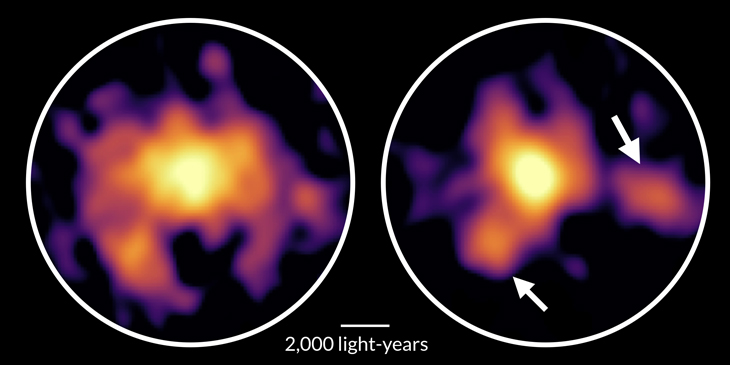

New images reveal how an ancient monster galaxy fueled furious star formation

Systems like this cranked out new stars about 1,000 times as fast as the Milky Way does

STAR-FORMING FRENZY Observations of the ancient starburst galaxy COSMOS-AzTEC-1 (artist’s impression above) help explain its startling rate of star formation.

National Astronomical Observatory of Japan