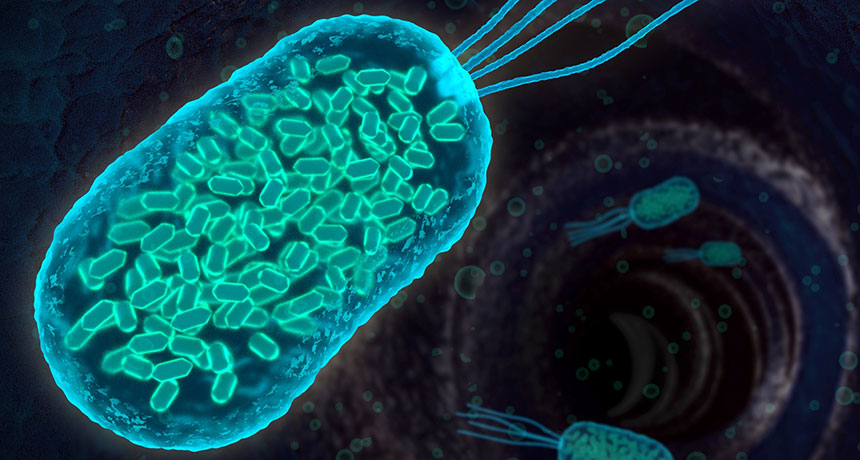

TAGGING BACTERIA Microbes genetically modified to contain gas-filled protein pouches (illustrated) scatter sound waves, generating ultrasound signals that reveal the microbes’ location within the body.

Barth van Rossum for Caltech

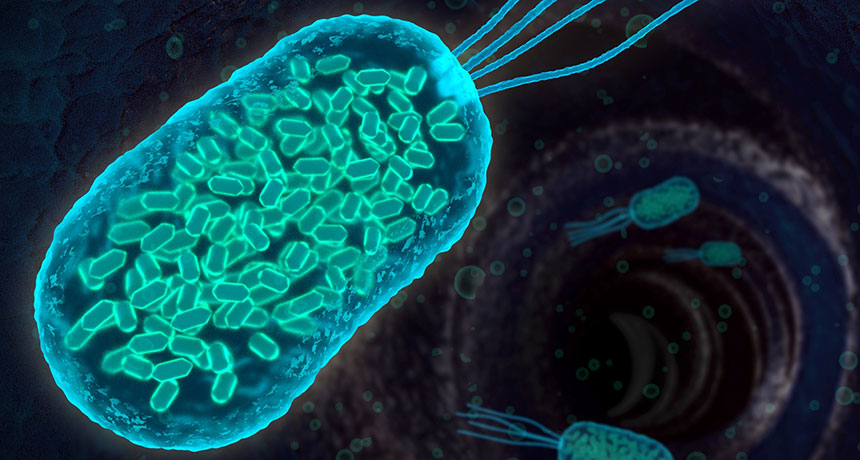

TAGGING BACTERIA Microbes genetically modified to contain gas-filled protein pouches (illustrated) scatter sound waves, generating ultrasound signals that reveal the microbes’ location within the body.

Barth van Rossum for Caltech