How alien ‘canals’ sparked debate over life on Mars

A new book details the turn-of-the-century Mars craze

Beginning in 1877, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli observed narrow lines on Mars that he called canali, Italian for “channels.” His observations helped set off a turn-of-the-century Mars craze.

Science History Images/Alamy

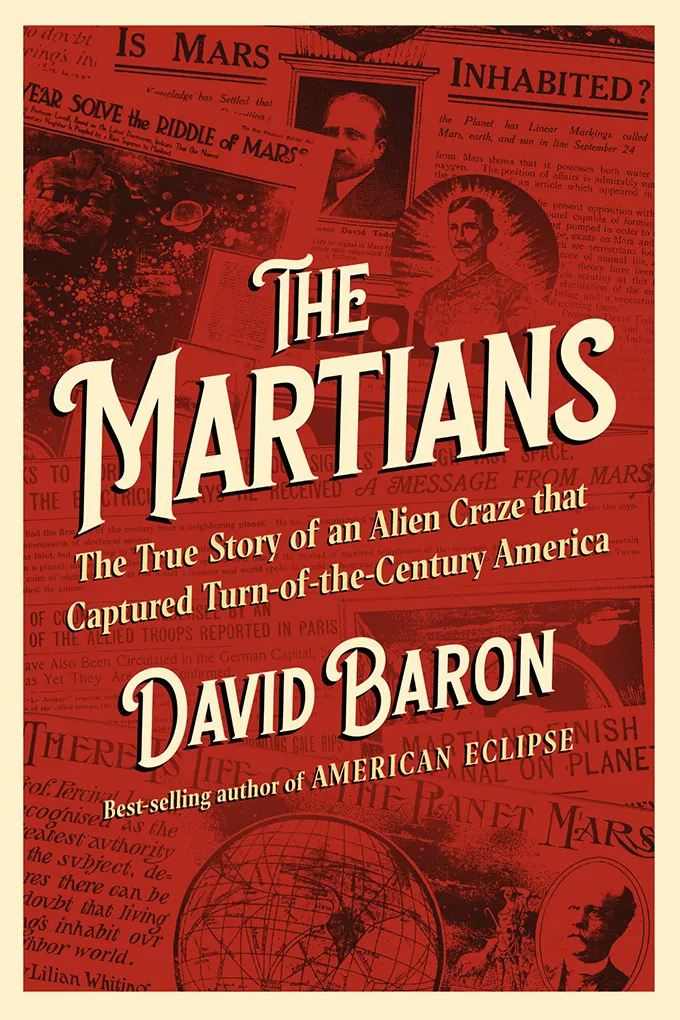

The Martians

David Baron

Liveright, $29.99

It’s not aliens. It’s never aliens.

Claims of extraterrestrial life are so common that experts now have this cheeky retort at the ready. In The Martians, journalist David Baron considers an early, influential example of the “it’s not aliens” phenomenon: the turn-of-the-century Mars craze, during which many people became convinced that earthlings had neighbors on Mars. By digging through historical archives, Baron dredges up new details on some of the major players and events of the time.

From the late 1800s through the early 1900s, a Mars mania gripped the world, and the United States in particular. Newspapers blared with sensationalist headlines. (One example: “Scientists now know positively that there are thirsty people on Mars.”) Astronomy lectures tantalized the public. Theater performances envisioned hypothetical interactions with Martians. Advertisers hitched themselves to the trend to sell their products. Even Alexander Graham Bell was convinced.

The frenzy was sparked by apparent linear features on Mars, observed by multiple astronomers through various telescopes. The lines were dubbed “canals,” which were claimed by one faction of astronomers, despite shaky evidence, to have been constructed by intelligent life for irrigation. The canals, we now know, were illusions. More detailed observations taken in 1909 suggested that they were either irregular natural features or didn’t exist at all. But until then, the canals seemed very real to some particularly vocal observers.

Among the most notable proponents was American astronomer Percival Lowell, an aristocrat who used his wealth to fund his observations of the planet. Alongside Lowell, the book follows several other scientists, including inventor Nikola Tesla, who claimed to have detected Martian messages to Earth. Other Mars enthusiasts make cameos, including science fiction writer H.G. Wells, who published his famous extraterrestrial-invasion story, The War of the Worlds, during this period, and journalist Garrett Serviss, who was agnostic about the canals’ existence but supplied eager readers with the latest information.

Greedily encouraged by the yellow journalism of the era, canal believers engaged in wild speculation, debating the possibilities for Martians’ appearance, their culture and the purported vegetation of the planet they supposedly inhabited. That clamor mostly drowned out the sober voices of many other scientists, who argued there was no evidence for canals, much less for life that created them.

The idea of life on Mars lodged itself in the public consciousness in ways that persist today. Baron recounts a comment by zoologist Edward S. Morse, who suggested that Martians might be similar to creatures on Earth that thrive under diverse conditions, including ants. Henceforth, Martians became antennaed.

Baron doesn’t shy away from calling out the racism in the public’s view of Martians, which sometimes seemed an extension of the exotification of people of color: During a trip to Algeria, Lowell compared the locals to Martians. And Martians were sometimes depicted with exaggerated features reminiscent of racist imagery of Black people.

The saga of Mars’ canals poses a cautionary tale for scientists who followed Lowell. He aimed to follow scientific principles but was misled by his own bias. Still, his work pushed science forward. He financed an expedition to take hundreds of photos of the Red Planet. The Mars craze also inspired innumerable children who would grow up to be scientists or science popularizers, including rocketry pioneer Robert Goddard, astronomer Carl Sagan and science fiction editor Hugo Gernsback.

Baron mostly confines his commentary to the era of the Mars craze, but in reading, one can’t help but consider current events. In recent years, prominent astronomers have claimed to have seen potential signs of life on an exoplanet and evidence of an alien spacecraft in the solar system in announcements that quickly drew criticism from other scientists. More broadly, the warping of science to argue for unsubstantiated but sensational conclusions — that vaccines cause autism or that climate change is a hoax, for example — is a persistent problem.

Part of the reason the Martian craze took off, Baron argues, was because people wanted to believe. The creatures, apparently capable of irrigating their entire planet and sharing water with one another, were depicted as wise and good, living in harmony — a vision of a civilization earthlings could only dream of.

Buy The Martians from Bookshop.org. Science News is a Bookshop.org affiliate and will earn a commission on purchases made from links in this article.