Life-saving research on extreme heat comes under fire

“We know heat is the number one weather-related killer across the United States.”

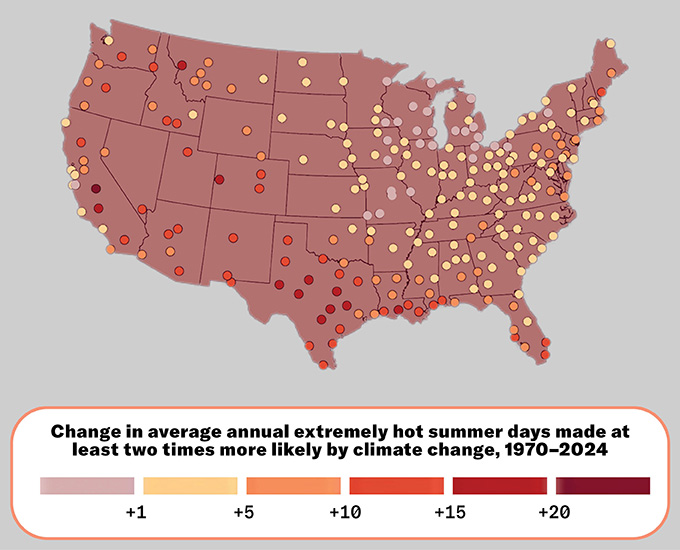

Cuts to federal funding for heat research are happening even as extreme heat waves are becoming more common.

Martin O’Neill

This is a human-written story voiced by AI. Got feedback? Take our survey . (See our AI policy here .)

Located just a few hours’ drive from the Canadian border, Missoula, Mont. is not known for sweltering temperatures. And yet heat waves are becoming more common in the mountainous region due to climate change, and researchers are concerned that a catastrophic heat event could soon shock the 120,000 or so people who call Missoula County home. Recent history reveals the cost of being unprepared for extreme heat; in 2021, the Pacific Northwest was caught off guard by the strongest heat wave the region had seen in a thousand years, resulting in more than 1,400 deaths.

“We’ve come to understand that heat is a major threat to our region,” says Alli Kane, the Climate Action Program Coordinator for Missoula County. “And it’s something that we’re not prepared for.”

In January, Missoula successfully applied to work with the Center for Collaborative Heat Monitoring, a federally funded partnership of science museums and heat experts tasked with mapping heat in communities across the country. The virtually based center had planned to provide expertise and $10,000 in funding to Kane and her colleagues to identify the hottest places across Missoula County.

But in May, federal funding for the Center for Collaborative Heat Monitoring was terminated.

The boots-on-the-ground effort would have provided a more detailed picture than satellite data of where Missoula’s heat was most intense, helping the county focus its efforts where they were most needed. “This is life-saving data,” Kane says. “We know heat is the number one weather-related killer across the United States.” In the last decade, heat has on average killed more people each year than floods, tornadoes and hurricanes combined.

The center is one of many casualties in the Trump administration’s cuts to research into extreme heat nationwide. Many of those cuts were part of the administration’s attack on climate science and environmental justice. But the impacts to heat research have been especially rough, because many unanswered questions remain about how heat affects different populations, how to manage heat and how to keep people safe.

“Every heat-related death is potentially preventable,” says Kristie Ebi, an epidemiologist at the University of Washington in Seattle who studies the human health impacts of climate warming. But with all the unanswered questions, “they’re not being prevented.”

The cuts come at a time when extreme heat waves are becoming more common and intense as the climate warms from humankind’s burning of fossil fuels. The 10 most recent years have been the 10 warmest ever recorded. Last year was the hottest so far. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate more than 700 people die from heat annually in the United States. But heat-related deaths are drastically underreported; the true toll may reach up to 15,000 fatalities each year, says environmental epidemiologist Tarik Benmarhnia of the University of California San Diego.

The Center for Collaborative Heat Monitoring was created in 2024 by the National Integrated Heat Health Information System, or NIHHIS. It’s a partnership of federal agencies established during the Obama administration to generate and share science-based information and tools to keep people safe from heat. Since 2015, NIHHIS has supported heat mapping campaigns in urban and rural areas, helped produce resources like the Heat.gov website and the HeatRisk online tool, and funded a swath of efforts to make communities more resilient against extreme heat.

But this year, NIHHIS has been devastated by funding cuts to programs and by people being fired or choosing to leave, says Juli Trtanj. She left her role as executive director of NIHHIS in April, partly because so many of her colleagues departed. “The ability for forward planning, the long-term stuff, any of that, is just gone,” she says. Due to the government shutdown in October, NIHHIS officials did not respond to requests for comment.

The Center for Collaborative Heat Monitoring was supposed to map roughly 30 communities over the next three years. The first cohort of 11 communities had already been selected. That included Missoula County, which had been in the middle of planning when the news landed. The terminated funds would have gone to organize and support the volunteers who would be mapping heat throughout the county. Instead, “there was a lot of unknown, a lot of confusion,” Kane says.

In 2024, NIHHIS also created the Center for Heat Resilient Communities in Los Angeles. That center was meant to use science to tailor blueprints for managing heat in communities across the country, while giving researchers an opportunity to test heat planning strategies in a mix of settings. But like the Center for Collaborative Heat Monitoring, its funding was terminated.

Layoffs also have slammed the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, or NIOSH, the only federal research entity that studies how heat harms workers. Around 90 percent of its workers were laid off in spring. While a fraction has since been reinstated, NIOSH heat experts are among those who have not returned. The first federal standard protecting workers from heat, which was based on NIOSH guidance, was proposed in 2024. But laid-off NIOSH heat experts were unable to defend the standard in public hearings this summer, fueling concerns about its fate.

Additional cuts to funding from the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health and other federal sources have further weakened the heat research ecosystem.

Benmarhnia, of UC San Diego, studies how extreme heat and other climate risks affect public health. From January to June, he was forced to scrap research plans, including a project on heat’s impacts on unhoused people, and to shrink his team of more than 30 researchers to fewer than 10. “That was horrible,” he says. Researchers are now forced to avoid using keywords like “climate” and “environmental justice” in grant applications, Benmarhnia says. But it’s nearly impossible to divorce heat from those concepts.

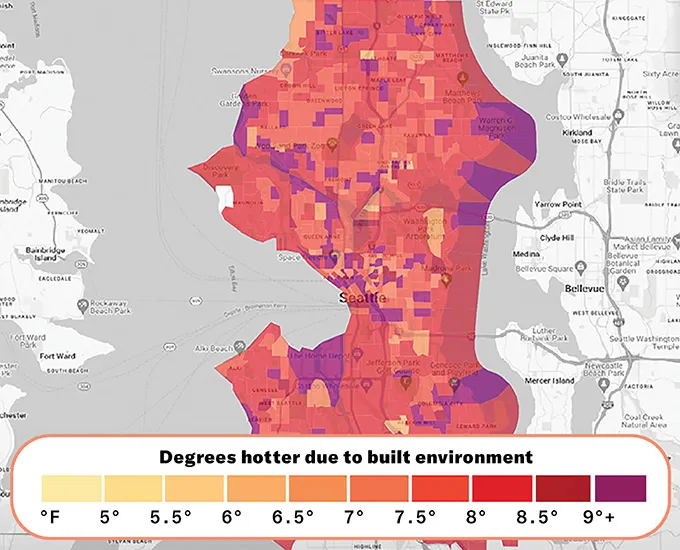

For instance, a 2020 study of nearly 500 U.S. urban areas found that poorer and nonwhite urban residents tended to experience more intense summer daytime heat. The United States had an opportunity to build heat management programs that place equity at the fore from the ground up, says Kelly Turner, an urban environment researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Center for Heat Resilient Communities. But “that opportunity has been squashed.”

Benmarhnia worries the cuts will not only impact the direction of heat research, but also could lead to fewer scientists studying heat in general. His concerns resonate with Mayra Cruz, a University of Miami heat and health researcher who expects to finish her Ph.D. soon. While Cruz doesn’t see a scarcity of jobs working on flooding and other environmental hazards, “I don’t see any heat positions,” she says. “That definitely signals to me that there’s a difference there in how we’re thinking about heat in this administration versus other issues.”

And if heat researchers move overseas to pursue funding, that could lead to more U.S. lives lost over time, Trtanj says. Roughly 75 percent of the 1,608 scientists who responded to a Nature poll said they were considering leaving the country following disruptions to science by the Trump administration. “The knowledge that we should be learning about what works for the U.S. economy and U.S. citizens, that’s being applied to other countries,” she says.

Even with the losses in funding and personnel, folks have found ways to keep some heat research alive.

In Missoula County, a fleet of more than 30 volunteers drove a dozen routes through both rural and urban areas on August 12, gathering data on heat and humidity with antenna-shaped sensors mounted on their vehicles.

The work was made possible because Kane and her colleagues managed to piece together a small amount of funds to replace some of the lost federal dollars. They used it to pay for technical guidance, equipment and data analysis by the Center for Collaborative Heat Monitoring and CAPA Strategies, a Portland, Oregon–based consultancy that supported the heat-mapping efforts in Missoula and most of the other communities. But gaps remain.

“We had, with Missoula, also intended to do some longer-term monitoring and modeling [and] other community engagement,” says Max Cawley, the center’s director who is based in Raleigh, N.C. “Those became incredibly challenging to try to figure out how to fit into a very busy and now unfunded set of summer projects.”

Smaller entities such as states, local governments and community-based organizations are trying to fill the gap, but many communities lack the resources and expertise to address extreme heat on their own.

“Climate impacts are already hurting vulnerable communities the most,” says Susan Teitelman, a climate resilience specialist at Climate Smart Missoula, a local nonprofit that helped organize Missoula’s heat mapping effort. “When federal funding is taken away, those groups or communities are going to be harmed first and hardest,” she says.

For now, it falls upon senior scientists to keep the candle burning, Benmarhnia says. “That’s really how I see my responsibility right now,” he says. “To keep doing it.”