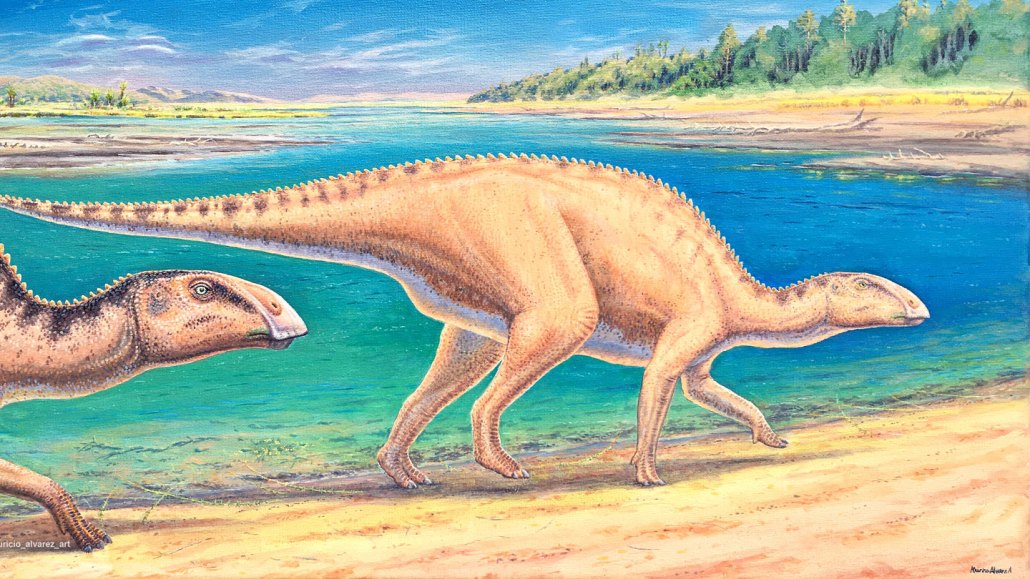

Gonkoken nanoi, illustrated here, lived 72 million years ago in what is now subantarctic Chile. The creature belonged to a lineage of duck-billed dinosaurs that had since gone extinct elsewhere in the world.

Mauricio Álvarez Abel

Fossils from the southern tip of Chile are adding a wrinkle to researchers’ understanding of how duck-billed dinosaurs conquered the Cretaceous world.

Duck-billed dinos known as hadrosaurids were highly successful and lived on most continents by the end of the Cretaceous, about 66 million years ago. Now, a study shows that an older duck-billed lineage appears to have thrived some 72 million years ago in subantarctic South America, potentially millions of years before hadrosaurids reached the continent, researchers report June 16 in Science Advances.

“It’s yet another chapter in the dispersion of these dinosaurs that we did not know about,” says Jhonatan Alarcón-Muñoz, a paleontologist at the University of Chile in Santiago.

About a decade ago, paleobiologist Marcelo Leppe of the Chilean Antarctic Institute in Punta Arenas was searching for plant fossils in the Río de las Chinas Valley in Chile’s Magallanes region when he spotted fossilized bones. After bringing the finding to the attention of Alexander Vargas, a paleontologist at the University of Chile, researchers extracted the bones for study.

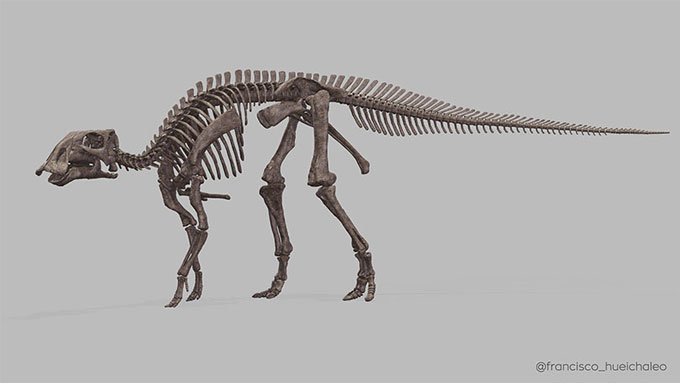

Alarcón-Muñoz, Vargas, Leppe and their colleagues determined the bones belong to a new type of duck-billed dinosaur — herbivorous giants that had flattened, waterfowl-like snouts. The remains included many body parts, with pieces of hip, limbs, ribs, vertebrae and skull recovered.

The researchers named the animal Gonkoken nanoi, “gon” and “koken” being the words for “similar to” and “wild duck or swan” in the language of the Indigenous Aónikenk people from the part of southern Patagonia where the bones were found.

In all, the researchers suspect they found four distinct Gonkoken individuals. No remains of other animals were found with them, suggesting the dinosaurs were probably moving in a herd, Vargas says (SN: 7/9/14).

Gonkoken isn’t like other known South American duck-billed dinosaurs, or like any from the old southern supercontinent of Gondwana, which included what came to be South America. Until now, all known duck-billed dinosaurs from Gondwana were hadrosaurids, which had their heyday in the late Cretaceous and had such efficient, stacked, plant-pulverizing teeth that they chewed their way to nearly global dominance, outcompeting other herbivorous dinosaur groups. Gonkoken appears to be part of an older, less specialized lineage that diverged from other duck-billed dinosaurs around 91 million years ago, before the first hadrosaurids evolved, the researchers say.

Gonkoken’s ducklike snout had a simpler construction than that of hadrosaurids, Alarcón-Muñoz says, and it had fewer rows of teeth in its chewing surface. Gonkoken was also relatively small — about four meters long — while some hadrosaurids were true titans, reaching about 15 meters in length.

Seeing a non-hadrosaurid duck-billed dinosaur in South America like Gonkoken is “somewhat unexpected,” says David Evans, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Toronto who wasn’t involved in the research. The discovery “makes us rethink their biogeographic history in the Americas in interesting ways.”

For example, rather than a single colonization of the continent, the team thinks that duck-billed dinos arrived in South America from North America in two separate waves. “We suspect our kind of duck-billed dinosaur arrived earlier into South America and reached further south than the hadrosaurids,” says Alarcón-Muñoz, describing Gonkoken as a relict. “In most other places of the world, this kind of dinosaur had already gone extinct by this time.”

The findings may also mean that hadrosaurids were not quite as widespread as previously thought. Fragmentary remains in southern Patagonia and Antarctica that were thought to belong to hadrosaurids may actually be Gonkoken or its close relatives.

Many other outcrops along the Río de las Chinas are studded with dinosaur bones. The researchers want to examine these to see if they belong to Gonkoken as well. Finding more skull bones of Gonkoken, Evans says, could be key for figuring out exactly how it was related to other duck-billed dinosaurs.