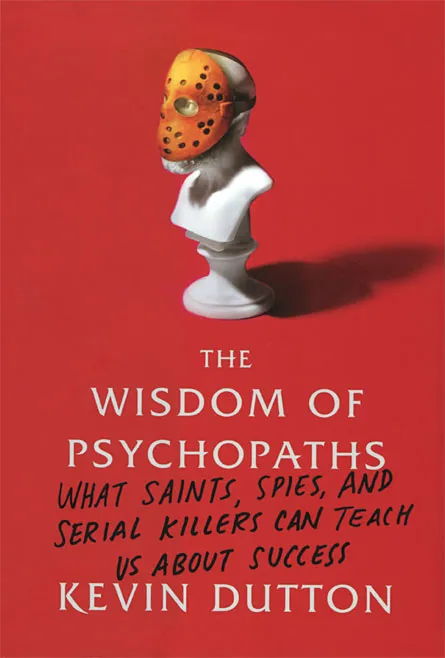

Book Review: The Wisdom of Psychopaths: What Saints, Spies, and Serial Killers Can Teach Us About Success by Kevin Dutton

Review by Allison Bohac

“My father was a psychopath,” Dutton admits in his introduction. Never violent, Dutton’s dad was charming, ruthless and fearless. He wasn’t Hannibal Lecter, just a very good salesman.

Dutton, a research psychologist, believes that his father’s case is not unique. Recent studies are blurring the lines between the psychopath and the average person. The disorder, it turns out, is more of a spectrum than an all-or-nothing state, and not all psychopaths are criminals.

In fact, Dutton argues, some of the traits that make the Ted Bundys of the world horrifying — charisma, emotional detachment and the ability to focus under pressure — could give top neurosurgeons their edge, or bomb disposal personnel their steady hands and steely nerves. The most successful politicians, CEOs, soldiers and even journalists seem to benefit from a little psychopathic edge.

To support this idea, Dutton digs into research about what the psychopathic brain does — or doesn’t do — when confronted with mental tests and moral conundrums. He interviews psychopaths, both in psychiatric hospitals and in white-collar jobs, and the neurologists who study them.

Dutton deftly navigates through some disturbing subject matter, but his message is ultimately upbeat: Scientists may be able to learn a lot from the darker side of human nature.

Scientific American/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012, 261 p., $26