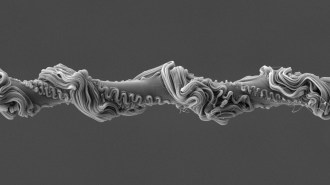

North Seymour island’s blue-footed boobies (shown) are popular with visitors to the Galápagos Islands. Monogamous pairs lay their eggs in open, poop-covered nests on the ground.

Erin Garcia de Jesús

As I step among poop-covered rocks toward the plateau of a small island in the Galápagos, a part of me rejoices. Not only am I about to see the archipelago’s famed blue-footed boobies for the first time, but the sight of guano everywhere, and birds to make fresh batches, serves as a reminder: The ongoing avian influenza outbreak has not yet ravaged this picturesque place.

Ghostly, leafless Palo Santo trees and saltbushes sprinkle the island, surrounded by boulders in varying shades of red-tinged black and brown. White splotches of guano splattered on rocks are hard to miss against this arid landscape on North Seymour Island in November, the tail end of the dry season. The poop’s sources are similarly difficult to overlook.

The island is known for hosting a large colony of magnificent frigatebirds (Fregata magnificens), some of which hang suspended in the air above tourists’ heads as we disembark from a dinghy and scramble up the rocky path. As I admire the birds’ fabulous red throat sacs — which males inflate like balloons to attract females — I hope that none deposit excrement on my head.

A short walk along a dusty trail brings us to, in my opinion, the stars of the show, blue-footed boobies (Sula nebouxii). The dopey looking birds show no sign of fear even as we cluster around their nests eagerly snapping photos.

That I had the chance to visit these birds on North Seymour at all — amid all their poop — was a relief after traveling more than 5,000 kilometers for a vacation in Galápagos National Park. Just two months before, at the end of September, news broke that deadly avian influenza had reached the archipelago.

The virus’ presence posed a grave threat. The islands are home to birds like the Galápagos penguin that are found nowhere else in the world. National park and government officials closed some islands to tourists to protect endemic seabirds — an understandable tactic that left me selfishly thinking about the possibility of not getting to see iconic birds up close. To track the virus, “we have eyes watching the whole archipelago,” wildlife veterinarian Gustavo Jiménez-Uzcátegui of the Charles Darwin Foundation told Science in September.

The concern is warranted. Outside the Galápagos, the global bird flu panzootic has been destructive. (Panzootics are the animal equivalent of human pandemics.) It’s unclear why the archipelago has so far escaped the worst of avian influenza, Jiménez-Uzcátegui told me when we met in the island town of Puerto Ayora. Also unknown are the effects the outbreak could permanently imprint on bird populations and the ecosystems that they’re a part of around the globe.

“Most people have no idea that we are in the middle of a wildlife emergency, an animal pandemic, and that this may be the nail in the coffin for some species,” says Michelle Wille a viral ecologist at the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Melbourne, Australia, who studies avian influenza. “It’s very concerning.”

Bird flu has killed millions of animals

While the viral variant behind the outbreak emerged in Europe in 2020, the outbreak itself didn’t take off until late 2021. Since then, avian flu has likely killed millions of wild birds (SN: 3/6/23). In Peru, hundreds of thousands of wild birds have died. Places like Russia and Canada have documented tens of thousands of deaths. In the United States, roughly 9,000 wild birds have tested positive for avian flu, some of which were reported after being killed by hunters.

In October, bird flu arrived in the Antarctic region for the first time when unexplained mortality of brown skuas on Bird Island was pinned on the virus.

But birds aren’t the only animals in the flu’s crosshairs. “If you can imagine thousands of dead birds, you can imagine how this is an ‘all day buffet’ for scavengers,” Wille says. Avian predators all over the world, including bears and foxes, have tested positive. Marine mammals such as seals and sea lions that swim with or eat infected birds have experienced mass die-offs. In the Arctic, a polar bear died in October after contracting the virus. And on January 11, researchers confirmed that elephant and fur seals in South Georgia, a sub-Antarctic island, had been infected.

By the time of my trip in mid-November, fears of birds dying en masse in the Galápagos hadn’t yet come to fruition. To date, there have been just 34 confirmed flu infections in red- and blue-footed boobies, Nazca boobies, frigatebirds and tropicbirds.

That the global outbreak is happening at all is a chapter in a predictable story, says Nichola Hill, a disease ecologist at the University of Massachusetts Boston. And the virus’s incursion into some mammals is “absolutely on track with being the worst-case scenario you could have imagined for this.”

The flu’s long-term effects remain unclear

Researchers have long understood that avian influenza viruses — which normally cause mild disease in waterfowl like ducks — can turn deadly after spreading and evolving on poultry farms (SN: 9/2/05). Close relatives of the virus responsible for the ongoing panzootic have been “simmering away” in Eurasia for more than a decade, Hill says. “And now in the last three years, it’s had major consequences for wildlife.”

For now, researchers are focused on documenting the sheer scale of avian and mammalian deaths. “We will probably not know the true extent of this for years to come,” Wille says. The ripple effects on ecosystems will likewise take years to unravel.

Death rates vary among bird species. Waterfowl such as ducks are key spreaders of bird flu and have at least some built-in protection from the virus. Because their immune systems have coevolved with influenza viruses, the animals have a “head-start on immunity” compared to other animals, Hill says. Meanwhile, birds like bald eagles and red-tailed hawks that don’t have such a long history with influenza are “just getting hit really hard.”

That disparity has Hill wondering how long it might take for infections to become less deadly, as wild birds develop immunity against the virus. Her lab aims to explore how birds’ immune systems have coevolved with avian flu, including which parts of the immune response are crucial for preventing the virus from running rampant and causing death in some species.

As of now, Wille says, there are no signs that the panzootic is slowing down. But there are glimmers of hope.

In October, researchers announced some early results from a bird flu vaccine trial in California condors. After 10 birds had received two doses of the vaccine, six of them had antibody levels high enough to provide at least partial protection against death. “If it works, it demonstrates that we may be able to limit the impact on highly endangered species,” Wille says.

Climate may be protecting the Galápagos

Why avian flu has been less “aggressive” in the Galápagos compared with most everywhere else — and whether it will stay that way — remains a big question, Jiménez-Uzcátegui says. But he has one intriguing hypothesis.

“The unique difference from the other parts [of South America], like Peru, Ecuador,” he says, “is the habitat.”

Flu in both people and birds tends to largely be a cold-season disease (SN: 1/11/23). Last year, El Niño arrived in the Galápagos, bringing warmer than average waters to the islands’ part of the Pacific Ocean. Normally, the climate pattern reduces the marine food supply, affecting many of the animals that swim in the waters around the islands. The more moderate temperatures may have also made it harder for avian flu to spread, Jiménez-Uzcátegui says.

Piecing together the relationship between the local climate and influenza infections could help determine if Jiménez-Uzcátegui’s hunch is correct. He and his team also hope to examine the immune systems and genetics of birds that call the archipelago home. For now, though, researchers and officials continue to keep an eye out for influenza on the islands.

On the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s easy to center humans in worries about infectious diseases, especially because influenza outbreaks can be devastating (SN: 10/27/21). But my visit to Galápagos National Park — a truly special place for nature lovers — underscored that wild birds around the globe are enduring the worst flu outbreak yet. And despite small signs of hope in these iconic islands, the virus’s impacts could reverberate for years to come.