No, shaken baby syndrome has not been discredited

Despite what defense lawyers claim, the diagnosis is real, doctors say

Shaken baby syndrome is a form of child abuse that can cause lifelong injuries and disabilities or even death.

Pete Ryan

About five years ago, Nicole, a mother of two, had friends over for dinner while her husband, Sean, watched 3-year-old Courtney and 2-month-old Sarah. Fifteen minutes into dinner, Sean interrupted Nicole to ask for a pacifier and then interrupted again later because Sarah had pooped through her diaper and left a mess on the floor. After he took the baby to her room to change her, Sean called for Nicole again.

“I could tell something was wrong in his voice,” recalls Nicole, who is using only her middle name and pseudonyms for her family to protect their privacy.

Sarah was having a seizure and then went completely limp. Nicole and Sean called 911.

At the hospital, a CT scan revealed a large brain hemorrhage, and Sarah was airlifted to a children’s hospital. On the half-hour drive there, Nicole asked Sean what had happened.

“Courtney had been jumping on the couch and then hit Sarah on the head,” he told her. It had been an accident.

Sarah spent four days in the ICU, where she had hour-long seizures. Exams found severe brain swelling, injuries to her neck ligaments and significant bleeding behind the eyes called a retinal hemorrhage. But there was no evidence of blunt force trauma, as would be expected if Sarah had been hit on the head by her sister.

To put Sarah’s injuries in context, a pediatrician interviewed her parents at length about her medical history and the circumstances leading up to the injury. A few days later, a police detective requested an interview. When Sean left for the police station, he seemed nervous, Nicole says. It was the first indication to her that something was off.

A little while later, Sean called. He was crying. “I’m so sorry. I shook her. I shook her twice,” Nicole remembers him saying. “My whole heart just shattered like glass all over the floor,” she says. “I just felt like everything in our lives changed right there in that moment.”

Sarah was diagnosed with abusive head trauma, the medical name for shaken baby syndrome, which can be caused by shaking, an intentional impact against a surface, or both. Shaking is particularly dangerous for babies because of their relatively large head and weak neck muscles.

Each year in the United States, about 25 to 35 infants per 100,000 infants under 1 year old suffer abusive head trauma — about 1,300 babies a year — and 10 to 20 percent of them die. The most common injuries include brain and retinal hemorrhaging, brain swelling, neck-ligament injuries, difficulty breathing, rib or other bone fractures, and bruising on the torso, ear or neck. Roughly 80 percent of survivors experience lingering harms that can include learning disabilities, blindness, seizures, hearing or speech problems, and behavioral disorders.

Shaken baby syndrome was first described in 1971, when the medical understanding of child abuse was in its infancy. As research accrued, physicians and forensic pathologists fine-tuned the diagnostic process, which relies heavily on determining whether the physical injuries match caregivers’ descriptions of what happened. But in the early 2000s, doubt about the diagnosis crept into the legal system.

In 2009, the American Academy of Pediatrics, or AAP, updated the condition’s name to abusive head trauma to be more inclusive of cases where blunt force trauma may be present, with or without shaking. Some defense lawyers have argued that the change suggested a lack of scientific consensus over the cause of injuries typically associated with shaken baby syndrome. Although the name changed, the diagnostic process did not.

Yet today, when criminal cases land in court, defense attorneys often attack abusive head trauma as a “junk science,” no different than other debunked forensic fields like microscopic hair analysis and bite-mark comparisons. The Innocence Project, a nonprofit that works to overturn wrongful convictions, includes the diagnosis on its list of “misapplied forensic science.”

Doctors disagree. “The courtroom has become a forum for speculative theories that cannot be reconciled with generally accepted medical literature,” six radiology and pediatric medical groups noted in a 2018 consensus statement published in Pediatric Radiology and later endorsed by 11 additional medical organizations as of 2021. “There is no controversy concerning the medical validity of the existence of [abusive head trauma].”

And in February, a new AAP technical report laid out the extensive science supporting the diagnosis and described the complex process by which doctors diagnose it.

Today, the false narrative that the diagnosis is debunked and controversial continues to make headlines. That makes doctors concerned that the public will conclude that shaking an infant is not necessarily as harmful as claimed.

“I’m worried … that this effort to discredit the validity of the diagnosis is going to undermine efforts to keep children safe because shaking a baby is dangerous, and that’s a message that needs to be out there,” says Andrea Asnes, a child abuse pediatrician at Yale School of Medicine. Perpetuating the idea that it’s a disputed diagnosis, Asnes says, could make it harder for judges and other officials “to understand the degree of danger that a caregiving situation may pose for a specific child and limit their ability to keep the child safe.”

A diagnosis disputed in the courtroom

Most criticism of the abusive head trauma diagnosis centers on a collection of three signs dubbed “the triad” by defense teams: brain swelling, brain hemorrhaging and retinal hemorrhaging. Critics claim that physicians diagnose abusive head trauma based solely on the presence of the triad. Yet each of these injuries has many other possible causes, skeptics say, so the diagnosis is invalid because it’s not specific enough to eliminate all other possibilities.

But the triad is a straw man argument. “I’ve never used that term in all my life,” says John Leventhal, a child abuse pediatrician retired from Yale.

Those three injuries are indeed common in abusive head trauma — brain and retinal hemorrhaging are present in some 80 percent of cases, research shows — but diagnosis is much more involved.

Alleging that pediatricians rely solely on the triad “is clever in the sense that it sort of implies a rush to judgment, because it’s 1-2-3, done,” says Leigh Bishop, director of the Babies and Toddlers Task Force at the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner. “And any practicing, credible doctor in the hospital or forensic pathologist will tell you that these cases are the opposite of 1-2-3 and done. They require layers of medical investigation.”

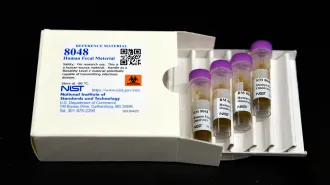

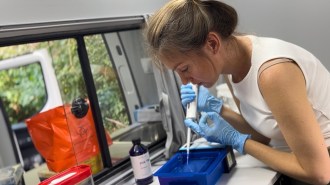

The new AAP report compiles decades of research on how to accurately diagnose abusive head trauma, reviewing the prevalence of different signs and symptoms. It describes the medical tests — blood tests, CT scans, MRIs and more — that can rule out alternative diagnoses, including infections, metabolic conditions and rare genetic bleeding disorders. The report also emphasizes the importance of the caregiver’s narrative of events in understanding the context in which the injury occurred.

When a clinician suspects abuse, a specialized child abuse pediatrician is called in. “We’re not only looking for specifically strong associated findings with inflicted trauma, but we’re trying to rule out other big things as well,” says Sandeep Narang, a child abuse pediatrician at Children’s Wisconsin hospital in Milwaukee and lead author of the AAP report. If trauma is the only reasonable cause of the injuries after ruling out other possibilities, the pediatrician, as part of a team of specialists, must determine if it’s accidental trauma, birth trauma or inflicted trauma.

Why shaking is dangerous

Babies are fragile. Their weak neck muscles can’t support the weight of their relatively large heads. So if a baby is shaken, the brain will move back and forth inside the skull. That can result in injuries such as:

- Bleeding in the brain and the retina — Violent motion can rupture blood vessels.

- Brain cell and spinal cord damage — Violent motion can cut connections between nerve cells. If the infant experiences difficulty breathing, a lack of oxygen can further harm nerve cells.

- Brain swelling

- Bone fractures and bruising

“Most of the trauma we evaluate is accidental, and it’s accompanied by an explanation that makes sense,” Asnes says. “We become concerned when kids present with trauma and there’s no explanation. We don’t start with a presupposition about what happened.”

If the child died, forensic pathologists use the same process in determining the cause of death. “You’re looking for something to explain the injury,” says James Gill, a forensic pathologist and the chief medical examiner for Connecticut. That means the narrative a caregiver gives is crucial. “When you have inconsistencies, an anatomic finding that doesn’t fit with the history,” he says, “that’s when it raises a red flag.”

Often in court, however, “this complex medical thought process gets oversimplified and misstated,” Narang says. And sometimes, defense attorneys go as far as providing invalid alternative explanations to discount the diagnosis.

Claims arose in the early 2000s that a lack of oxygen, including that caused by sudden intense coughing, could cause some of the signs seen with abusive head trauma. This notion was disproved with studies looking at internal injuries of near-drowning victims and children with temporary cardiac arrest, Narang says. In another instance, four medical defense experts put forth during a trial that if a baby coughed hard enough, brain vessels could rupture. That claim was based on their interpretation of one child’s injuries.

Another claim is that a brain bleed from abusive head trauma is actually “re-bleeding” in a child who had brain bleeding during birth. But such re-bleeding has never been described in the medical literature, says Christopher Greeley, a child abuse pediatrician at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Reopening of a wound from a previous traumatic brain injury can happen, he says, but that previous injury would usually have been documented in the child’s medical history.

“The vast majorities of defense experts will acknowledge the harms in shaking a baby, but then they’ll talk out the other side of their mouth and say that shaken baby syndrome is not a real thing,” Narang says. “There are a few who will admit that it’s a real thing and then create the framework that it’s too susceptible to error for us to be diagnosing.”

Heather Kirkwood, an attorney in Seattle who works pro bono on cases she believes to be wrongful convictions, acknowledges that shaking a baby can cause harm. But she says she would expect to see certain signs, like neck injuries. Kirkwood says that in the 100 cases that she has reviewed, those signs were not present. A small research study in 2009, however, identified it in 71 percent of victims, and the new AAP report notes that spinal cord injury occurs in 30 to 80 percent of cases.

A small minority of both defense experts and lawyers claim that shaking simply cannot cause the severe injuries seen in these cases. “There’s some people who just don’t believe it, and they will go to extraordinary lengths to try and explain it away somehow,” Gill says.

Russell Jones is a defense attorney in Milwaukee who has worked on a handful of shaken baby cases. He doesn’t question that shaking a baby vigorously enough could cause serious injury. “If you tell me I’ve never found an instance [of a] shaken baby ever,” he says, “I’d find that hard to be credible.” He says juries tend to see through expert witnesses who outright discredit abusive head trauma versus those who raise doubts about whether the evidence in a specific case supports the diagnosis. “I would say, generally, juries get it right,” Jones says.

Research backs that up. Narang led a study published in 2021 in Child Abuse & Neglect that reviewed all abusive head trauma convictions in the United States that had been appealed and ruled on by a judge from 2008 through 2018. Out of 1,431 cases, only 49, or 3 percent, were overturned. A little less than half of those, 20, were overturned on grounds related to medical evidence — a dozen of which were due to “controversy” over the diagnosis.

Long-term consequences

About 80 percent of infants who experience abusive head trauma suffer long-term disabilities such as:

- Cerebral palsy

- Paralysis

- Vision loss or blindness

- Intellectual disability

- Epilepsy

- Seizures

But when the overturned cases were retried, nearly 42 percent of the defendants either pleaded guilty or were convicted again.

The notion that the diagnosis is controversial and discredited is so pervasive that the National Center for Prosecution of Child Abuse outlines nine common defense claims — such as the ideas that shaking alone cannot cause massive brain injuries — and how prosecutors can address them.

The scientific evidence for shaken baby syndrome

The ways in which critics have tried to discredit abusive head trauma mirror the tactics of skeptics who question human-caused climate change or the safety and efficacy of vaccines, Greeley says. These include the use of fake experts (ones who lack experience in child abuse or even pediatrics) and expectations of 100 percent certainty (demanding eyewitnesses or filmed proof of abuse). Another tactic is cherry-picking data.

Greeley points to a 2016 review by a Swedish government agency that concluded “there is limited scientific evidence that the triad and therefore its components can be associated with traumatic shaking.” The authors excluded studies with children who had any other abusive injuries, such as fractures, except pure “triad” cases, which are very rare.

“It’s really poorly done,” Greeley says of the review. Its methodology has been critiqued as so flawed that some physicians and researchers have called for its withdrawal.

One argument made by critics that has some merit, Greeley says, is that some early studies of abusive head trauma relied on circular logic. Doctors diagnosed patients based partly on the presence of certain physical signs, and then researchers pointed to those cases as evidence of what the physical signs of abusive head trauma are.

More recent research has minimized potential circularity. A 2019 study, for example, started with determining whether abusive head trauma occurred in 500 cases based only on the caregiver’s description of what happened, independent of physical injuries except for the presence of patterned bruising, abdominal injury or burns. The researchers then compared the injuries and symptoms in those cases to see which ones occurred most often in abusive cases versus nonabusive head injury or undetermined cases.

If only the triad symptoms were present, the likelihood that the case was abuse was a little less than 75 percent. But the likelihood rose to well over 90 percent with the presence of six to seven specific medical injuries.

A crying baby

Many cases of shaken baby syndrome occur when a caregiver becomes frustrated with a crying infant. Experts offer these tips when a little one seems inconsolable.

Take a deep breath

Count to 10 to calm down. Turn the lights down.

Leave the room

Place the baby in a safe spot, like an empty crib, and take a break. Check on the infant in 10 minutes. Many crying babies eventually fall asleep

Phone a friend

Call a friend or family member for emotional support.

Call the doctor

Contact a pediatrician if the baby has a fever or other symptoms of an illness.

The strongest indication of abuse, with nearly 100 percent likelihood, included six physical signs — difficulty breathing at home, brain hemorrhage, a bone fracture, retinal hemorrhage, brain swelling, and bruising of the torso, ears or neck — but with no skull fracture.

That a skull fracture is not a strong predictor for abusive head trauma is key, Greeley says, because signs like internal brain and retinal bleeding without a skull fracture suggest an infant’s injury was caused by forceful movement like shaking, instead of an impact against something, like falling onto the floor.

Researchers have also validated the abusive head trauma diagnosis by studying cases in which the caregiver admitted to shaking the baby. Although some critics question the reliability of these studies because police confessions can be coerced, in some 15 percent of cases caregivers voluntarily describe the act to health care providers, research shows. An understanding of injury patterns has also come from cases where someone witnessed the shaking.

Studies of bruising patterns have led to clinical tools that also help contribute to accurate diagnosis. TEN-4-FACESp is one such tool and was validated in a 2021 study with more than 2,000 children. If clinicians see certain kinds of bruising, it raises the suspicion of abuse. That’s what the acronym stands for: bruising on the torso, ears, neck, frenulum (the tissue that joins the upper lip to the gum), angle of jaw (jawbone under the ear), cheeks, eyelids, subconjunctivae (broken blood vessels in the eyes), any bruising on children under 4 months old, or patterned bruising (such as in the shape of a handprint).

Tools like TEN-4-FACESp do not mean certain bruises are automatically classified as abuse — pediatricians still must consider the history and eliminate other possibilities. But they are an important part of the process, with accuracy rates on par with many lab tests used in screening for diseases.

Shaking causes real harm

No one, including all the child abuse pediatricians interviewed for this article, has claimed that there has never been a wrongful conviction of shaken baby syndrome. That happens with any type of crime.

“Are there cases in the past where the science was wrongly applied? I’m sure there are, but [critics are] using that to discredit the entire diagnosis,” Asnes says. “People misdiagnose appendicitis, and there are people who have appendectomies when they do not actually have an inflamed appendix. Does that mean appendicitis doesn’t exist?”

When Nicole hears the claim that shaking can’t harm an infant, she says it compounds the trauma she’s already experienced. Although Sarah survived her injuries, she has needed physical and occupational therapy to overcome difficulty swallowing, a dragging foot and other challenges. “Her milestones are going to be harder to reach as she gets older,” Nicole says. Nicole and Sean are now divorced. Sean ultimately pleaded guilty to a Class A misdemeanor, with six days in jail and some community service.

Nicole shares her story to counter the narrative that shaken baby syndrome is somehow debunked. “If anyone who is trying to explain it away as a random, spontaneous medical anomaly had to watch their own baby go through uncontrollable, nonstop seizures and have to wonder every hour, for days, whether or not their child was going to be alive,” she says, “then I believe those people would stop talking about this nonsense.”