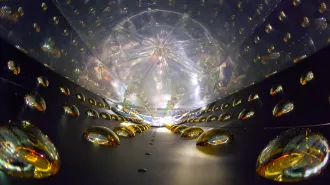

ON THE HUNT Astronomers are using the Very Large Array of radio telescopes in New Mexico to look for big black holes in small galaxies.

NRAO, AUI, NSF, Jeff Hellerman

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Big galaxies like the Milky Way have correspondingly big black holes. But small galaxies might have massive ones, too. A new survey picked up dozens of massive black hole candidates in diminutive dwarf galaxies.

Surprisingly, some of those potential black holes aren’t at their galaxy’s center, but instead appear to roam the outskirts, astronomer Amy Reines said May 20 at the Black Hole Initiative Conference 2019 at Harvard University. Studying these wonky monsters could help astronomers figure out the mystery of how supermassive black holes in bigger galaxies form.

“Contrary to conventional wisdom, dwarf galaxies can, and at least some do, have massive black holes,” said Reines, of Montana State University in Bozeman. These black holes could “hold clues to the formation of the first black hole seeds in the early universe.”

Almost every massive galaxy ever observed has a supermassive black hole at its center. These behemoths, including the Milky Way’s, weigh between 100,000 and a few billion times the mass of the sun. And that mass is closely related to the mass of the host galaxy. “In general, bigger galaxies have bigger black holes,” Reines said.

So when Reines, as a graduate student in 2011, stumbled upon a supermassive black hole in the dwarf galaxy Henize 2-10, she was stunned. Reines had been looking for signs of star formation, and instead found the actively feeding black hole, some 30 million light-years from Earth.

“This discovery marked a whole new environment for a massive black hole, and I was motivated to look for more objects like this,” she said.

Peering into thousands of dwarf galaxies, Reines and colleagues have since found roughly 100 massive black holes, given away by the glowing disks of gas that swirl around the black holes as they feed.

Those black holes “are likely the tip of the iceberg,” Reines said. Only the most actively feeding black holes show up in visible wavelengths, and only in galaxies with relatively low star formation. So there may be many others that are harder to spot.

The researchers are now focusing their search on longer, invisible radio wavelengths, which can reveal black holes that feed less aggressively. Using the Very Large Array of radio telescopes in New Mexico, the team has already found 39 possible black holes in 111 dwarf galaxies. At least 14 of those candidates are likely to be black holes, Reines said. Some of the others might be other objects that emit brightly glowing radio waves, such as supernova remnants.

Weirdly, some of the newly found black holes are not at their galactic centers, but instead are “wandering around in the outskirts of their host galaxies,” Reines said. Computer simulations had suggested that up to half of all dwarf galaxies might have off-center black holes. Still, “I was very surprised” by the finds, she said. “This hasn’t been seen before.” She suggested that the black holes could have been knocked askew in a galaxy merger, or kicked off-center when two smaller black holes merged within a galaxy (SN: 4/29/17, p. 16).

The work “identifies a new and unique population [of black holes] that may have been missed by other selection techniques,” says astrophysicist Vivienne Baldassare of Yale University, who uses other techniques to search for black holes in dwarf galaxies.

Studying massive black holes in small galaxies could help scientists figure out how supermassive black holes in larger galaxies got so big over cosmic time. One possibility is that black holes bulk up by adding their masses together when their host galaxies merge, or they could have started out relatively massive long ago (SN Online: 3/16/18). Dwarf galaxies, which are small enough that they probably haven’t gone through many mergers, may preserve relics of those ancient massive black holes. Knowing how big those relic black holes can get could help link up the supermassive monsters astronomers see in the present-day universe with their ancient counterparts.