke University, “but it should disturb us to know that low-risk people are going to get vaccinated in rich countries well ahead of high-risk people in poor countries.” A more equitable rollout, Yamey says, would prioritize healthcare workers and vulnerable people in all countries. “I don’t see that happening in any scenario unfortunately.”

Even if COVAX achieves its goal this year, these countries will be far from reaching herd immunity, the threshold at which enough people are immune to a pathogen to slow its spread (SN: 3/24/20). Estimates to reach that herd immunity range from 60 to 90 percent of a population.

“Many low-income nations won’t have widespread vaccination until 2023 or 2024, because they can’t get the doses,” Yamey says. “This inequity is due to hoarding of doses by rich nations, and that me-first, me-only approach ultimately goes against their long-term interests.”