SUNKEN CITY Almost 200 nations have agreed to curb their greenhouse emissions in an effort to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius. Even with such ambitious cuts, island nations such as the Maldives, its capital Malé shown, worry that sea level rise will swallow up large portions of their land.

Timo Newton-Syms/Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Following late-night negotiations and years of anticipation, delegates from 195 countries have agreed to curb the worst effects of climate change by limiting warming to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius. The agreement, the result of an international climate summit outside Paris and approved December 12, aims to be the world’s roadmap to kicking the fossil fuel habit, with a possibility of an even more ambitious 1.5-degree goal in the future.

Even with the agreement in hand, political obstacles and technological challenges remain to reining in global warming. Individual countries will have to swap greenhouse gas‒emitting energy sources like coal, oil and natural gas for low-emission sources such as wind, solar and nuclear power. Along with yet-to-be-realized technologies that pull greenhouse gases from the air, these changes are meant to reduce net carbon emissions to zero in the second half of the century. By 2020, countries will release their long-term plans to cut emissions. Every five years, countries will reassess their progress and tweak their carbon-cutting goals.

For developed countries, the plan is to reverse the rise in carbon emissions as soon as possible. Developing countries such Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Rwanda get more leeway on when they have to start cutting back carbon emissions. They also will get help: technological support and a $100-billion-a-year fund provided by developed countries by 2020.

“It took hard work, grit and guts, but countries have finally united around a historic agreement that marks a turning point on the climate crisis,” says Jennifer Morgan, a climate policy expert with the World Resources Institute, a research organization in Washington, D.C. “The agreement is both ambitious and powered by the voices of the most vulnerable.”

Story continues below graph

Paths forward

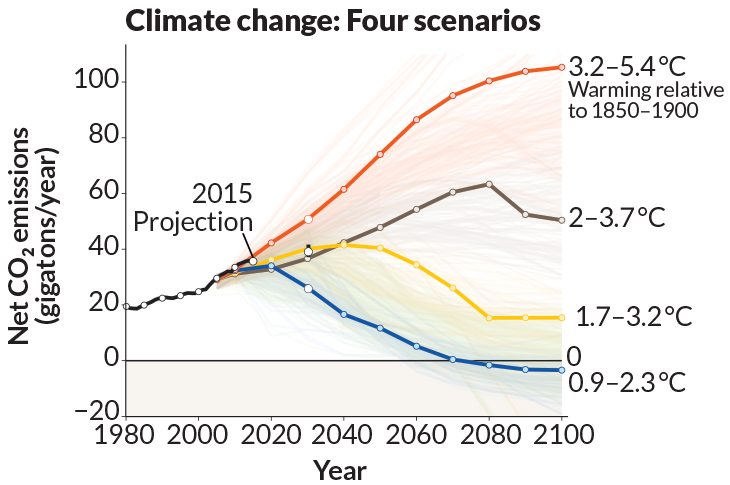

Most future carbon dioxide emission scenarios (four shown) will raise global temperatures by several degrees Celsius. A deal brokered at the Paris climate talks aims to keep warming below 2 degrees compared with preindustrial levels, a goal that requires carbon storage and capture strategies that will offset CO₂ production enough to eventually bring net carbon emissions to less than zero.

Past international efforts to combat climate change, such as the 1997 Kyoto Protocol and the 2009 Copenhagen Summit, fell short. But experts viewed this year’s Paris talks as more promising. This time around, both China and the United States, the world’s two biggest carbon emitters, showed newfound interest in striking an agreement to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

The agreement comes at a time when many experts warn that humankind is running out of time to avoid severe climate impacts. Over the last few decades, human activities such as fossil fuel burning have spiked the concentration of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide concentrations have risen from about 280 parts per million in 1880 to 400 ppm earlier this year. That rise has helped boost the planet’s average annual temperature by about one degree, with faster warming taking place over land and in the Arctic.

The Paris talks, more formally known as the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference, were held in response to warnings that a continued rise in greenhouse gases will raise Earth’s thermostat further: Business-as-usual climate simulations predict several degrees of additional warming by 2100. That warming would exacerbate droughts in parts of the world (SN: 3/7/15, p. 10), boost the intensity of strong storms (SN Online: 5/29/15) and raise global sea levels, worsening coastal flooding and drowning low-lying islands (SN Online: 9/27/13). In May, scientists also warned that unabated climate change would threaten one in six species with extinction (SN Online: 4/30/15).

The two-degree line in the sand at the heart of the newly proposed climate plan is somewhat arbitrary — scientists don’t expect an abrupt jump in disasters once that threshold is crossed. Still, as temperatures rise, the effects of climate change will increase rapidly, says Penn State glaciologist Richard Alley.

“Each degree of warming costs more than the previous one,” Alley says. One degree of warming is largely within the natural variability of Earth’s climate for most places, but once you get to two degrees, “you start to move outside of familiar territory.”

Many delegates at the Paris climate talks supported an even more ambitious target: a 1.5-degree limit to warming this century. Small island nations such as the Maldives and the Marshall Islands argued that two degrees of warming could raise sea levels enough to literally wipe swaths of their countries off the map. The 1.5-degree goal was also supported by African nations such as Sudan and Angola that are particularly vulnerable to the droughts and extreme heat that climate change intensifies. The deal invites the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to put together a special report in 2018 exploring the impact of global warming of 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

China’s delegates opposed the 1.5-degree proposal as a potentially unobtainable objective, though. Going into the talks, some experts worried that China would derail any hopes of an aggressive plan to reduce global carbon emissions. The country is in a unique situation, releasing more than a quarter of the world’s carbon emissions while also trying to support a growing and evolving economy.

Coal-fired power plants and other carbon emitters have dangerously polluted China’s air. On December 8, Beijing ground to a halt after the city’s government issued the country’s first red alert for pollution, closing schools and factories. The country has recently started investing heavily in low emission energy sources such as wind, solar and nuclear power, but the country is “doing it for health reasons, not just because they want to be good global citizens,” says MIT atmospheric scientist Kerry Emanuel.

Regardless of the country’s motivations, China’s sizable investments in low-emission energy sources have made an impact. The Global Carbon Project reported December 7 that the world’s carbon footprint shrank by about 0.6 percent in 2015, in large part due to China’s efforts (SN Online: 12/8/15). If confirmed, that reduction in global emissions will be the first ever during a period of economic growth.

At times, there’s not enough sunshine or wind, requiring a backup energy source. Worldwide, about 80 percent of that always-available energy is supplied by fossil fuels, Emanuel says, with around 20 percent from nuclear power. “If we’re going to reach this climate goal, not only do we have to build up renewables, but we also have to build nuclear power plants as fast as we can,” Emanuel says. He predicts that Germany in particular will struggle to meet its emissions targets, as the country recently started the process of decommissioning all of its nuclear power plants.

Even with the climate deal in place, the world isn’t completely out of hot water yet. Individual countries will each have to figure out how they’ll reduce carbon emissions, which can pose a challenge in places such as the United States. The country was a signatory to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, but the agreement got mired in politics and was never ratified by Congress. This time around, congressional Republicans have signaled that they’ll similarly block the implementation of the newly penned climate deal by denying funding.

“Let me be very clear — this Congress will not approve a cent of appropriations for the Green Climate Fund,” said U.S. Sen. Jim Inhofe of Oklahoma, chairman of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works.

Despite the political and technological hurdles ahead, the world is now on a safer path, says Andrew Steer, president of the World Resources Institute. “The shift from commitment into action will be even harder and take even more determination. But for today at least, we rest a little easier knowing that the world will be stronger and safer for our children and future generations.”

Editor’s Note: This story was updated December 23, 2015, to clarify the graphic on how levels of future net CO2 emissions will impact warming.