A shortage of big sharks along the U.S. East Coast is letting their prey flourish, and that prey is going hog wild, demolishing bay scallop populations.

That’s the conclusion of researchers led by the late Ransom Myers of Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, who died this week. Combining census surveys from the past 35 years, Myers’ team found shrinking populations of big sharks and shellfish and increasing numbers of smaller sharks and rays.

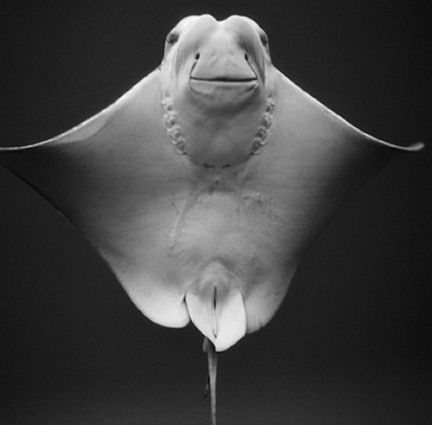

“Affecting something at the top [of the food web] is going to have huge consequences as effects ramify through the system,” says study collaborator Charles H. Peterson of the University of North Carolina’s Institute of Marine Sciences at Morehead City. As part of the new study, he and his colleagues explored some of those effects by protecting bay scallops from the cownose ray (Rhinoptera bonasus), one of the flourishing midlevel predators.

Fisheries worldwide are destroying large sharks, both intentionally and accidentally (see New Estimates of the Shark-Fin Trade). Several research surveys plus fisheries data show that the 11 shark species that eat smaller sharks, rays, and skates along the East Coast have all declined since 1972, say the researchers.

Sharks that are 2 meters or more in length are virtually the only predators tough enough to hunt significant numbers of the region’s smaller sharks, rays, and skates, says Peterson. In surveys of 14 of these prey species, 12 have increased in number during the past 3 decades, some showing a 10-fold boost.

Peterson embarked on his field studies after hearing North Carolina fishermen complain that a surge in cownose rays was depleting the already-beleaguered bay scallops.

To test the influence of rays on scallop populations, Peterson and his colleagues encircled patches of scallops with stockades of widely spaced poles. The rays typically don’t turn sideways to thread between the poles, although most other creatures swim through them easily.

After the fall migration of rays in 2002 and 2003, formerly dense bay scallop populations virtually disappeared from patches without stockades. However, roughly half the scallops inside the stockades remained. Peterson says that count may underestimate survival among the protected group since scallops easily swim out of the enclosures.

A survey in the same locations in the early 1980s found that ray migrations didn’t deplete scallop populations, Peterson notes.

The new findings, which are reported in the March 30 Science, could affect efforts to replenish beds of shellfish such as oysters. Without excluding predators, says Peterson, “you have a ray-feeding station.”

The link between shark and shellfish declines is reminiscent of patterns in Pacific ecosystems, says ecologist James Estes of the University of California, Santa Cruz. In 1998, he and his colleagues found that when killer whales off Alaska increased their consumption of otters, sea urchins thrived and ravaged kelp forests (SN: 10/17/98, p. 245).

Marine ecology traditionally didn’t focus on top-down effects, but Estes sees growing evidence of their importance. “That’s almost a paradigm shift,” he says.