Humans have shockingly few ways to treat fungal infections

Antifungal vaccines and drugs are in the works, but progress is achingly slow

Fungi-infested zombies in The Last of Us are hard to kill. Fungal infections are on the rise in the real world, and while they don’t zombify people, there are precious few antifungal treatments.

Courtesy of HBO

Fighting fungi isn’t easy.

Season two of the streaming series The Last of Us has arrived on Max (light spoilers ahead), bringing viewers back to a world where people combat zombies puppeteered by a mind-controlling fungus. Guns and flames help the characters survive onscreen. In the real world, fighting fungal infections is less action-packed, but no less fraught.

At the heart of the show is Ellie (Bella Ramsey), a girl immune to the pandemic fungus. The new season picks up after Joel (Pedro Pascal) saves Ellie from a doctor who wanted to remove her brain to find the source of her immunity and make a cure.

That questionable approach aside, the science behind The Last of Us is chillingly real in some respects. While it’s unlikely that fungi now capable of controlling insects or spiders could evolve to zombify humans, climate change is contributing to the spread of fungal infections such as Candida auris and valley fever.

Still, some scientific questions from the show — and the video games on which the series is based — linger. To explore how one might gain immunity against fungi and what tools are becoming available to fight real fungal infections, Science News spoke with experts who are developing potential antifungal vaccines and drugs.

Can a person become immune to fungi?

Yes, to some fungi at least, and that immunity can last a lifetime for many people, says Edward Robb, a veterinarian and chief of strategy for Anivive, a pet pharmaceutical company based in Long Beach, Calif. For example, people who grow up in parts of the American Southwest may develop lifelong immunity to Coccidioides fungi that cause valley fever, he says.

And yet some fungi can infect us over and over again. Yeast infections, ringworm, athlete’s foot and other fungal skin infections often reoccur, so it’s not clear if people can become immune to those.

“Precisely what it would take to become immune to a fanciful fungus like in The Last of Us, I haven’t got a clue,” says John Rex, chief medical officer of F2G Ltd., an international company headquartered in Cheshire, England, that is developing antifungal drugs. But immunity to real fungal infections is easier to explain.

While nearly everyone breathes in at least a few spores regularly, the immune system can keep those from establishing a full-blown infection. But as the microbes expand their ranges and humans build in deserts, scrubland and other places where fungi thrive, more people are encountering more fungi, Robb says.

“The [individuals] that are most susceptible would be people who have high exposure to spores, which could be somebody working in landscaping or construction, somebody going camping,” or doing other things that expose them to dust containing spores, he says.

People taking immune-suppressing drugs and older people whose immune systems are no longer robust may also be susceptible to infection. Individuals new to areas where fungal diseases are common — such as valley fever (also called coccidioidomycosis) — may also be at higher risk of infection because their immune systems haven’t been trained to fight it.

Where would the source of fungal immunity be located?

Definitely not in the brain, Rex says. In Ellie’s case, “she’s immune. The fungus didn’t get any further than her skin.” In fact, once real-world fungi like the ones that cause valley fever reach a person’s brain, “it’s incurable. You can slow it down with existing drugs, but you can’t cure it.”

The immune system consists of various types of white blood cells, some of which produce antibodies and others that help kill invaders in different ways. Antibodies are generally too small to take down relatively large fungal cells, Robb says. Instead, immune cells known as T cells are the fungi fighters. These can be found in the blood, bone marrow and lymph nodes.

How some fungi can make you sick

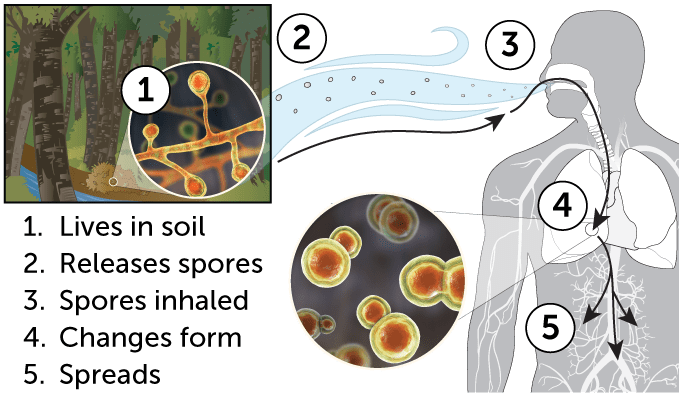

Many fungi that can cause lung infections, including Histoplasma, Blastomyces and Coccidioides species, live in the soil as molds. Those molds make spores, which people often breathe in. In the lungs, the fungi change to a yeast form that causes flulike symptoms, pneumonia or chronic disease. The yeast can spread to other parts of the body and cause serious disease. One potential vaccine uses a genetically altered form of Coccidioides that can’t switch to the yeast form. That vaccine candidate is being tested for use in dogs and people.

Is it possible to make a vaccine against fungi?

Probably, though no one has yet made one approved for use in people.

Robb’s company, Anivive, is developing vaccines against two fungal diseases, valley fever and blastomycosis, that affect both dogs and humans. The same version of the valley fever vaccine being tested in dogs is also in early stages of study for use in people, Robb said during a presentation at the World Vaccine Congress Washington, which was held in late April in Washington, D.C. Currently, antifungal drugs can treat infections, he said, but “the only preventative is not to breathe, and so far that hasn’t worked out so well.”

About 10,000 to 20,000 people in the United States, mostly in Arizona and California, get valley fever each year, and 200 die on average, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases can vary depending on climate and weather conditions, but in some places, it appears to be on the rise. In Arizona, just under 11,000 people contracted valley fever in 2023. That number jumped to 14,770 in 2024 and as of May 6, more than 5,500 people have already been diagnosed with the disease. California saw a similar jump in cases. In 2023, about 9,200 people got valley fever. That rose to 12,637 in 2024. As of March 31, more than 3,100 people have been diagnosed with valley fever in the state.

“There are fungal infections you can get for which we have no current licensed therapy whatsoever.”

John Rex

chief medical officer of F2G Ltd.

Anivive’s vaccine is a live fungus genetically altered to prevent it from changing shape to infect people and animals. The vaccine fungus can’t start an infection but can train the immune system to attack fungi it encounters in the future, animal experiments suggest.

Other groups are also working on vaccines against valley fever and other fungal infections, but it could be years before any make it to market.

Are there other ways to treat fungal infections?

Yes, with antifungal drugs. But there are few options, and some fungi are developing resistance to some of the drugs, the World Health Organization warned April 1 in its first-ever report on treatments for fungal infections.

Only four new antifungal drugs have been approved in the last decade in the United States, Europe or China. Another nine are in development, but just three of those have reached the final stages of testing in people. That means few new antifungal drugs are likely to be approved in the coming decade.

When treating bacterial infections, doctors usually have a variety of antibiotics to choose from. But “our collection of [antifungal] drugs has never been as thorough as it has been for bacteria,” Rex says. “There are fungal infections you can get for which we have no current licensed therapy whatsoever.”

Rex’s company, F2G, is in the final stages of clinical trials for an antifungal drug called olorofim. This drug prevents fungi from making pyrimidines, a type of building block for DNA and RNA. Interfering in that process prevents fungi from replicating and can kill some dangerous fungi, including Aspergillus species. If the drug is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, it will have been about a 25-year journey.

That long road is just one reason there are so few antifungal options, Rex says. “If you want a new antifungal, you should have started 25 years ago.”