A Titan collision may link Saturn’s tilt, its moon Hyperion and its rings

The collision could also help explain why Saturn fell out of sync with Neptune

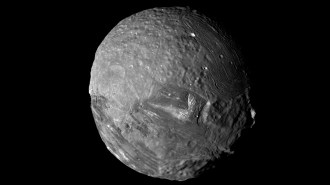

Saturn’s odd moon Hyperion, photographed by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft in 2005, could be debris from a long-ago moon smashup.

JPL-Caltech/NASA, Space Science Institute

Two of Saturn’s satellites — its largest and one of its weirdest — may owe their current forms and orbits to a two-moon pileup about 400 million years ago.

A smashup between a doomed moon and the massive moon Titan could have birthed the spongy-looking Hyperion, a study submitted February 9 to arXiv.org suggests. Ensuing chaos in the Saturn system could then have led to the formation of its rings.

The notion builds on a 2022 proposal by another team, which suggested the existence of a former moon to solve some long-standing mysteries about the Saturn system, including its relatively high tilt, its youthful rings and the orbital relationships of some of its moons.

The first clues came from Saturn’s relationship with Neptune. For decades, planetary scientists assumed that Saturn and Neptune had what’s called a spin-orbit resonance: Both Saturn’s spin axis and Neptune’s orbit around the sun seemed to wobble at almost the same rate. But data from NASA’s Cassini mission, which orbited Saturn from 2004 to 2017, showed that Saturn is slightly out of sync with Neptune. Still, the wobble rates are close enough to suggest the planets annulled their resonance relationship relatively recently in cosmic terms — maybe a few hundred million years ago.

“That tells us there was some disruption in the outer Saturn system,” says planetary scientist Matija Ćuk of the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif.

Ćuk and his colleagues suggest this disruption came in two parts. First, a doomed moon collided with Titan, altering Titan’s tug on Saturn’s spin axis enough to break the resonance with Neptune and producing debris that could later coalesce to form Hyperion. That collision might also have left Titan on a more extreme orbit — one that continued to slowly widen over the following few hundred million years. Titan’s orbital evolution eventually could have gravitationally triggered a slow-motion train wreck that led Saturn’s inner moons to collide and grind each other down, ultimately spawning both the rings and a new crop of young inner moons.

Previously, MIT planetary scientist Jack Wisdom and colleagues suggested that the break in Saturn-Neptune relationship coincided with the formation of Saturn’s famed rings, which some planetary scientists think are a mere 150 million years old. Wisdom’s team proposed that an extra moon, dubbed Chrysalis, could have tugged on Saturn’s spin axis, breaking the resonance with Neptune, before veering perilously close to the planet and being shredded into the rings.

“Jack wanted to tie those two together,” Ćuk says. “But I thought that the formation of Hyperion is a more direct clue.” Based on earlier work, Ćuk calculated that Hyperion must have settled into its current orbital arrangement within the last 400 million years, a timeframe comparable to that of the presumed dissolution of Saturn and Neptune’s resonance.

In the new work, Ćuk and his colleagues suggest that Saturn once had an extra moon, which they dub proto-Hyperion, about four times as massive as Chrysalis. Through computer simulations of a collision between proto-Hyperion and Titan, the team found that Titan survives, while some of the collision debris accretes into the present-day Hyperion, a porous, egg-shaped body that tumbles chaotically through space.

But without Chrysalis, the rings must have had a different origin, Ćuk says. His team suggests that Titan and Hyperion might explain this as well — if there were more missing moons. They posit that Saturn may have originally had several inner moons more massive than those present today. Titan’s altered orbit after the collision could, over hundreds of millions of years, put it in resonance with one of those inner moons, tweaking that moon’s orbit until it collided with another.

Wisdom doesn’t think Ćuk’s scenario quite works. For one thing, it would require the inner moons to all be younger than a few hundred million years old. But Mimas, one of those moons, has enough craters to suggest it is much older.

“Their arguments don’t invalidate our scenario,” he says, adding that the new proposal is “a very different, more complicated scenario.”

Ćuk thinks Mimas could still be young — its craters may have formed relatively quickly in the chaotic inner Saturn system. Both planetary scientists agree that more detailed simulations of the Saturn system are needed to show which picture is most plausible.

“There might be a third variant of instability that combines mine and Jack’s,” Ćuk says — or something new.