As wildfires worsen, science can help communities avoid destruction

Roughly 3.5 billion people live where some of the most destructive fires have occurred

The Eaton fire killed 19 people and destroyed more than 9,000 buildings in January. It was one of the 14 wildfires that ravaged Southern California that month.

Josh Edelson/AFP/Getty Images

Bright flecks of burning wood stream through the smoky air and toward a hapless house. Before the one-story structure, the glowing specks, each merely centimeters in size, seem insignificant. But each lofted ember is a seed of destruction. Researchers estimate that embers cause somewhere between 60 to 90 percent of home ignitions.

Next to the house stands a trash bin, its lid propped open with sheets of cardboard inside. The fiery spores enter and in seconds flames sprout inside. Within minutes, a column of fire rises and licks the house’s sidewall. Black flaps of vinyl siding begin to peel and writhe. Burning chunks fall to the ground, and a crackling, smoldering fissure grows up the wall. Orange, blue and purple flames roar as they ascend toward the roof.

Then, a hiss pierces the air as firefighters step forward to spray the flames. Their intervention is not serendipitous. The burning home is not a real home. It is just the side of one, as if a giant butcher had trimmed a neat piece of a house’s exterior. The conflagration had been staged in a vast room at the National Fire Research Laboratory in Gaithersburg, Md.

Blazing bins

A melted splotch is all that remains of a trash bin after a wildfire in Los Angeles in January (top). At the National Fire Research Laboratory in Gaithersburg, Md. (bottom), scientists tested how trash bins fuel the spread of fires.

Standing before the ruined structure, Alexander Maranghides, a fire protection engineer at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Gaithersburg, Md., assesses the damage. “All from embers,” he says.

Experiments like this one reveal key details about how wildfires devastate individual structures and entire communities, as they did around Los Angeles earlier this year and in Maui in 2023. The information is crucial for protecting the communities that are most vulnerable to encroaching wildfires — those within the wildland-urban interface, or WUI. That’s land manager jargon for anywhere that human development meets or mingles with undeveloped natural areas, such as forests or grasslands. Roughly 40 percent of people on Earth — some 3.5 billion — live along these fringes of nature, where most of the deadliest and most destructive fires in recent history have occurred.

As these fire-prone zones globally expand, climate change is making fire seasons longer, hotter and drier. When those conditions converge with powerful winds that can fan flames and carry embers for kilometers, communities can be overwhelmed.

“Wildfire control doesn’t work during the extreme conditions,” says Jack Cohen, a retired U.S. Forest Service fire scientist who spent decades studying fire in the wildland-urban interface. The focus needs to shift away from fighting blazes and toward modifying communities to resist catching fire, he says. “It’s not a wildfire problem. It’s a structure ignition problem.”

For decades, Maranghides and other researchers have dedicated themselves to figuring out how to make communities more resilient, resulting in guidelines like NIST’s Hazard Mitigation Methodology, first released in 2022. It identifies dozens of vulnerabilities and how to lessen them. It also raises a key point: In neighborhoods where homes are closely spaced, fire resilience works only if the whole community is involved.

That’s because a home on fire can spread flames to other structures that are within about 50 feet. In such neighborhoods, hardening only some of the structures leaves them all vulnerable, Maranghides says. Once a home ignites in flames, it transforms into an existential threat to its neighbors. Even a single unprotected building can jeopardize the whole neighborhood. Hardening all the buildings in a community is the only way to protect each of them.

That’s the crux of the problem: getting each resident involved in hardening the community. Guided by the principles from NIST and similar methodologies, community-scale hardening has started in some places in the West, reflecting a recognition that society must adjust to coexist with fire, so long as people live within its reach. “Wildfire is inevitable,” Cohen says, “but community destruction doesn’t have to be.”

Lessons from devastation

On November 17, 2018, a team of NIST researchers traveled to the foothills of California’s Sierra Nevada to investigate the most destructive fire the state had ever seen. About a week and a half earlier, katabatic winds ripping down from the mountains had snapped a power line, igniting flames in a steep-sloped waterway called Feather River Canyon around dawn.

By sunset, the fire had ripped through the towns of Concow, Paradise and Magalia, destroying more than 18,000 structures, damaging 7,000 and killing 85 people. Much of the Camp Fire’s spread occurred via the sky. The wind lofted embers for kilometers, seeding new blazes far ahead of the main fire front. “It’s a kind of a hopscotch,” explains Steve Hawks, a wildfire researcher and veteran firefighter who spent 30 years working for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, or CAL FIRE. “Eventually [the] main fire front will catch up to it, but it’s trailing behind.”

The NIST team had arrived while the flames were still burning. They spent four days in the field, documenting damage and speaking with meteorologists and first responders on site. Nearly a dozen deployments followed over the next six months. Data was gathered from a multitude of sources, from fire engine logs to evacuation information. NIST has since spent over six years analyzing that data. Its first report on the Camp Fire was released in 2023, and another is slated for 2026.

Because these reports are so comprehensive, NIST’s WUI Fire Group has completed just four fire case studies. “Think of it as CSI at the community level,” Maranghides says. Field observations help guide NIST’s fire research in the lab. For instance, researchers noticed that fences were acting as conduits for spreading flames, prompting research into how fence design and materials affect fire spread. And observations of burning sheds spreading flames to residences led to experiments that helped determine that wooden or steel storage sheds should stand at least 4.5 meters away from homes. When a shed catches fire, its walls seal in heat and flammable gases, which can cause jets of fire to shoot out of any openings. “The shed simulates wind,” Maranghides says.

NIST researchers also design experiments to study how flames and embers ignite and spread on or between structures made of different materials, in various circumstances. These tests reveal the conditions under which a vulnerability becomes dangerous, Maranghides says. That information then goes into updates to NIST’s blueprint for fire-adapted communities — the Hazard Mitigation Methodology, or HMM.

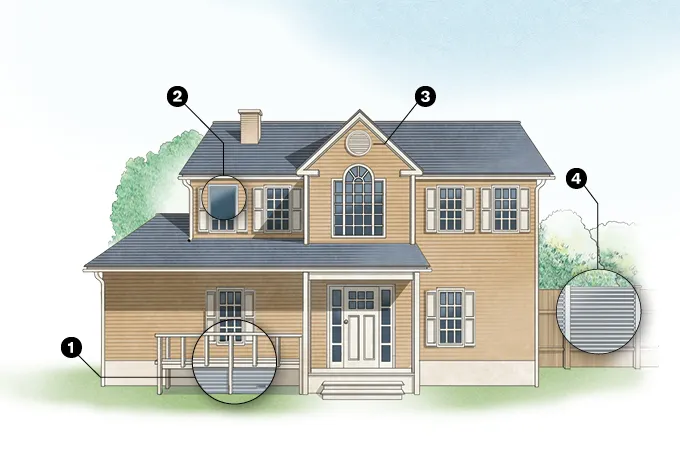

Embers are not welcome

- Add noncombustible skirting around the deck to prevent ignition underneath.

- Dual-paned tempered glass windows with noncombustible frames are less likely to break or burn. A metal window screen provides additional protection.

- Install fine metal mesh with ⅛ inch openings behind vent covers to help keep embers out of the attic.

- Use metal or other noncombustible fencing within 2.5 meters (8 feet) of the house.

NIST’s methodology combines approaches to prevent a community from burning down when faced with a fire. The first involves hardening structures against flames using resilient designs and materials. For instance, metal siding could be used to shore up the base of a wall. The second approach entails removing, relocating or reducing a home’s exposure to materials that could ignite from embers and spread flames, such as patio furniture, plants or vehicles.

While the HMM may sound like a typical fire code, it’s more of a “code plus,” Maranghides says. Unlike conventional fire codes, the methodology emphasizes community-scale efforts rather than addressing just one home or property, Maranghides says. Fire doesn’t care about property lines.

“Your parcel could be pristine, so that you could have done everything right, but those neighboring parcels all around you have to also be prepared,” agrees Michele Steinberg, wildfire division director of the National Fire Protection Association, a nonprofit based in Quincy, Mass., that helps develop fire safety codes.

And for each home in the community, every vulnerability must be addressed. In places where homes are within 15 meters of one another, embers could ignite one home and trigger a destructive domino effect — flames spreading from structure to structure. “When you get bombarded by a million embers, those embers are going to find those vulnerabilities,” Maranghides says. “You cannot just do half the ember hardening. It doesn’t work that way.”

Other fire protection guidelines miss vulnerabilities identified by NIST, Maranghides says. Roughly 75 percent of the ember vulnerabilities and 50 percent of the flame vulnerabilities in the HMM are lacking from fire building codes from California, the National Fire Protection Association and International Code Council, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit that publishes safety standards, he says. “The code is not enough.”

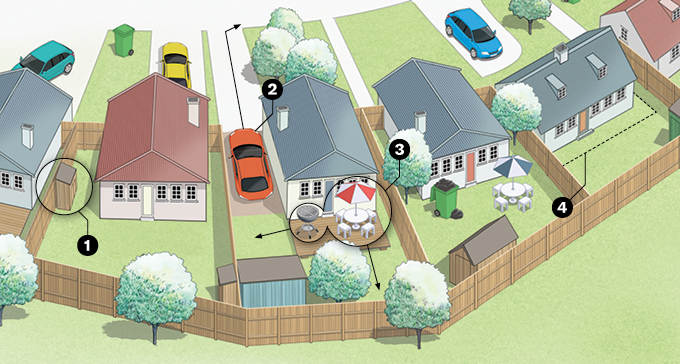

Fending off fire

- Even if a shed is a safe distance from one home, it may pose a threat to the community if placed too close to a neighboring home.

- Move vehicles at least 30 feet away from homes during times of increased fire risk.

- Move combustible items from decks or replace with less hazardous metal outdoor furniture.

- Create a zone of at least 1.5 meters (5 feet) around a house that’s free of items that can catch fire, including wooden furniture, trees and trash bins.

One guidance that’s comparable to NIST’s is the Wildfire Prepared Neighborhood Standard. It was developed by the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety, a research and communications nonprofit organization that’s funded by property insurance companies and based in Richburg, S.C.

The institute conducts fire experiments and field studies of wildland-urban interface fires, producing findings that often align with NIST’s. For instance, while surveying the aftermath of the Palisades Fire, Hawks and colleagues observed plastic trash bins with holes melted through them, suggesting embers could penetrate even closed bins. What’s more, they found the remains of trash bins — melted plastic and metal axles — near burned sections of buildings. “We noted a lot of damage … came from those bins where the ember would land on top,” says Hawks, who is the institute’s senior director for wildfire. The institute recommends that residents move bins at least 30 feet away from homes during long absences and Red Flag warnings, an alert indicating increased fire risk due to warm, dry and windy weather.

Though many of the measures in Wildfire Prepared Neighborhood align with or have been drawn from NIST’s work, the institute goes one step further by certifying homes and communities that meet the standard, Hawks says. The certification may help people secure home insurance at a time when insurance companies in California and other states are dropping thousands of homeowners’ policies due to increasingly severe and costly climate disasters.

Earlier this year, developers unveiled a new community of 64 homes in Escondido, Calif., called Dixon Trail. It is the first community to receive the Wildfire Prepared Neighborhood designation from the insurance institute. Each of the homes is insured, Hawks says, despite California’s tough insurance market.

Someone visiting Dixon Trail might not immediately spot anything unusual about the homes. They may overlook the enclosed eaves that help keep out embers, the dual-paned, tempered glass windows that are resistant to breaking in high heat and the metal fences that won’t catch fire. But what might stand out is the five-foot zone surrounding each house that’s largely free of combustible material — be it mulch, furniture or plants — surrounding each house.

As strong as the science is, “it’s only as good as the implementation,” Steinberg says. The real question, she says, is “how do we get there?”

Bringing science to the neighborhood

The Dixon Trail community may be impressive, but the largest opportunity for protecting communities from wildfire lies in refitting homes that already exist.

Around 130 kilometers north of San Francisco lies Clear Lake, the largest natural body of freshwater located wholly within California and the namesake of Lake County. Two cities, numerous towns and countless oak trees surround the lake’s bass-filled waters. Fire is a recurring part of life here. Just 3 months ago, the Lake Fire burned 401 acres near Clear Lake’s eastern shore.

“Pretty much everyone who lives here or lives in the surrounding area has been traumatized by fire one way or another, whether it’s being evacuated or losing their home,” says Deanna Fernweh, a resident who was born and raised in Lake County. “It feels like a crisis that we can never really run away from.”

On Clear Lake’s southern shore lies Kelseyville Riviera, a relatively new community of about 1,500 homes and 3,400 people. Here, a state-led initiative called the California Wildfire Mitigation Program is partnering with the Federal Emergency Management Agency and local organizations to help people retrofit against fire. Their standards are informed by the HMM, the California building code and CAL FIRE materials tests.

Communities were selected based on their vulnerability to fire and future impacts from climate change, as well as how many residents are older, disabled, living in poverty, without a car and with language barriers.

Lake County is one of six counties selected for the program so far, and Kelseyville Riviera was identified as particularly at risk. “We have dense vegetation that surrounds that community … really only one way in, one way out, and the road is narrow,” says Fernweh, who is program manager for North Coast Opportunities, a nonprofit leading the project. “A lot of the lots are small, so some of these homes are only 25 feet away from each other and, as you know, fire hops from rooftop to rooftop,” she adds. “It just kind of checked all those boxes as being one of the most vulnerable areas in Lake County.”

There are big advantages to partnering with local organizations to retrofit homes. “First, it’s a lot easier to have a neighbor to come and talk to you about this stuff, than have me come from Sacramento,” says J. Lopez, executive director of the California Wildfire Mitigation Program in Sacramento, a state program that provides financial assistance to fire-prone areas. “Second of all … now the knowledge system is in the community.”

The initiative is still in its infancy. So far, at least 30 homes in Kelseyville Riviera have been retrofitted, part of 70 completed across the state so far. Another 200 homes across the state have been assessed or are currently being retrofitted, and hundreds more people have applied. The cheapest retrofit so far, on a Lake County home, cost about $36,000, Lopez says, while the most expensive, at about $110,000, was in San Diego County.

Lopez hopes the effort will scale up once it advances past the pilot phase. In 2028, the California Wildfire Mitigation Program Authority is due to submit a report to the California legislature that details the costs, challenges and objectives of the initiative, with the goal, Lopez says, of making the program permanent.

U.S. Census Bureau data show that new homes built from 2020 through 2022 make up only 2 percent of owner-occupied homes, underscoring the vast need for retrofits. But it’s hard to get people on board, especially if they must foot the bill, Steinberg notes. “It will take everybody working together, and it will take change in policy and practice from the national down to the local level.”

That alignment may take years to achieve. “No single entity — federal, state, local, public or private — actually has full authority over this issue,” says Frank Frievalt, director of the Wildland-Urban Interface Fire Institute at Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo, Calif.

In the meantime, Frievalt refers people to the guidelines provided by NIST and the Insurance Institute. “Don’t wait on your local government, don’t wait on your insurance, don’t wait on a fire inspection,” Frievalt says. “Look at the things that you can do to protect your home. The goal is not insurability. The goal is survivability.”

The good news is that the threat of fires on the wildfire-urban interface are a solvable problem. But “this is not going to turn on a dime,” Maranghides says.

Still, he foresees a scenario a generation from now, when a wild land fire runs up against a community, it will simply peter out.

Compared with earthquakes, twisters and so many other natural hazards, fire may be the natural phenomenon that is most within our control to mitigate. “In a tornado … the energy is in the atmosphere,” Maranghides says. “Here, the energy is in the community.”