In 2017, a 5.4-magnitude earthquake rattled Pohang, South Korea, and caused widespread damage. The temblor was later linked to geothermal projects in the region.

Sim1992/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

This is a human-written story voiced by AI. Got feedback? Take our survey . (See our AI policy here .)

On August 16, 2012, residents of the tiny Dutch village of Huizinge were rattled by an inexplicably large 3.6 magnitude earthquake. Gas extraction in the nearby Groningen gas field, one of the largest onshore gas fields in the world, was the trigger. The area typically does not experience natural earthquakes, and this was the worst induced quake to hit the Netherlands to date.

Places like Groningen, India’s Deccan Plateau and Oklahoma are tectonically stable. They don’t sit at the quake-prone boundaries of tectonic plates. What fault lines they do have lie only a few kilometers below the surface, too shallow to trigger significant natural shakes. Even if the rocks along such faults had slipped millions of years ago, they have since healed, building stronger bonds across these shallow fractures.

Yet human activities — such as mining, oil and gas extraction, dam-building and tapping into geothermal energy — have set off unexpected quakes in these stable regions.

“Normally, what we think — based on textbook earthquake physics — is that if the faults get stronger, you should not be able to start an earthquake,” says earthquake physicist Ylona van Dinther of Utrecht University in the Netherlands. “But we were seeing earthquakes in Groningen, a lot.” The 2012 temblor pushed authorities to eventually stop extracting gas from that field.

Turns out that stationary, healing faults are vulnerable to human intervention. Such faults store strength over millennia of inactivity, and human activities can then push them over the edge, releasing that built-up strength in one go, van Dinther and her colleagues report October 15 in Nature Communications.

A few years ago, van Dinther’s colleagues examined the rocks lying below the Groningen gas field and discovered that the underlying faults were of a type that become stronger after tectonic movement. Unlike some deeper faults that lie at tectonic plate edges, the longer that rocks on either side of these stable faults spend in proximity without slipping, the more the area of contact increases between them.

“In the Netherlands, these faults haven’t moved for millions of years,” van Dinther says. “As they get stuck together, they get stronger. We call that frictional healing.”

If two tectonic plates try to move past each other but the fault between them is stuck, stresses start building up at that fault. Ultimately, the rocks on either side of the fault “slip” to relieve the building stress, triggering an earthquake. Stable “intra-plate” faults, in contrast, aren’t on a major plate boundary, so they don’t get jostled by moving plates. But they can suffer other stresses.

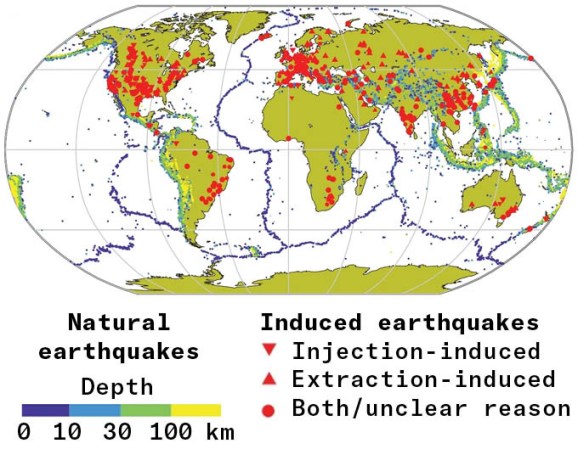

Shake map

This world map shows where natural and human-induced earthquakes occur. The natural quakes (magnitude 5 and higher) are color-coded by depth, revealing clear patterns along major tectonic plate boundaries. The red markers highlight quakes linked to human activities — such as oil and gas extraction, fluid injection and geothermal energy development. Their scattered distribution across typically quiet regions far from plate boundaries underscores how industrial activity can trigger shaking in areas not usually seen as prone to earthquakes.

Distribution of natural and induced earthquakes

For the new study, van Dinther and her team used computer simulations to investigate what happens when intra-plate faults heal undisturbed for millions of years and then suddenly experience a disturbance akin to gas extraction. This stresses the faults, and after about 35 years, the rising stress breaches the additional “frictional healing” strength. At this point, all that extra “healed” strength is released abruptly from the fault, causing a larger-than-expected drop in the built-up stress and setting off an induced earthquake.

On the plus side, once the strength is released, the fault becomes silent, and the chance of another earthquake at that fault is very low, the team observed, because it would take many millions of years for the fault to rebuild all that strength. But with more than a thousand healing faults in stable regions, human activity could trigger multiple tremors over time, as has happened in Groningen.

These induced earthquakes turn the shallow faults that would normally be protective against natural temblors into a one-time liability. The faults’ proximity to the surface can end up releasing more energy at the surface, hence shaking the ground significantly. Infrastructure in such conventionally stable regions is not built to withstand tremors.

Stakeholders looking to develop projects in such areas must understand the underlying faults and the risks they pose, says geophysicist Daniel Faulkner of the University of Liverpool in England, who was not involved with the study. Even if companies eventually move away from extracting oil and gas, they will still need Earth’s surface for clean, renewable resources such as geothermal energy. “A lot of the geothermal projects around the globe have been stopped by [induced] seismicity,” Faulkner says. In 2017, a devastating earthquake struck Pohang, South Korea, because of a nearby geothermal project, which authorities subsequently shut down.

van Dinther says that companies should try to extract resources in ways that trigger a slow movement along the faults, as opposed to a fast release of pent-up strength. This could involve carefully controlling the rate and volume of fluid injected into the Earth to harness geothermal energy, either by starting slowly and ramping up gradually or by injecting fluid cyclically.

Nevertheless, she says, developers should be aware and communicate to others in the region that an earthquake could happen. “We should account for the effect of healing and strengthening in hazard assessment.”