The oceans’ good old days may have been even better than biologists thought.

That’s the picture emerging from an effort to reconstruct the history of marine populations using what environmental historian Poul Holm of Trinity College Dublin calls “eclectic methods.” Mining for data in old ships’ logs, tax records, travelers’ journals and even ancient Greek and Roman poetry is providing clues to the life of oceans past.

Holm chairs the historical arm of the Census of Marine Life, a 10-year international research collaboration due to publish a final report in 2010. Researchers trying to piece together glimpses of past ocean life are scheduled to convene for the Oceans Past Symposium in Vancouver, Canada, May 26 through 28.

“It’s a mix of gloom and doom, with a glimmer of hope,” Holm says. Work so far suggests that the upper layer of the oceans has lost 85 to 90 percent of the mammals, big fish and other fisheries species that swam there several hundred years ago.

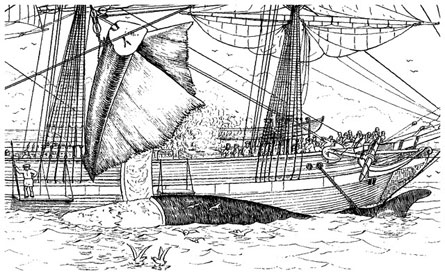

Big changes began during the days of sailing fleets. “The impact of these early fisheries could have been much larger than we would have thought 10 years ago,” Holm says. In Europe’s North Sea, low-tech vessels were catching about 300,000 tons of herring a year by 1870.

Coaxing back a population after intense fishing and hunting is possible, though, says marine ecologist Heike Lotze of Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada. For example, the fur trade had shrunk California’s sea otter population down to a few dozen individuals by the early 20th century, but numbers have now rebounded to some 2,000 animals, Lotze says.

As Holm puts it, visions of past abundance suggest that “the oceans actually used to have a much higher productivity than we ever used to think — that’s the glimmer of hope.” That potential, he contends, still exists.