A new diabetes treatment could free people from insulin injections

In a small trial, 10 of 12 type 1 diabetes patients no longer needed supplemental insulin

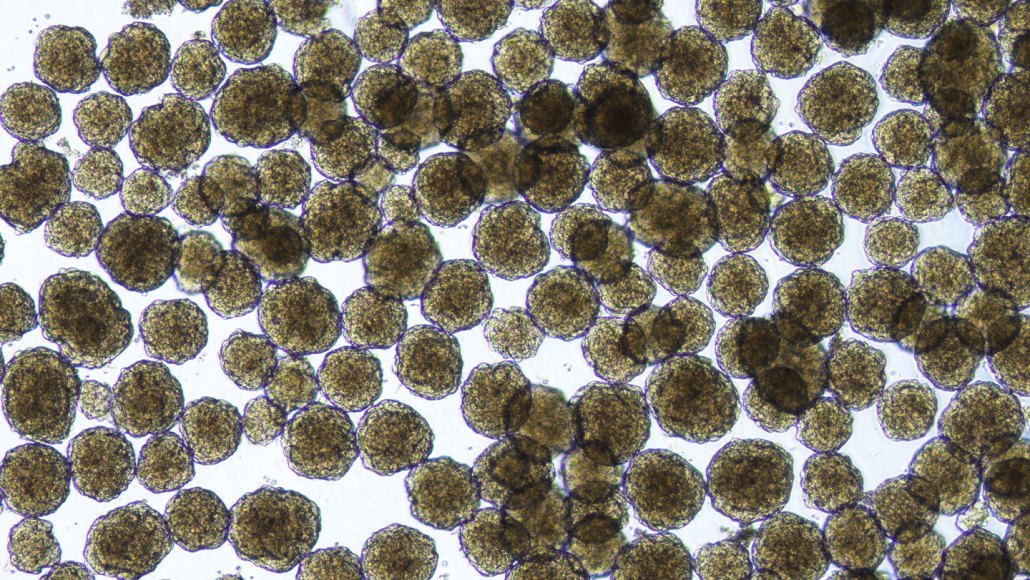

These human islet cells, which were created in the lab using stem cells, are part of a new therapy for people with type 1 diabetes.

Vertex Pharmaceuticals