A citizen scientist surveys bleached corals around Koh Tao Island in southern Thailand on June 14, 2024. Marine heat waves hit 80 percent of the world’s warm water coral reefs in 2024, causing the worst bleaching and coral die-off on record. It’s the point of no return for coral reefs, researchers say; as global temperatures continue to rise, Earth has officially passed its first climate tipping point.

LILLIAN SUWANRUMPHA/Contributor/Getty Images

Earth has entered a grim new climate reality.

The planet has officially passed its first climate tipping point. Relentlessly rising heat in the oceans has now pushed corals around the world past their limit, causing an unprecedented die-off of global reefs and threatening the livelihoods of nearly a billion people, scientists say in a new report published October 13.

Even under the most optimistic future warming scenario — one in which global warming does not exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial times — all warm-water coral reefs are virtually certain to pass a point of no return. That makes this “one of the most pressing ecological losses humanity confronts,” the researchers say in Global Tipping Points Report 2025.

And the loss of corals is just the tip of the iceberg, so to speak.

“Since 2023, we’ve witnessed over a year of temperatures of more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above the preindustrial average,” said Steve Smith, a geographer at the University of Exeter who researches tipping points and sustainable solutions, at a press event October 7 ahead of publication. “Overshooting the 1.5 degree C limit now looks pretty inevitable and could happen around 2030. This puts the world in a danger zone of escalating risks, of more tipping points being crossed.”

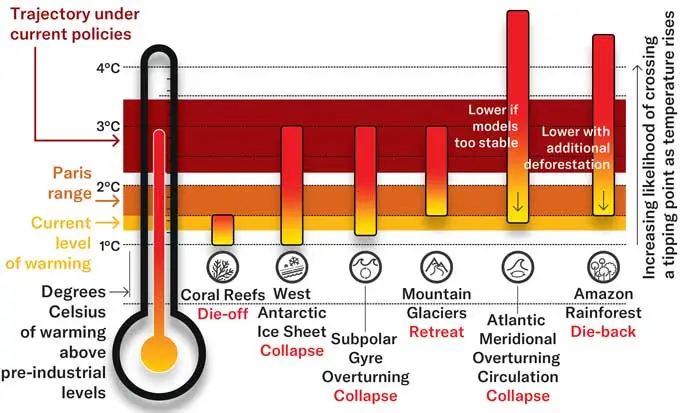

Those tipping points are points of no return, nudging the world over a proverbial peak into a new climate paradigm that, in turn, triggers a cascade of effects. Depending on the degree of warming over the next decades, the world could witness widespread dieback of the Amazon rainforest, the collapse of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets and — most worrisome of all — the collapse of a powerful ocean current system known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC.

Falling dominos

Global warming has already pushed coral reefs past their resilience limit, researchers say. Under current climate policies, warming is likely to reach about 3 degrees Celsius within decades, triggering a tipping point for collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, retreat of mountain glaciers and the collapse of an ocean current off Greenland called the subpolar gyre. The fate of the Amazon rainforest is tied both to warming and to rates of deforestation, while the fate of Atlantic ocean circulation remains uncertain under current warming trajectories. This graphic shows warming thresholds for different aspects of the climate system; past these thresholds, each system will shift dramatically into a new climate paradigm.

It is now 10 years after the historic Paris Agreement, in which nearly all of the world’s nations agreed to curb greenhouse gas emissions enough to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius by the year 2100 — preferably limiting warming to no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, in order to forestall many of the worst impacts of climate change.

But “we are seeing the backsliding of climate and environmental commitments from governments, and indeed from businesses as well,” when it comes to reducing emissions, said Tanya Steele, CEO of the United Kingdom office of the World Wildlife Fund, which hosted the press event.

The report is the second tipping point assessment released by an international consortium of over 200 researchers from more than 25 institutions. The release of the new report is intentionally timed: On October 13, ministers from nations around the world will arrive in Belém, Brazil, to begin negotiations ahead of COP30, the annual United Nations Climate Change Conference.

In 2024, there were about 150 unprecedented extreme weather events, including the worst-ever drought in the Amazon. That the conference is being held near the heart of the rainforest is an opportunity to raise awareness about that looming tipping point, Smith said. Recent analyses suggest the rainforest “is at greater risk of widespread dieback than previously thought.”

That’s because it’s not just warming that threatens the forest: It’s the combination of deforestation and climate change. Just 22 percent deforestation in the Amazon is enough to lower the tipping point threshold temperature to 1.5 degrees warming, the report states. Right now, Amazon deforestation stands at about 17 percent.

There is a glimmer of good news, Smith said. “On the plus side, we’ve also passed at least one major positive tipping point in the energy system.” Positive tipping points, he said, are paradigm shifts that trigger a cascade of positive changes. “Since 2023, we’ve witnessed rapid progress in the uptake of clean technologies worldwide,” particularly electric vehicles and solar photovoltaic, or solar cell, technology. Meanwhile, battery prices for these technologies are also dropping, and these effects “are starting to reinforce each other,” Smith said.

Still, at this point, the challenge is not about just reducing emissions or even pulling carbon out of the atmosphere, says report coauthor Manjana Milkoreit, a political scientist at the University of Oslo who researches Earth system governance.

What’s needed is a wholescale paradigm shift in how governments approach climate change and mitigations, Milkoreit and others write. The problem is that current systems of governance, national policies, rules and multinational agreements — including the Paris Agreement — were simply not designed with tipping points in mind. These systems were designed to encompass gradual, linear changes, not abrupt, rapidly cascading fallout on multiple fronts at once.

“What we’re arguing in the report is that these tipping processes really present a new kind of threat,” one that is so big it’s difficult to comprehend its scale, Milkoreit says.

The report outlines several steps that decision-makers will need to take, and soon, to avoid passing more tipping points. Cutting emissions of short-lived pollutions such as methane and black carbon are the first line of action, to buy time. The world also needs to swiftly amp up efforts for large-scale removal of carbon from the atmosphere. At both the governmental and the personal level, efforts should ramp up making global supply chains sustainable, such as by reducing demand for and consumption of products linked to deforestation.

And governments will quickly need to develop mitigation strategies to deal with multiple climate impacts at once. This isn’t a menu of choices, the report emphasizes: It’s a list of the actions that are needed.

Making these leaps amounts to a huge task, Milkoreit acknowledges. “We’re bringing this big new message, saying, ‘What you have is not good enough.’ We are well aware that this is coming within the context of 40 years of efforts and struggles, and there are lots of political dimensions, and that the climate work itself is not getting easier. The researchers struggle with this, journalists struggle with selling the terrible news and decision-makers equally have resistance to this.”

It’s important not to look away. She and her coauthors hope this report will prompt people to engage with the issue, to consider even as individuals what actions we can take now to support these efforts, whether it’s making different consumer choices or amplifying the message that the time to act is now, she says. “Even for a reader to have the courage to stay with the trouble is work, and I want to recognize that work.”