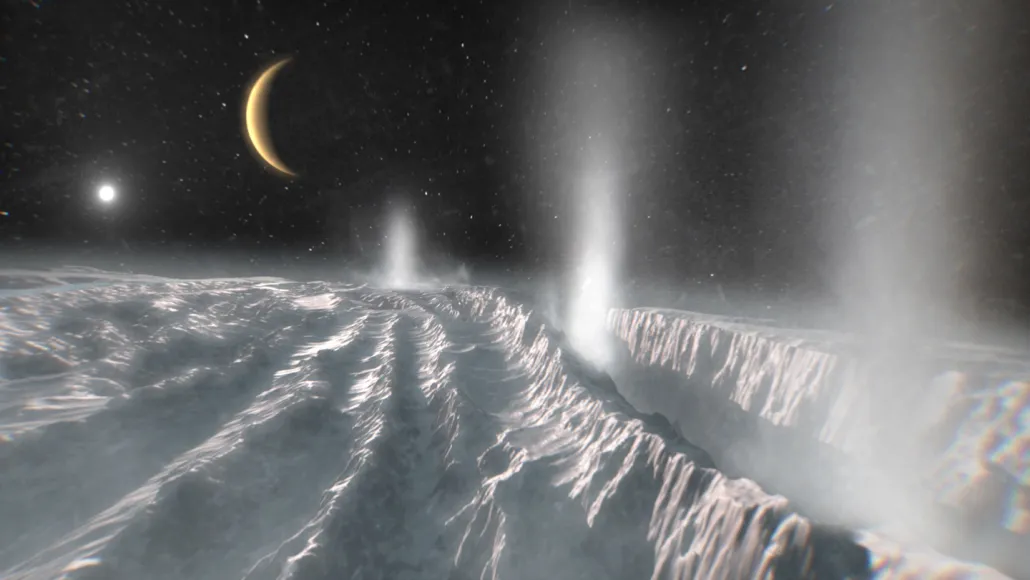

Enceladus’ ocean may not have produced precursor chemicals for life

The icy moon of Saturn is a contender for hosting life

Organic compounds spewed by Enceladus’ geysers (illustrated) may have formed above ground via radiation instead of within the moon’s subsurface ocean, a new study suggests.

ESA/Science Office