As they barreled across the desert toward Baghdad during the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq last March, the tanks, trucks, and armored personnel carriers churned up huge clouds of dust. Iraqi vehicles mobilized to defend against the onslaught generated their own plumes of grit. In a literal sense at least, much of the dust in Iraq has begun to settle. If history is a guide, however, the ruts the combat vehicles left behind will spew prodigious amounts of dust for years. That airborne material can cause major environmental and health problems.

As the battalions maneuvered across the arid terrain, their vehicles often broke through a delicate crust known as desert pavement. This type of veneer covers as much as half of the world’s arid lands. Despite the connotations of its name, desert pavement isn’t robust. It’s merely a thin shell of stones that lies atop the dust, soil, or sand. Multi-ton tanks easily breach these fragile mosaics, but so do dirt bikes and all-terrain vehicles. Even trudging hikers, grazing animals, and the scrabbling of rodents and birds can disrupt desert pavements, exposing subsurface material to erosion and disrupting fragile ecosystems of fungi and algae.

Damage can happen in a moment, but the processes that sculpt desert pavement typically act slowly, taking centuries to generate a surface resistant to wind erosion. Therefore, when desert pavements and their biota are wounded by human activity, it will take human action to heal them on a shorter timescale.

Scientists are currently developing large-scale experiments to determine what methods might be most effective for mending a scarred desert. Successful techniques, far from being of interest only in war-torn regions, might also address a plague of problems that could result from an increase in the recreational use of environmentally sensitive public lands in the American Southwest.

Back to the future

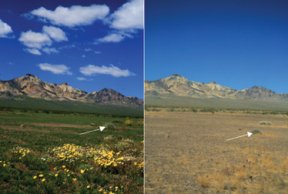

In August 1990, Iraqi troops invaded and captured Kuwait. For the next 6 months, they dug pits in the desert to hide equipment, excavated trenches to protect soldiers, and built 2-meter-tall sand berms to slow opposing troops. Military maneuvers during the liberation of Kuwait in February 1991 scarred the desert further. A comparison of satellite images taken just before and after the conflict show that almost 950 square kilometers of desert pavement were destroyed by such activity, says Farouk El-Baz, a geologist at Boston University. The planting or removal of land mines denuded another 3,500 km2 or so. In all, the desert pavement across more than 20 percent of Kuwait’s land area was disrupted.

As a result, immense quantities of the area’s fine-grained soil, previously locked beneath a stony blanket, were lofted by winds. Airborne dust reduced visibility and exacerbated a variety of health problems, such as asthma and other respiratory ailments, says El-Baz. Within months, the fine sands accumulated in dune fields on the northern shore of Kuwait Bay. In western portions of the country, sheets of sand smothered some roads and farms.

All that material had been brought to the area over the eons by the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, says El-Baz. Water flow in the rivers decreased when the region’s climate changed about 5,000 years ago and wind began to winnow the river delta’s dried sediments. Dust and sand in the upper layers of sediment were blown elsewhere, but gravel and pebbles were left behind and eventually compacted into a thin armor against further wind erosion.

With today’s drier climate in Kuwait and southern Iraq, it would probably take millennia for the wind alone to resculpt a fully mature desert pavement over the regions damaged by this year’s conflict in Iraq, says El-Baz. Restoration of the landscape to its original flat contours would probably limit erosion, minimize health problems related to dust, and decrease the amount of time needed to regenerate the war-torn desert pavement, he notes.

However, El-Baz doesn’t hold much hope for the war-torn soils of Iraq. “Everybody’s thinking about the security of the soldiers there, and rightly so,” he notes. “Nobody’s even thinking about the security of the soil.”

Floating rocks

Although the initial phases of a desert pavement’s formation are characterized by the wind-driven removal of surface dust and sand, other factors sculpt the rocky shell.

When the surface of nascent desert pavement becomes rough enough to interfere with airflow, small, windborne particles can drop out of that slow-moving boundary layer and fall between the cracks of the pavement’s stone mosaic. The trapped dust can even work its way underneath heavy pebbles, says Peter K. Haff, a geologist at Duke University in Durham, N.C. Any force that jostles surface pebbles—the impact of raindrops or the expansion and contraction of clay particles in the soil as they absorb and release moisture, for instance—can make the stones ride up on smaller particles that have recently fallen.

Even the footfalls of tiny animals can do the trick, says Haff. He once conducted an informal experiment in a terrarium on his desk, in which he placed a mixture of stones, pebbles, sand, and a few desert beetles large enough to budge marble-size stones as they propelled themselves across the ground.

Every few days, Haff scattered a little more sand in the terrarium. After a year, he’d added enough sand to create a layer 15 centimeters thick. The largest rocks remained buried at the bottom of the terrarium, and the smallest pebbles mixed throughout the sand. But a significant fraction of the medium-size stones—those measuring between 3 millimeters and 15 mm across—floated atop the steadily accumulating sand base.

Similar jostling of small stones across the surface of the ground can play a part in healing damaged desert pavements. In small-scale field experiments begun in 1983, Haff and his colleagues removed all surface stones from square patches of various sizes in the Mojave Desert. Over time, they noticed that surface pebbles 1 cm in diameter or smaller began to migrate into the vacant patches from surrounding areas. After a decade, the researchers’ 10-cm-by-10-cm patches had repaved themselves, but the 20-cm and 40-cm plots weren’t yet covered by the itinerant stones.

Haff estimates that it would take 50 years for such pavementfree plots to mend.

That’s a sluggish pace of renewal. If increasing human activity in these regions damages enough desert pavement, a plague of dust could result.

Two-tone stones

Many rocks in arid areas sport desert varnish, a dark, shiny coating rich in iron oxides and manganese oxide. Although scientists debate how this natural glaze forms, they generally agree that the process takes a long time. Many petroglyphs left by ancient cultures were created when artists scraped away areas of dark desert varnish and exposed the lighter rock beneath. In some cases, desert varnish hasn’t begun to form on the exposed rock, even though the petroglyphs were created millennia ago.

One testament to the age and stability of some desert pavements is the desert varnish that coats only the upward-facing exposed surfaces of the pebbles. While the rocks’ sunny sides are dark and manganese rich, their ground-facing surfaces are often stained orange by iron oxides in the soil. That two-tone coloration enables scientists to recognize whether a desert pavement has been recently disturbed, says Haff.

In California’s Greenwater Valley, just east of Death Valley National Park, much of the terrain is covered with a closely packed desert pavement that appears to have been undisturbed for centuries.

In April 1998, after the El Niño climate phenomenon steered above-average rainfall to Greenwater Valley, the normally barren desert pavement became carpeted with short grasses and wildflowers. The following April, after a climatically normal year, that living vegetation had nearly disappeared, Haff says. He also noted broad patches of pavement, ranging from small patches to areas half the size of a football field, where as many as 40 percent of the palm-size stones had been overturned to now sit orange-side up. Only 10 percent of such stones on nearby areas that had been more sparsely vegetated had been turned over.

What made the stones turn? The roots of the grasses and wildflowers that had grown in the cracks of the pavement weren’t strong enough to flip the stones, even if the vegetation were uprooted by strong wind, Haff argues. Human activity probably wasn’t the culprit because the valley lies in a remote area and there weren’t any footprints, vehicle tracks, or campfire remains.

Instead, Haff suspects, the stones had been flipped by rodents or birds rummaging for roots or seeds. In one instance, Haff observed a flock of more than 100 birds foraging among the dead weeds and later found a significant number of overturned rocks there.

If widespread enough, such disruptions of desert pavement could serve as long-lasting signs of even brief ecological changes, suggests Haff. Although the vegetation that triggered the purported feeding frenzies in the Greenwater Valley’s desert pavements was ephemeral, the effects of foraging on the desert pavement have lingered much longer.

Tanks, a lot

The suddenly mobilized sand and dust that plagued Kuwait after the war 12 years ago—and still blot the landscape there today—were unleashed during a mere 6 months of military maneuvers. Now, imagine the dust that winds could loft from the U.S. Army’s National Training Center, Fort Irwin’s Rhode Island-size facility in the heart of the Mojave Desert in southern California. Ten months each year, the center hosts war games and other exercises involving heavy-infantry vehicles.

In places, a few decades of traffic have pounded the training center’s grounds into a fine silt, just as if it had been exposed to centuries of natural weathering, says Jayne Belnap, a research ecologist at the U.S. Geological Survey in Moab, Utah. A lot of that loose material, which is calf-deep in spots, gets kicked up as dust. Elsewhere in the center, the soil has been packed to the point that rainfall doesn’t infiltrate the surface, which increases runoff there and erosion from unpacked soils nearby. Also, the roots of desert plants often can’t penetrate packed soils, and the plants therefore are slow to repopulate such areas.

The center is “like Kuwait on steroids,” says Robert H. Webb, a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Tucson. In severely compacted areas, it could take a century or so for natural geological processes, such as the expansion and contraction of clays, to restore just the upper 6 cm of soil to its previous consistency.

USGS studies of tank tracks at other Mojave Desert training areas used in the 1940s show that, even after more than 5 decades, soil density beneath the rut made by the single pass of a military tank is up to 6 percent higher than it is at a similar depth beneath undisturbed surfaces nearby. That difference may seem small, but investigators found that water seeps into the ground in the old tank tracks only half as quickly, on average, as it does into untouched soil.

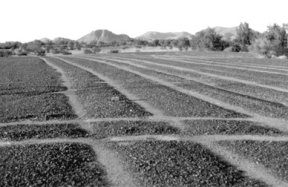

With large-scale field experiments, scientists might determine which restoration practices are effective, says Eric V. McDonald of the Desert Research Institute in Reno, Nev. He is now in the early stages of designing potential restoration projects for two Fort Irwin sites, each about the area of nine football fields. At one site, where recently disrupted desert pavement had been in place for the past 10,000 years, researchers will look for inexpensive ways to repair damaged portions of the surface, restore the vegetation, and perhaps recapture many of the original soil characteristics. Sensors embedded in the soil beneath revamped surfaces should reveal whether the temperature and soil moisture content there match those beneath pristine pavements nearby.

At another Fort Irwin site, a low-lying area where the desert pavement isn’t yet fully formed, scientists will probably look at a different set of techniques, says McDonald. One possibility is to deposit a gravel veneer and spray on chemical treatments that penetrate several centimeters into the ground and bind soil particles together. Such treatments sometimes are used to control dust at construction sites and on unpaved roads.

In field trials that McDonald hopes to implement at a military test site in Arizona, he would apply various combinations of added gravel, soil binders, and other treatments to small plots. Results from these experiments could guide efforts to create new desert pavements at the Fort Irwin sites, he notes.

This proposed research might reveal that it’s impossible to artificially restore desert pavement, says McDonald, “but at least we’d be looking at [the issue] in a scientific way.”

The results of these inquiries could affect more than distant war-torn lands and military training grounds here at home. Even four-wheel-drive pickups driven by weekend thrill seekers can wreak desert havoc. Although lighter than tanks, the trucks exert about four times as much pavement-busting pressure on the ground as tanks do, because the area truck tires occupy is much smaller than the footprint of a tank tread. That means the actual pressure per given patch of ground is higher for the smaller vehicles.

The burgeoning populations of large cities throughout the U.S. Southwest are venturing into arid, environmentally sensitive lands in ever-increasing numbers, McDonald notes. Regardless of whether those folks cross the desert in four-wheel-drive trucks, dune buggies, or hiking boots, they typically don’t tread lightly enough to leave desert pavement intact. If they’re not careful, they could churn up dust that could make life downwind miserable for generations.

****************

If you have a comment on this article that you would like considered for publication in Science News, send it to editors@sciencenews.org. Please include your name and location.