A new AI-based weather tool surpasses current forecasts

Aurora can be tweaked to predict air pollution, ocean waves, tropical cyclones and more

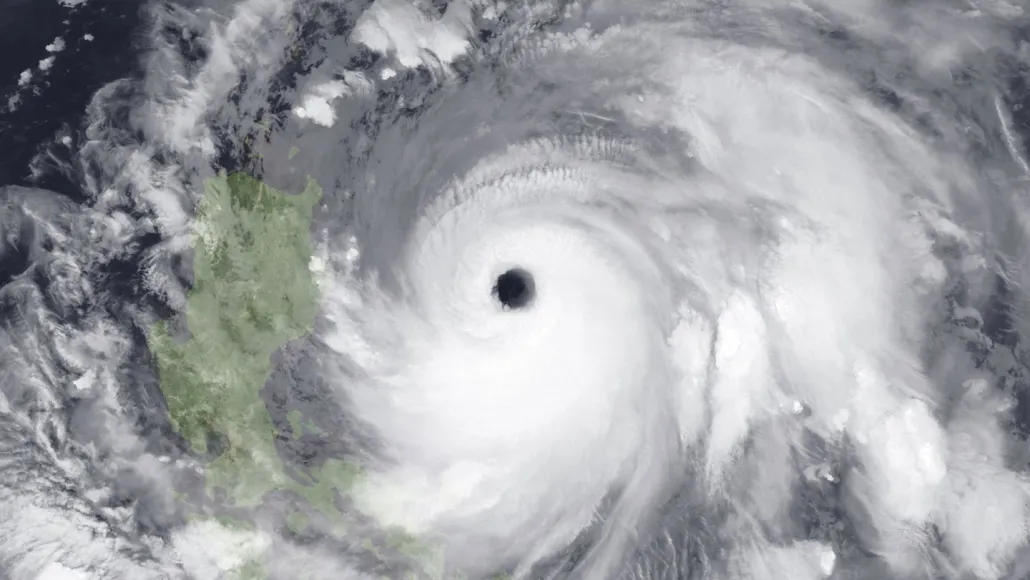

Typhoon Doksuri struck the Philippines in July 2023 and didn’t follow the predicted storm path. A new AI model called Aurora figured out the correct route from data captured four days in advance of the storm.

NASA

Weather forecasting is getting cheaper and more accurate. An AI model named Aurora used machine learning to outperform current weather prediction systems, researchers report May 21 in Nature.

Aurora could accurately predict tropical cyclone paths, air pollution and ocean waves, as well as global weather at the scale of towns or cities — offering up forecasts in a matter of seconds.

The fact that Aurora can make such high-resolution predictions using machine learning impressed Peter Dueben, who heads the Earth system modeling group at the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts in Bonn, Germany. “I think they have been the first to push that limit,” he says.

As climate change worsens, extreme weather strikes more often. “In a changing climate, the stakes for accurate Earth systems prediction could not be higher,” says study coauthor Paris Perdikaris, an engineer at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

And in recent months, the U.S. government has cut funding and fired staff at the National Weather Service, making it more difficult for this agency to get important warnings out in time.

Aurora is one in a series of machine learning models that have been steadily improving weather prediction since 2022, Dueben says. His group has used machine learning models similar to Aurora to provide forecasts for two years. “We’re running them every single day,” he says. Microsoft’s MSN Weather app already incorporates Aurora’s data into its forecasts.

Standard forecasting systems don’t use machine learning. They model Earth’s weather by solving complex math and physics equations to simulate how conditions will likely change over time.

But simulating a system as chaotic as the weather is an extremely difficult challenge. In July 2023, for example, official forecasts a few days in advance of Typhoon Doksuri got its path wrong. When the storm hit the Philippines, there was little warning. Dozens of people died in flooding, landslides and accidents.

In a test scenario, Aurora correctly predicted Typhoon Doksuri’s track from data collected four days in advance. The team looked at the tracks that seven major forecasting centers had forecasted for cyclones that took place in 2022 and 2023. For storms in the North Atlantic and East Pacific, the AI model’s predictions were 20 to 25 percent more accurate at lead times of two to five days.

Outperforming the official forecasts for cyclones at up to five days in advance “has never been done before,” says study coauthor Megan Stanley, a machine intelligence researcher based at Microsoft Research in Cambridge, England. “As we all know from many cases of typhoons and hurricanes, having even a day’s advance notice is enough to save a lot of lives,” she says.

Unlike standard forecasts, machine learning models don’t simulate physics and solve complex math formulas to make predictions. Instead, they analyze large datasets on how weather has changed over time. Aurora took in more than a million hours’ worth of information about Earth’s atmosphere. It learned how weather patterns tend to evolve. But that was just the start.

Aurora is a foundation model. In AI, a foundation model is sort of like a high school graduate. A new grad knows a lot of useful stuff already, but with some additional training, they could perform all sorts of different jobs. Similarly, a foundation model can go through a process called fine-tuning to learn to perform different kinds of specialized tasks. During Aurora’s fine-tuning, the team fed the model new kinds of data about different Earth systems, including cyclone tracks, air pollution and ocean waves.

The number-crunching for a physics-based weather forecasting model may take several hours on a supercomputer. And developing a new physics-based model takes “decades,” Dueben says. Developing Aurora took eight weeks.

Because models like Aurora can often be run on a typical desktop and don’t require a supercomputer, they could make powerful weather forecasting more accessible to people and places that can’t afford to run their own physics-based simulations.

And because Aurora is a foundation model that can be fine-tuned, it could potentially help with any kind of Earth forecasting. Stanley and her colleagues imagine fine-tuning the system to predict changes in sea ice, floods, wildfires and more.