Ssssurprise. Burmese pythons have specialized cells in their intestines that help gather up the calcium and phosphorus from the bones of their prey — cells that might be found in other animals that swallow their meals whole.

agus fitriyanto/Getty Images

Burmese pythons and other carnivorous snakes are well-known for swallowing their prey whole. But what comes out the other end doesn’t resemble what went in.

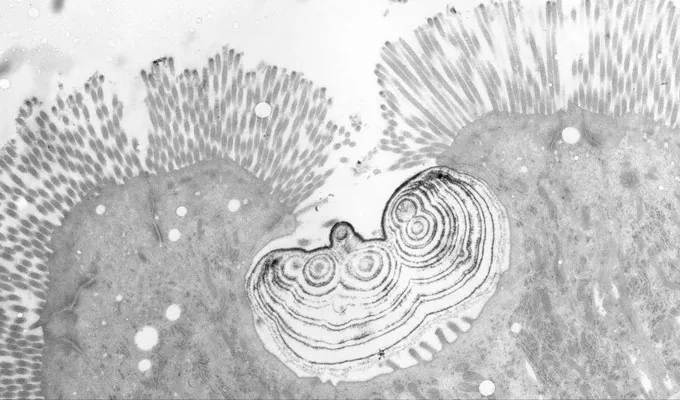

There’s not a bone to be seen in their poop. The secret? A specialized type of cell in the snake’s intestine that collects nuggets of calcium and phosphorus from the prey’s bones around an iron core, scientists reported in a paper published in the July Journal of Experimental Biology. These excess bits of ex-bone are then smoothly excreted.

Snakes like Burmese pythons (Python molurus bivittatus) are “intermittent feeders,” says Jehan-Hervé Lignot, an ecophysiologist at the University of Montpellier in France. “They are waiting for the food to pass in front of their nose.” They eat, then fast, going weeks or even months between meals. During their fasting periods, the snakes stop secreting digestive juices. The lining of their intestine atrophies, and even the cells with tiny fingerlike villi that would absorb nutrients in their guts shrink. The snakes’ stomach — which is highly acidic during digestion — sits at a nearly neutral pH.

But add a nice, tasty rat, and the system quickly hits high gear. The stomach pH drops to 2, and the microvilli grow to handle the sudden feast. “That was actually our initial question,” Lignot says. How can snakes “spend weeks, months without eating, and how they can change the gut lining so they can absorb all the nutrients” they need?

One of those nutrients is calcium. The snake’s highly acidic stomach wears away at even the enamel of an animal’s teeth. Without enough calcium in their diets, snakes’ health can suffer. Too much, though, can poison them, says Mike Cove, a conservation biologist at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences in Raleigh, N.C., who was not involved in the study.

To find out how exactly Burmese pythons control the amount of calcium hitting their systems during feeding, Lignot and his colleagues took 14 pythons and examined their intestines and blood. Some snakes were kept fasting, others received a rat. Still others received a deboned rat to examine the effects of low calcium, while a last group received deboned rat with added calcium.

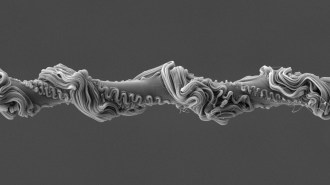

When the snakes were fed calcium-rich rat, the scientists observed a different kind of cell in their small intestines in between the villi absorbing nutrients. These cells, shaped like small cups, contained iron-rich particles. These particles collected concentric layers of the excess calcium and phosphorus from the snake’s meal much like a particle of dust collects bits of ice to form a snowflake. “I was looking at snake poo using the electron microscope,” Lignot says. “And it’s actually full of particles. So there’s a lot of calcium actually put away in the poo.”

The finding demonstrates how incredibly flexible the pythons are, Cove says. “No wonder they can literally digest anything.” He works on eradication of invasive Burmese pythons in the Florida Keys, and has seen partially digested skeletons in snake stomachs. On one partially digested raccoon jaw, he says, “you could just see where even the enamel’s all being eaten away.” Their specialized cells, he notes, could help snakes like pythons succeed when they are introduced to new environments like the Florida Everglades.

Burmese pythons aren’t the only animals with such bone-breaking skills. Lignot has since observed these same little cup-shaped cells in other snakes such as boas, and also alligators, even in Gila monsters (Heloderma suspectum). He suspects they are in other reptiles, such as green water snakes (Nerodia cyclopion) and sunbeam snakes (Xenopeltis unicolor), that swallow their prey whole. And “evolutionarily speaking, birds and these kind of reptiles are quite close,” he notes. Some vultures such as the bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus) also eat bones. “They are ideal candidates,” he says, to see if other groups of animals possess similar cells to control their calcium.