Future Martians will need to breathe. It won’t be easy

Creating an Earthlike atmosphere is just one of many challenges to making Mars habitable

Science fiction easily settles humans on Mars. To make that a reality, we’d need to make the planet more Earthlike. But creating the air we need to breathe is a tall task.

Ollie Hirst

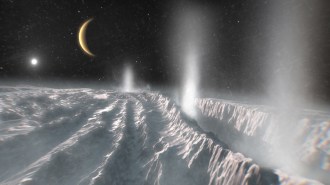

A spacecraft slowly descends to the surface of Mars. Once arid and lifeless, the Red Planet is now lush and green. As a city comes into view, passengers see people strolling along busy streets, venturing into a park and breathing the Martian air.

Many science fiction writers have envisioned futures like this for Mars. In these stories, humans use terraforming technology to make other planets more Earthlike. It’s a huge challenge. To start, Mars would need an atmosphere with enough oxygen and that’s thick enough to retain heat, allowing water to exist as a liquid.

In Earth’s atmosphere, such greenhouse gases as carbon dioxide, methane and water vapor trap the sun’s heat. Carbon dioxide makes up most of Mars’ atmosphere, but there’s not enough to trap heat. Less dense than Earth and half its size, Mars has weaker gravity, so it’s “harder for it to hang on to an atmosphere,” says Paul Byrne, a planetary scientist at Washington University in St. Louis.

So future Martians would first need a way to produce enough CO₂ to fill an entire atmosphere and jump-start the greenhouse effect, Byrne says. One idea is extracting CO₂ from Mars itself, creating the gas from carbon and oxygen in Martian minerals or releasing CO₂ trapped in Mars’ polar ice caps or below the surface. But, he says, “there probably isn’t enough to make an atmosphere even close to what we would need.”

Using spacecraft observations, researchers have estimated that the entire planet would produce enough CO₂ to thicken the atmosphere to only about 7 percent of Earth’s, not enough to create a significant greenhouse effect.

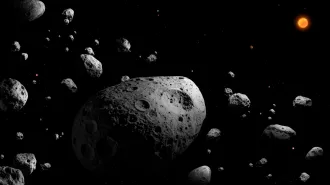

Other scientists suggest triggering volcanic eruptions to pump out CO₂. Future civilizations might try to redirect asteroids to create these eruptions. Humankind has already inched toward that feat, says MIT astrophysicist Sara Seager. In 2022, NASA’s DART spacecraft bumped the asteroid Dimorphos closer to the larger rock it orbits.

But you’d probably need to whip a lot of space rocks at Mars to release enough CO₂ for an atmosphere, says Byrne. And the speed of incoming asteroids would cause “catastrophically damaging impacts.”

Let’s say future engineers do figure out some way to warm and thicken up Mars’ atmosphere. Then Mars colonists would want to start tweaking it to resemble Earth’s. “We [would] need to have enough free oxygen that we can breathe,” Byrne says. Free oxygen, a form not chemically bonded to other elements, makes up about 21 percent of the air we breathe. The rest is mostly nitrogen, with a smattering of other gases.

Oxygen-producing microbes could help replicate this blend. Research suggests cyanobacteria kicked off a rise in free oxygen on Earth a little over 2 billion years ago. Tweaking genes of these microbes could help them withstand Mars’ extreme environment.

Through photosynthesis, these tiny workers can take in CO₂ and pump out breathable oxygen. That’s probably safer than relying on machines to make oxygen. With machines, Seager says, “if one little thing goes wrong, we’re all dead.”

Engineers would also face other hurdles to terraforming Mars, from toxic salts called perchlorates on the dusty surface to deadly radiation from the sun and space, since Mars has no magnetic field to shield it.

Space agencies are working to get the first astronauts to Mars, maybe within the next decade. But it could take anywhere from a few hundred to several thousands of years to perfect terraforming tech, Byrne says. “Certainly nothing remotely in our time.”

The stakes are high. Small malfunctions to terraforming tech could be catastrophic. “We’re just so fragile,” Seager says. “That’s why the whole terraforming question is so challenging.”