A telescope dropped dark matter data from the edge of space. Here’s why

This is the story of dark matter, a balloon telescope, chicken roasting bags and a cougar

A NASA super pressure balloon inflates with helium at the Wānaka airport in New Zealand. The balloon carried a telescope for detecting dark matter around the world almost six times in 40 days.

Bill Rodman, NASA

Doomsday came on May 25 for the payload of a pumpkin-shaped balloon at the edge of space.

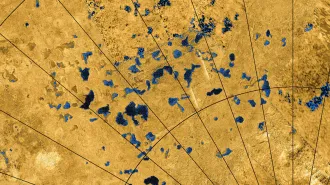

The floating gourd — inflated with more than 500,000 cubic meters of helium and large enough to fit 60 Goodyear blimps inside it — traversed the southern hemisphere some five times in 40 days, toting a telescope that could see the unseeable. NASA’s Super Pressure Balloon-borne Imaging Telescope, or SuperBIT, was on a mission to probe the cosmos for dark matter, the invisible substance thought to scaffold the universe and bind galaxy clusters together (SN: 8/8/22, SN: 6/23/23). By observing how cosmic structures with strong gravity deflect nearby light, SuperBIT could infer dark matter’s presence.

But things had not gone as planned. Early in the mission, satellite communications failed and the telescope’s operators could not retrieve data wirelessly. As SuperBIT made a sixth pass over South America, projections showed the solar-powered telescope heading toward gloomy weather and away from another stretch of land to safely alight upon.

Operators decided to terminate the flight early and anticipated a rough landing, so astrophysicist Ellen Sirks and colleagues instructed the aloft apparatus to send its data to Earth via capsules. The team simulated weather conditions to predict where the escape pods would land.

“We sort of envisioned these [drop capsules] as a redundant way of backing up the data,” says Sirks, of the University of Sydney in Australia. But they became important, she says, “because all the worst-case scenarios came true.”

By the end of the day, SuperBIT had been destroyed; the telescope’s parachute failed to detach upon landing and dragged the craft to pieces. But at 12:31 p.m. UTC, two small packages containing precious dark matter data separated from SuperBIT. Each 1.28-kilogram capsule contained a battery-powered circuit board that stored the data, encased in a foam-wrapped plastic shell sealed in a waterproof chicken roasting bag. They were also equipped with parachutes — bright orange to aid recovery. The team described the new drop capsule system November 15 in Aerospace.

While descending into a rural area in Argentina, the capsules drifted horizontally about 60 kilometers. A search-and-rescue team, following transmissions from the capsules, found the first one 3.8 km from its predicted landing site. The second capsule was found nearly 2 km away and a few meters from its signaled location.

A cougar may have moved the capsule, as a set of tracks was found nearby. Thankfully, the cat was nowhere to be found and had left the capsule unscathed. “We surmise that foam and parachute nylon are intriguing but not tasty,” Sirks and colleagues wrote in the study.

Researchers recovered data from both capsules and, eventually, the telescope’s remains. Sirks and colleagues are still analyzing those data, which she hopes will help map the distribution of dark matter in the universe.

The crash-landing underscores the need for contingency plans, Sirks says, especially since NASA plans to execute many more balloon-borne missions. Her team is working on insulating the batteries in the capsules, which could enable them to transmit their locations as they descend through the cold atmosphere. Eventually, the researchers plan to make the capsule system available for future balloon missions. “It’s a fairly easy, lightweight solution,” Sirks says. “So why not?”