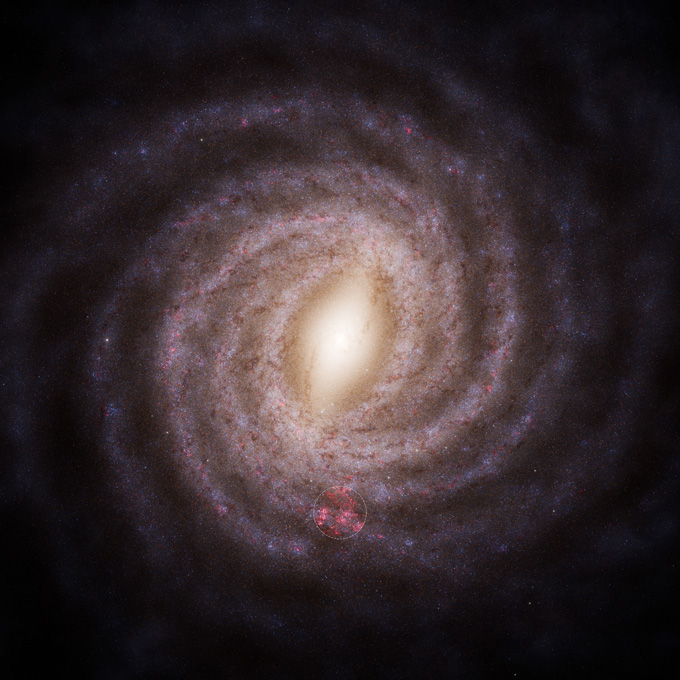

See a 3-D map of stellar nurseries based on data from the Gaia telescope

The nurseries are charted within about 4,000 light-years from the sun in all directions

A new 3-D map shows all the star-forming clouds (shown in red) within about 4,000 light-years from the sun in all directions.

ESA