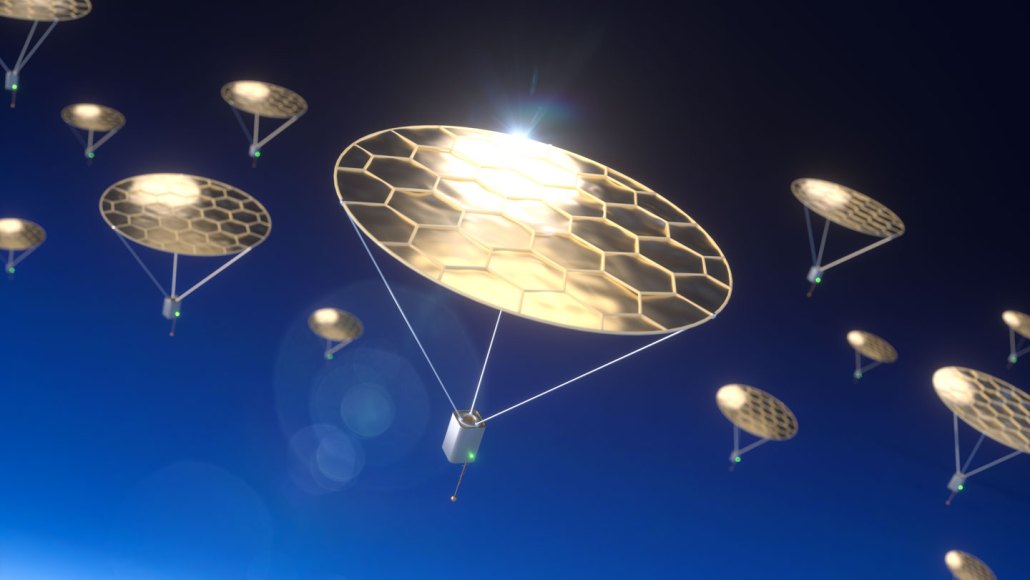

Lightweight aircraft could fly in Earth’s poorly understood mesosphere. The devices could carry payloads (illustrated) for weather measurements or communications networks.

B.C. Schafer et al/Nature 2025

Lightweight aircraft could fly in Earth’s poorly understood mesosphere. The devices could carry payloads (illustrated) for weather measurements or communications networks.

B.C. Schafer et al/Nature 2025