A giant planet may orbit our closest sunlike neighbor

The Webb telescope spotted the planet candidate near Alpha Centauri A

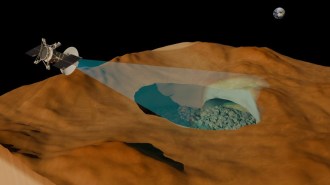

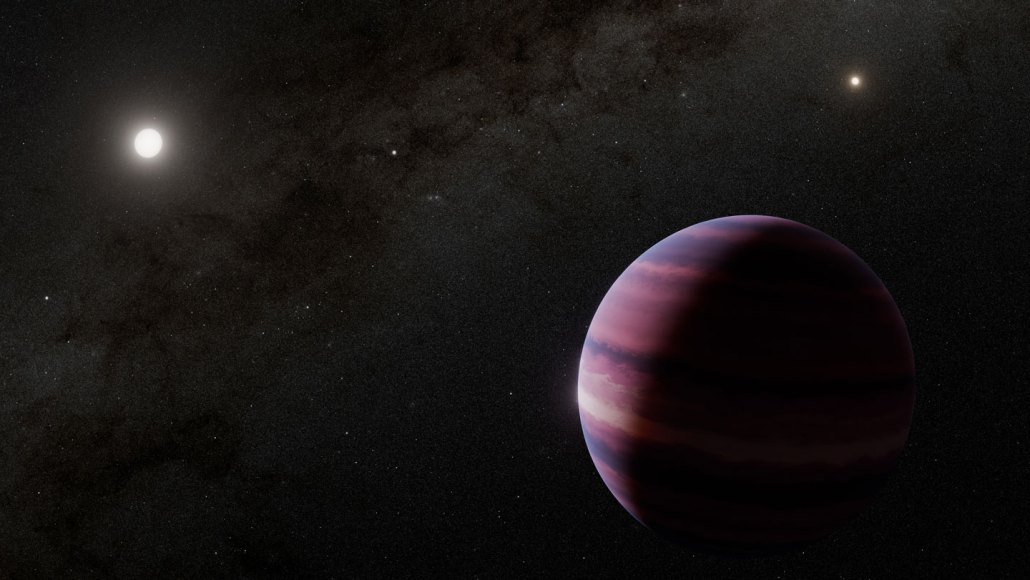

A gas giant (bottom right in this illustration) might orbit one of the solar system’s nearest sunlike stars, Alpha Centauri A (upper left). It’s part of a star system that includes another sunlike star, Alpha Centauri B (upper right).

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, R. Hurt (Caltech/IPAC)

A sunlike star next door called Alpha Centauri A may host a huge planet, researchers report in two studies in press in Astrophysical Journal Letters. The planet candidate orbits in its star’s habitable zone, where liquid water could exist on a body’s surface — although the object might be a gas giant that cannot support life.

At about 4.3 light-years from Earth, Alpha Centauri A and its sibling star Alpha Centauri B are the closest stellar neighbors that resemble the sun in mass, age and temperature. These dance partners orbit one another while a third star, the red dwarf Proxima Centauri, circles the pair from afar. Proxima Centauri is the only star that hosts confirmed planets within this three-star system.

Alpha Centauri A’s proximity to Earth makes it “an exceptional target for planet searches,” says Caltech astrophysicist Aniket Sanghi, who submitted the papers about the potential discovery to arXiv.org on August 5. But orbiting objects are hard to detect around the star. Nothing has been seen passing in front of it and dimming its starlight from the perspective of Earth or space telescopes. A newer search technique aims to directly image potential planets. But Alpha Centauri A’s light can outshine that from any orbiting companions, and the partner star’s glow interferes as well.

So Sanghi and colleagues used the James Webb Space Telescope to spy on Alpha Centauri A’s habitable zone in infrared light, since any cool planets there should strongly emit these wavelengths. In August 2024, JWST, which sees in a wider range of infrared light than past telescopes, snapped images while a coronagraph instrument blocked most of the host star’s light. A computer program later removed remaining glare from both sunlike stars.

The observations revealed a potential planet near Alpha Centauri A, at about twice the distance between Earth and the sun. Combining JWST’s view with older data from the Very Large Telescope in Chile helped the researchers estimate that the planet candidate travels an elliptical orbit, reaching roughly the distance between Earth and the sun at its closest point to the host star. They also calculated that the object has a mass comparable to that of Saturn and is similar in size to Jupiter.

That huge size hints that the purported planet might be a gas giant, whose atmosphere likely can’t support “life as we know it,” Sanghi says. Moreover, if confirmed, the big planet’s gravity would dominate Alpha Centauri A’s habitable zone, kicking out any Earthlike planets, “much like a bowling ball clears its pins.”

Two follow-up searches with JWST in 2025 failed to find the celestial body. That isn’t surprising, Sanghi says. Computer simulations suggested the object was at a point in its orbit where it was too close to the host star for JWST to see it during the later attempts. Sanghi and colleagues suspect that the planet candidate takes a two-year trip around Alpha Centauri A, so they plan to set JWST’s sights on it again in August 2026 to help verify its status.

While astrophysicist Eric Agol commends the team’s work, he remains cautious and emphasizes that it’s too early to call the object a planet. “I have seen planet candidates come and go,” says Agol, of the University of Washington in Seattle. But if validated, “this is the best case we have for detecting and characterizing a habitable-zone exoplanet around sunlike stars in our entire galaxy.”

The work represents a larger change in exoplanet searches and helps pass the torch to direct imaging, says MIT astrophysicist Sara Seager, who was not involved in the new studies. “I’m confident we’re going to look back in the future and say this was the start of a new era.”