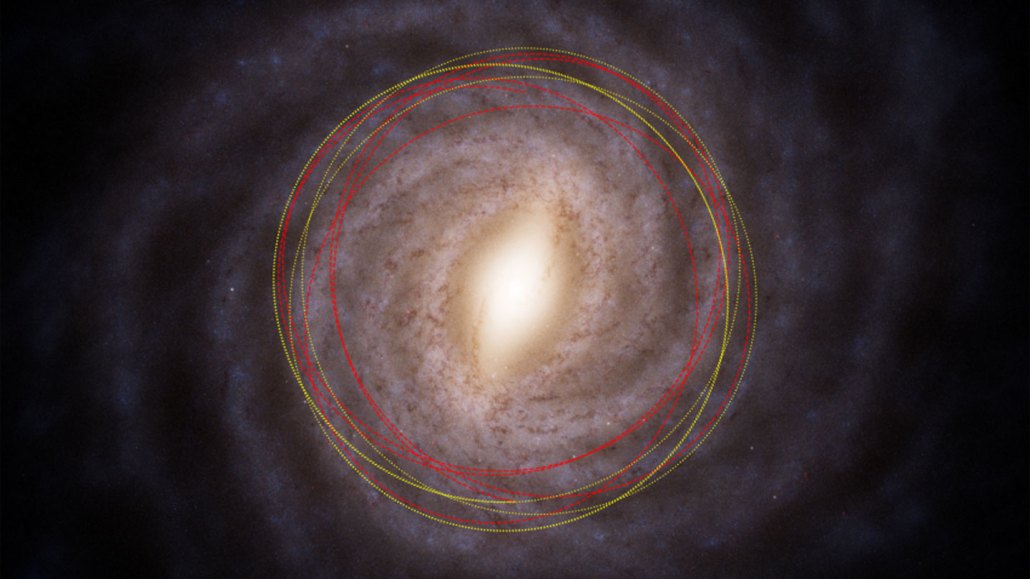

The interstellar object 3I/ATLAS may have come from the thick disk of the Milky Way. Its predicted orbit is shown in red dashed lines; the sun’s orbit is shown in yellow.

M. Hopkins/Ōtautahi-Oxford team. Base map: DPAC/Gaia/ESA, Stefan Payne-Wardenaar (CC-BY-SA 4.0)