Teens born from assisted pregnancies may have higher blood pressure

Reproductive technologies such as in vitro fertilization may put kids at risk of hypertension

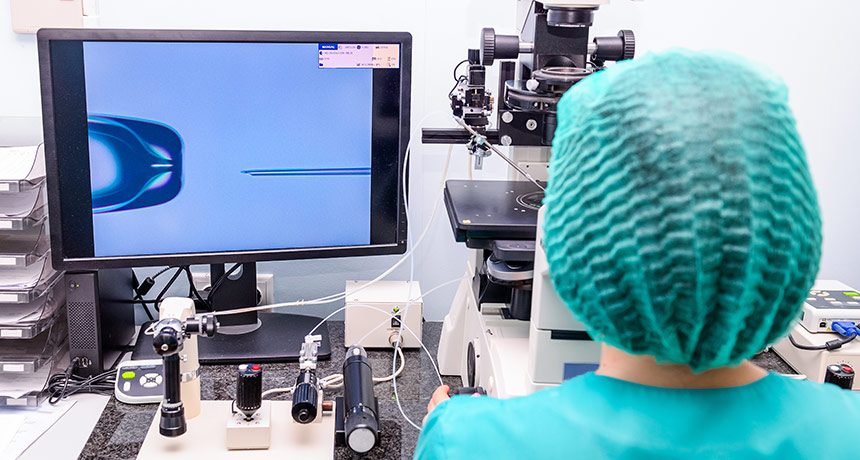

AN ASSIST Lab-conducted in vitro fertilization procedures, as well as other assisted reproductive technologies, may increase the risk of hypertension in teens conceived with such help.

Okrasyuk/Shutterstock

- More than 2 years ago

Assisted pregnancies give infertile couples the chance at a child. But kids conceived with reproductive technologies, such as in vitro fertilization, or IVF, were more likely to develop high blood pressure as adolescents than their naturally conceived counterparts, a new study finds.

Of 52 teens conceived with technological help, eight had hypertension, defined as blood pressure greater than 130/80 millimeters of mercury. Only one teen of 43 conceived naturally had the same high blood pressure, researchers report online September 3 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. High blood pressure raises the risk of later stroke and heart attack, among other health problems.

The estimated prevalence of hypertension among U.S. adolescents is about 3.5 percent. Among the teens from assisted conceptions in the study, it was 15 percent. “This is a small study, and this is not terrible blood pressure, but it’s blood pressure that should alert somebody that we need to be checking it routinely,” says Larry Weinrauch, a cardiologist at Harvard Medical School who wrote an editorial accompanying the article.

As of 2014, more than 8 million babies worldwide had been born as a result of assisted pregnancies, according to preliminary data released in July by the International Committee Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies in Palo Alto, Calif.

The new work follows a 2012 study by the researchers, looking at the same kids as preteens. At that time, Urs Scherrer, a specialist in internal medicine at the University of Bern in Switzerland, and colleagues found that the kids from assisted conceptions had blood vessels with qualities normally found in older adults. The vessels were stiffer and some had thicker walls, features that contribute to a higher future risk of cardiovascular disease.

The blood vessel abnormalities and the higher risk for hypertension may be the result of changes involving chemical tags, called epigenetic marks (SN: 12/24/16, p. 12). These tags are added to DNA or to proteins called histones, and can ramp gene activity up or down. Environmental conditions — such as chemical exposures, diet and stress — can alter epigenetic marks and, therefore, alter the regulation of genes.

Assisted reproductive technologies place mature eggs, or oocytes, and embryos in various environmental conditions that differ from that found in the womb. With in vitro fertilization, for example, mature eggs collected from the ovaries are fertilized with sperm in a lab before being implanted into the uterus. In studies in mice, Scherrer and his colleagues have shown that in vitro fertilization can alter an epigenetic mark that changes the regulation of a gene which is active in the aorta, the main artery of the body. Those mice also developed impaired blood vessels and hypertension.

In humans, “somewhere between the harvesting of the oocytes and the implantation of the embryo in the uterus of the mother is a critical period where epigenetic changes take place,” says Scherrer, who is also a coauthor of the new study.

More work is needed to uncover which epigenetic changes alter the development of the cardiovascular system. That information could perhaps improve assisted reproductive technologies and procedures, for example, by suggesting which environmental conditions outside the womb should be avoided because they may impact the chemical tags.

In the meantime, Scherrer says, doctors should identify people conceived with assisted reproductive technology and monitor them. “Every general practitioner should ask about your fetal and neonatal history,” Scherrer says. The use of these reproductive techniques “will have important effects on your future disease risk.”

The very first child born from IVF, Louise Brown, turned 40 in July (SN Online: 7/25/18). Because kids conceived by these methods are still relatively young, it’s not yet clear if there are other related health effects. Weinrauch says researchers should collect data on the health of kids conceived with assisted reproductive technologies. “We have to start by making people aware of this and finding out if there is anything else going on.”