When brain’s GPS goes awry, barriers can reboot it

Running into a literal boundary aids reorientation, mouse study shows

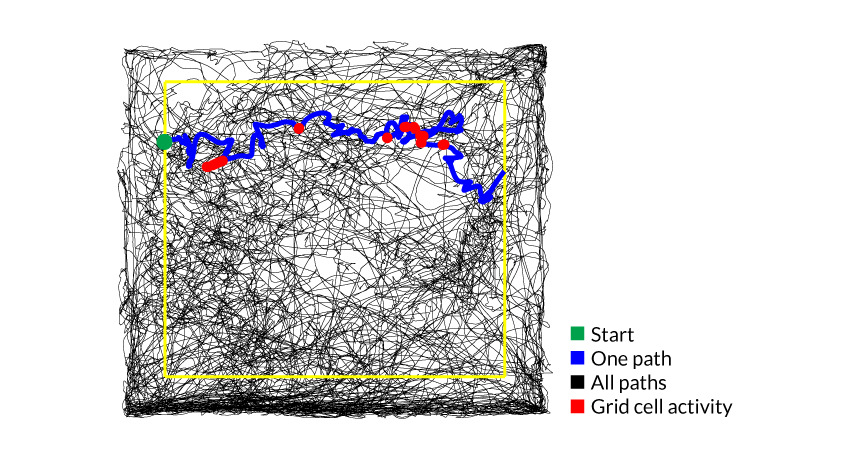

MOUSE MAP As a mouse meanders farther away from a border (one path highlighted in blue), a grid cell’s pattern of behavior (red) becomes less regular, distorting the animal’s internal map. Hitting the border can reset it, a study suggests.

Hardcastle et al/Neuron, 2015