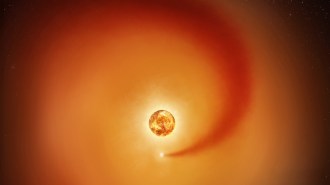

The globular star cluster M92, shown here in an image from the Hubble Space Telescope, appears to be about 13.8 billion years old — the same age as the universe.

ESA/Hubble, NASA, Gilles Chapdelaine

One of the oldest known objects in the universe is wandering around the Milky Way.

Star cluster M92, a densely packed ball of stars roughly 27,000 light-years from Earth, is about 13.8 billion years old, researchers report in a paper submitted June 3 to arXiv.org. The newly refined age estimate makes this clump of stars nearly the same age as the universe.

Refining the ages of clusters like M92 can help put limits on the age of the universe itself. It can also help solve cosmic conundrums about how the universe evolved.

The age is “on the edge of the age of the universe, as estimated by other groups,” says astronomer Martin Ying of Dartmouth College. “It helps us set the lower bound of the age of the universe. We don’t expect M92 to be born before the universe, right?”

Globular clusters like M92 are tight knots of stars that are thought to have all formed at the same time. That makes it easier for astronomers to measure the stars’ ages (SN: 7/23/21). Stars that are born at different masses have different fates: The big ones use up their fuel quickly and die young, and the small ones linger. Figuring out how many of the cluster’s stars have aged out of the main parts of their fuel-burning years gives a sense of when the whole cluster was born.

But those estimates rely on assumptions about how stellar evolution works. Ying and colleagues wanted to find an age measurement that would sidestep those assumptions.

Using a computer, the team created 20,000 synthetic stellar populations for M92, each for a different possible cluster age. They then compared the colors and brightnesses for each of these populations with Hubble Space Telescope observations of M92 and calculated the age that fit the collection best.

This isn’t the first time astronomers have measured M92’s age, but previous estimates relied on just one synthetic collection of stars. Comparing thousands of them reduced the uncertainty introduced by the assumptions baked into each one. The new technique reduced the uncertainty of the cluster age by about 50 percent, Ying says. The team found the cluster is 13.8 billion years old, give or take 750 million years. That’s strikingly close to the best estimate of the age of the universe: a smidge over 13.8 billion years, plus or minus 24 million years, according to the Planck satellite’s measurement of the first light emitted after the Big Bang (SN: 12/20/13).

The age of clusters like M92 is important partly because of a rising tension over how fast the universe is growing. Astronomers have known since the 1990s that the universe is expanding at an ever-increasing rate, thanks to a mysterious substance dubbed dark energy (SN: 8/25/22). But recent measurements of the rate of that expansion, a figure called the Hubble constant, disagree with each other (SN: 7/30/19).

One way around that tension is to accept a different age for the universe, says cosmologist and study coauthor Mike Boylan-Kolchin of the University of Texas at Austin.

“We often think about it as, Moses came down from Mount Sinai with ‘13.8 billion years’ written on some tablets or something, but it’s not quite like that,” he says. “If one takes the Hubble tension seriously, then one also has to say we don’t know the age of the universe that well.”

That’s where M92 comes in. Before spacecraft measured the cosmos’ earliest light, globular cluster ages were the best way to place limits on the age of the universe. That practice had fallen out of fashion for a while, says cosmologist Wendy Freedman of the University of Chicago, who was not involved in the new work.

But improvements in computing, theory, and measurements of the distances to clusters like M92 make it worth trying again.

“The Hubble tension itself is a really challenging nut to crack,” Freedman says. This measurement alone isn’t precise enough to settle the debate. But “the more kinds of constraints we have, the better,” she says. “It’s showing a way for the future.”