In the war of the WIMPs, a new combatant has joined the fray. The CRESST-II experiment has seen hints of the weakly interacting massive particles, a leading candidate for the hidden dark matter thought to account for most of the universe’s matter.

The new results, reported September 6 at the International Conference on Topics in Astroparticle and Underground Physics in Munich, add controversy to an already contentious field that is divided into two camps: those that have seen signs of the particles and those that haven’t.

“It’s another small victory for those arguing that this is dark matter, but it’s not going to decisively determine anything,” says theorist Dan Hooper of the University of Chicago and the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Ill. “We still haven’t seen a smoking gun.”

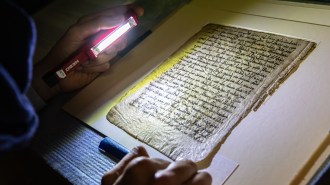

Housed in Italy’s Gran Sasso National Laboratory beneath the Apennine mountains, the CRESST-II dark matter detector is made of supercooled calcium tungstate crystals. When struck by incoming particles, nuclei inside the atoms of the crystals recoil. By measuring the light and heat given off by these collisions, scientists hope to distinguish potential WIMPs from other more common particles.

Between 2009 and 2011, the crystals produced 67 flashes that matched the expected WIMP signature. About half of these flashes can be explained by background contamination. A WIMP with a mass around 12 times that of a proton could explain the other half, but so could an unknown source of background contamination. Figuring out all the things that can trigger a flash in a dark matter detector is notoriously difficult, so the CRESST team is being cautious about claiming discovery.

“Because of background questions we are not now making a claim,” says Leo Stodolsky of the Max Planck Institute for Physics in Munich and a CRESST-II team member.

At the same meeting, researchers from the COGENT dark matter experiment in Minnesota reported sightings that could be consistent with the CRESST-II results, Hooper says. Interesting but inconclusive signs of WIMPs with masses between about 7 and 16 times that of a proton have turned up in COGENT’s germanium detector.

To further complicate the picture, though, these two experiments must be reconciled with results from the DAMA/LIBRA experiment. Its sodium iodide detector in Gran Sasso has found evidence for WIMPs that suggests slightly different properties for the particles than what’s been hinted at in the more recent work.

“I don’t think we know for sure exactly what is going on,” says Jodi Cooley, a particle physicist at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. “Based on the understanding we have of dark matter and how it behaves, I’m not sure how much agreement I would say that these experiments have.”

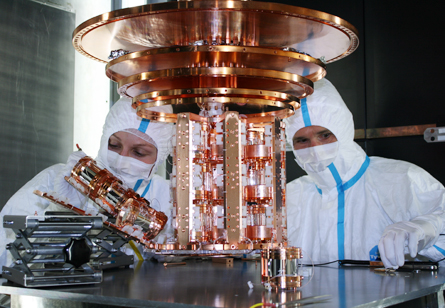

Cooley works on the CDMS II experiment in Minnesota’s Soudan mine, one of two detectors that have seen no signs of dark matter or its purported particles at all. XENON100, which searches for dark matter using a tank of noble gas in Gran Sasso, has ruled out all of the WIMPs proposed by CRESST-II and its compatriots.

“Their claims are incompatible with our results,” Antonio Melgarejo, a particle physicist at Columbia University and member of XENON100 team, says of the new findings.

To strengthen its case, the CRESST-II team is searching for ways to reduce the background noise in its equipment. But Melgarejo says that he’s looking to new detectors that could double check some of these controversial WIMP sightings to clear up the confusion — including a germanium device currently being tested at small scales in China’s JinPing underground laboratory.

Until then, the search for dark matter remains opaque.