Chocolate Therapies (with Recipe for Janet’s Chocolate Medicinal Mousse Pie)

Chocolate has made news over the past few months for the apparently heart-healthy properties of some of its components–antioxidants known as flavonoids (see Chocolate Hearts: Chocolate Hearts.) These findings, together with data reported several years ago on the treats’ ability to turn on opiate receptors in the brain (SN: 10/12/96, p. 235), threaten to transform the image of chocolate from dietary vice to herbal medicine.

To meso-American anthropologists, however, the idea that chocolate can be health-promoting is old hat–very old hat.

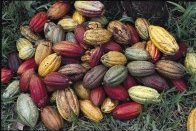

Revered by cultures throughout the Americas for some 3000 years, chocolate has been in cultivation since at least the time of Christ. Referred to for much of that time as a “food of the gods,” this botanical product has occasionally, in centuries past, even stood in for currency–its value on par with gold’s. For much of this illustrious past, chocolate has also been a venerated staple of the herbal pharmacopoeia, observes Louis E. Grivetti of the University of California, Davis.

At the American Association for the Advancement of Science meeting last month in Washington D.C., Grivetti shared findings from his new historical investigation of chocolate’s medicinal history. His team turned up medical texts describing chocolate therapies dating back to 1522. Though written by Europeans, they described remedies brought back by explorers who had visited the New World. So compelling were their reports that soon Europe was importing huge quantities of cocoa beans to serve a growing market for therapeutic chocolate.

The earliest texts suggested that cocoa was merely a vehicle for helping make less palatable medicines go down. Soon, however, it was regarded as an active ingredient in cures being offered for a broad range of ails.

Healers pounded cocoa beans into a paste. Diluted into a drink, they gave it to people suffering from fevers, liver disease, and kidney disorders. Physicians prescribed ground beans, mixed with resin, to cure dysentary. A cocoa drink was reputed to foster needed weight gain–especially if augmented with ground maize. Hot chocolate was even prescribed as a laxative and aid to digestion.

By the early 1600s, European researchers were reporting indications that chocolate may affect moods. Grivetti found a 1631 treatise by the Spanish physician/surgeon Antoino Comenero de Ledesma, for instance, that said chocolate makes people amiable, and “incited consumers to . . . lovemaking.”

Indeed, Grivetti says, because chocolate was perceived as an intoxicant, it was deemed unsuitable for women or children–at least until the 14th century.

By Ledesma’s time, however, healers realized that chocolate was not for men only. A love potion, drinking chocolate helped women conceive, he reported. If hot cocoa was drunk during pregnancy, it helped smooth labor and delivery.

Three decades later, Henry Stubb published a monograph that claimed a drink made by mixing chocolate and vanilla would strengthen the brain and womb. Mixed with Jamaican pepper, chocolate was supposed to stimulate menstrual flow. Combined with resin, it was reputed to boost breast-milk production. Cocoa-bean oils even helped heal a nursing mother’s cracked nipples.

Few conditions aren’t improved by chocolate, according to the texts that Grivetti’s team of scholars uncovered and translated. The botanical product was used to treat tuberculosis, toothaches, and ulcers. It was alleged to cure itches, repel tumors, and foster sleep. By the 1680s, reports emerged that chocolate could restore energy after a day of hard labor, alleviate lung inflammation, or strengthen the heart. By the 1800s, cocoa was being mixed with ground amber dust to relieve hangovers. Combined with other ingredients, it became the basis of treatments for syphilis, hemmorhoids, and intestinal parasites.

In traditional healing recipes, chocolate often included little or no sweetening. Moreover, the Native American view of medicine in which chocolate therapies evolved was somewhat different from that practiced in Europe. Rather than illness being caused by disease, Native Americans viewed health as the state of being in balance with the environment. Losing that balance–perhaps through a perturbed diet–could create sickness. Chocolate was viewed as one means for restoring lost balance.

European adventurers often sampled the native cocoa-based drinks with scorn, according to Historicus in his late-19th century book, Cocoa: All About It. These beverages, frequently laced with cinnamon, chili peppers, oregano, or cloves, struck the European palate as vile.

Travelers nonetheless brought home recipes for the strange drinks, together with tales of their reputed therapeutic prowess. Sugar crept into the recipes, and almost at once, Europeans developed a huge appetite for chocolate. Today, some of the most prized chocolates emerge from European candy factories.

In the United States, per capita chocolate consumption already exceeds 12 pounds per year. Europeans tend to eat even more. Though physicians no longer prescribe chocolate as aids to digestion, lung ailments, or ulcers, research suggests that self-medicating ourselves with at least some of these products–especially those made from dark chocolate–may achieve real benefits, especially in maintaining cardiovascular health.

While this should not be interpreted as reason to overindulge in these fat-rich confections, Norman K. Hollenberg of the Harvard Medical School in Boston believes the growing body of nutritional studies of chocolate are strong enough to argue, “People should not feel guilty about eating it.”

Janet’s Chocolate Medicinal Mousse Pie

Serves 8 to 12

This recipe, a household favorite, wows guests who–even after finishing a sinfully rich slice of pie–never suspect that the main ingredient is tofu. In the past, I’ve always billed the dessert as heart-healthy, based on studies suggesting that soy products can offer cardiovascular and anti-cancer benefits. In fact, I adapted this recipe from a fattier and more heavily sweetened version that was served 6 years ago to me and other attendees of the First International Symposium on the Role of Soy in Preventing and Treating Chronic Disease.

Despite the pie’s soy base, however, I often felt a twinge of guilt over the heavy dose of chocolate present in each slice.

With the newly emerging data on dark chocolate’s flavonoids, I now feel less self-conscious about serving this popular dessert. I can point out that its bounty of chocolate may actually contribute to the pie’s offering of a cardiovascular double whammy. And the stearic acid in chocolate, although a saturated fat, is the type that doesn’t appear to raise serum cholesterol.

Want a triple whammy? Serve with a cup of strong, flavonoid-rich darjeeling tea. The especially good news: This pie is so rich that it’s easy to be satisfied with a very small slice.

- 2 boxes of low-fat Mori-Nu silken tofu (12.3-ounces each, any firmness)

- 1 10-ounce package of semi-sweet chocolate chips

- 1/3 tsp. sugar

- 1/3 tsp. water

- chocolate-cookie no-bake pie shell

- raspberries or strawberries (garnish)

Melt the chocolate in the top of a double boiler until the chips retain their shape but are soft as warm butter. Remove from heat and let stand a couple minutes.

Puree the tofu in a food processor–about 2 minutes–frequently scraping down the sides of the mixing bowl to ensure that all of the tofu is converted from a soft brick into a warm-pudding consistency. Add the water to the sugar, then mix both into the tofu. Add the softened chocolate and stir until thoroughly mixed. Pour into a chocolate-cookie pie shell and swirl the top to make soft peaks, like frosting a cake. Garnish with berries. Then chill to set. Ready in 1 hour.