Young pterosaurs probably died in violent Jurassic storms

Fossils from Germany suggest young flyers were felled by violent winds 150 million years ago

A Pterodactylus hatchling (illustrated) struggles to fly in powerful storm winds.

Rudolf Hima

The broken wings of two young pterosaurs may reveal how hundreds of their kind met their end about 150 million years ago.

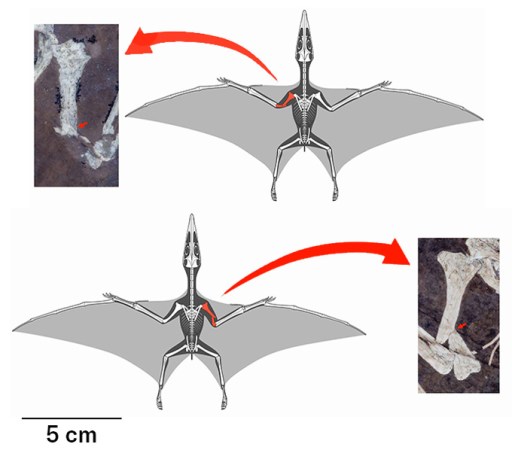

New analyses of the well-preserved, complete Pterodactylus fossils — dubbed “Lucky I” and “Lucky II” — show that a humerus bone in each hatchling had been cleanly fractured at an oblique angle. This indicates that their arms were wrenched in a powerful twisting motion, researchers report September 5 in Current Biology.

The culprit was probably a violent windstorm that proved too powerful for the young animals, say paleontologist Robert Smyth of the University of Leicester in England and his colleagues.

The mystery of the pterosaurs’ demise is a cold case going back about 150 million years, when much of what’s now Germany was covered by a warm, shallow sea. Coral reefs walled off parts of that sea into isolated lagoons with thick, soft, carbonate mud bottoms. Those muds created an excellent environment for fossilization, even of the fragile, lightweight bones of flying reptiles such as pterosaurs.

One such lagoon is now a limestone quarry filled with Jurassic Period fossils, including small dinosaurs and Archaeopteryx, the earliest known bird.

Known as the Solnhofen Limestone, this ancient graveyard is especially renowned for its abundance of pterosaur fossils — particularly those of hatchlings. These fossils are helping researchers better understand pterosaurs’ growth, paleoecology, and when and how they could fly.

Oddly, the site’s adult pterosaur fossils tend to be found in bits and pieces, while the specimens of the younger individuals are beautifully complete. That’s counterintuitive, because the hatchlings’ skeletons should be even more fragile than the older ones.

Violent storms could explain this mystery, the researchers say. The young pterosaurs probably struggled against the wind, ultimately falling into the lagoon, where they were drowned and quickly buried in the sediment, the team suggests.

Older pterosaurs, meanwhile, might have struggled mightily in both the storms and the lagoon before succumbing. Their carcasses may then have been tossed about in the water before sinking, resulting in more scattered bones.

The finding, the team notes, highlights how catastrophic storms can distort the fossil record by selectively preserving different specimens in different ways.