Climate change could raise the risk of deadly fungal infections in humans

Outbreaks of Candida auris have recently erupted around the world

FUNGAL THREAT An emerging fungus called Candida auris (illustrated) can cause deadly infections in people’s blood and organs.

Dr_Microbe/iStock/Getty Images Plus

While fungal diseases have devastated many animal and plant species, humans and other mammals have mostly been spared. That’s probably because mammals have body temperatures too warm for most fungi to replicate as well as powerful immune systems. But climate change may be challenging those defenses, bringing new fungal threats to human health, a microbiologist warns.

From 2012 to 2015, pathogenic versions of the fungus Candida auris arose independently in Africa, Asia and South America. The versions are from the same species, yet they are genetically distinct, so the spread across continents couldn’t have been caused by infected travelers, says Arturo Casadevall of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Instead, each continents’ C. auris may have become tolerant of the average normal body temperature of humans — about 37° Celsius — because the fungi acclimated to warming in the environment caused by climate change, Casadevall and colleagues argue. If this hypothesis turns out to be true, C. auris “may be the first example of a new fungal disease emerging from climate change” that poses a risk to humans, the researchers report online July 23 in mBio.

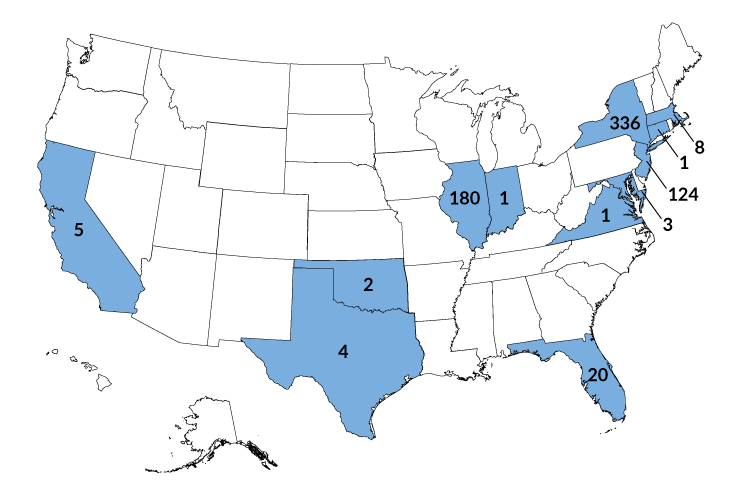

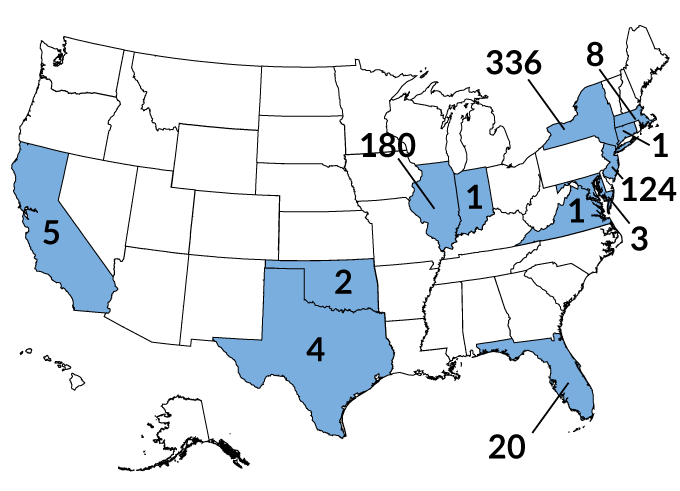

National outbreaks

New York, New Jersey and Illinois currently have the highest number of confirmed cases of C. auris in the country.

Confirmed cases of Candida auris in the United States as of May 31

Since mid-2016, when reporting of C. auris infections began in the United States, there have been nearly 700 cases confirmed in 12 states, with deadly outbreaks occurring among patients in hospitals and other health care facilities. More than 30 countries around the world have also reported cases. The fungus causes dangerous infections of the blood, brain, heart and other parts of the body. Studies show that an invasive infection can be fatal 30 to 60 percent of the time. And some infections are resistant to all available antifungal medications.

Hospitalized patients tend to have weakened immune systems. But C. auris wouldn’t have been a health concern without first developing the ability to replicate inside people, Casadevall says, and it had to become more tolerant of warmer temperatures to do that.

Past work has shown a fungus can be coaxed to grow at warmer temperatures in a laboratory setting. “There are millions of fungal species out there,” Casadevall says. “As they adapt to a warmer climate, some of them will then have the capacity to breach our thermal defenses.”

Meanwhile, other fungi are wreaking destruction on many animals and plants, including frogs (SN: 4/27/19, p. 5), snakes (SN: 1/20/18, p. 16) and trees (SN: 5/3/03, p. 282). “A lot of our fellow creatures are being wiped out,” Casadevall says. And while mammals have tended to be “remarkably resistant to invasive fungal diseases,” he says, bats have been hit hard by outbreaks of a fungus that causes white nose syndrome in part because their body temperature drops during hibernation (SN Online: 7/15/19).

“The fungal kingdom is just so vast,” Casadevall says. If another fungus dangerous to humans can evolve to “defeat our thermal barrier, who knows what it will do to us?”