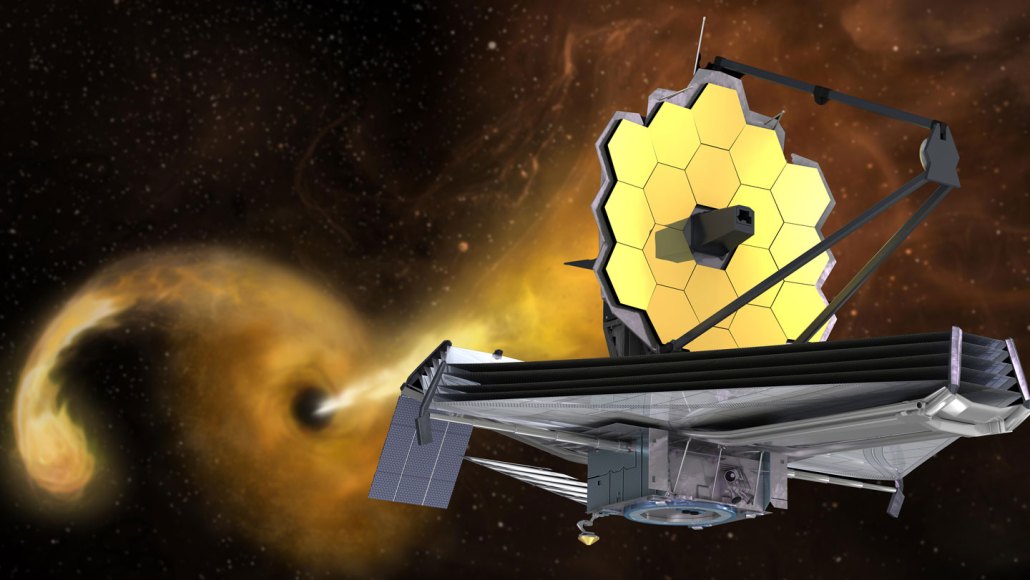

The James Webb Space Telescope took its first look at black holes shredding and feasting on stars (illustration shown).

NRAO/AUI/NSF, NASA

The James Webb Space Telescope took its first look at black holes shredding and feasting on stars (illustration shown).

NRAO/AUI/NSF, NASA